A few months ago, paramedics were on the brink of industrial action. They had legitimate grievances. Ambulance services were being run down, their staffing levels were dangerously thin — and the mismanagement (much of it exposed by Mary Wakefield in The Spectator) was horrendous. But in the end they stepped back from the brink — for good reason. It went against their nature to endanger lives, and in addition it would have been a tactical mistake. If a single patient died as a result of the strike, paramedics would have lost public sympathy. Should a nationalised health service really use the unwell as a bargaining chip?

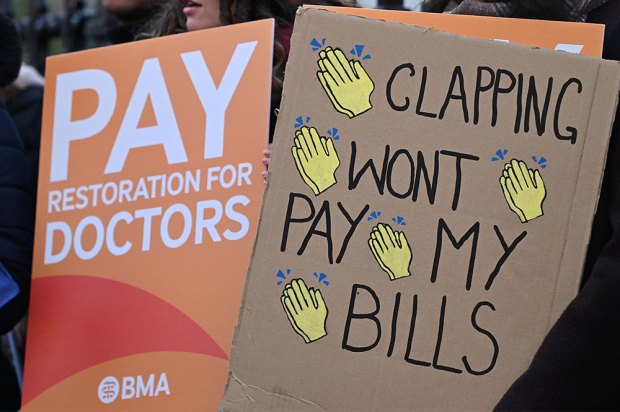

English doctors have not shown the same strategic foresight. They cancelled 3,000 operations on Wednesday because of a dispute over pay, saying they would give only emergency care. At least some of those cancelled operations will have serious consequences, as the doctors well know. In the long term, everyone who depends on the NHS will feel a little less safe and doctors look as if they are holding a nation to ransom.

The doctors have good reason to be upset. Their new contract has been handled badly by a government that has at times looked almost as if it was inviting confrontation. Jeremy Hunt, the Health Secretary, has made his case badly, placing too much weight on a controversial study suggesting that patients receive worse care at weekends. But the British Medical Association’s argument has sometimes bordered on outright deceit. It published a fake pay calculator on its website, wrongly suggesting that doctors’ pay would go down. It claims it is worried about patient safety: the blunt truth is that it is worried about money. The BMA is organising an NHS-wide strike because it can, taking advantage of the fact that the NHS is a massive, monolithic bureaucracy to impose a nationwide stoppage. The NHS is one of the largest organisations in the world behind the Chinese army and the Indian railway system. If it were liberalised, and hospitals were free to hire doctors on their own terms and conditions, the country could not be held to ransom. The strike is a reminder that keeping the NHS in its present form is a liability.

There does need to be a discussion about money. At present, those who train to be doctors in Britain are given generous subsidies by the government — more than trainee doctors in Australia or Canada. For decades, there has been an unspoken deal: in return for such generous taxpayer support during their training, junior doctors will work for lower pay than they might other-wise be offered. Certainly they earn less than in countries like Australia and the US, where the deal is that doctors take on far more student debt, which they can then repay with their higher wages.

In recent years, a new trend has been emerging: British doctors take the training subsidy offered here, then leg it to Australia for better pay. On an episode of BBC Question Time, a young doctor in the audience made precisely that point: if the UK wasn’t going to pay her properly, she said, she’d go to a country that would. She expected applause, but the audience turned on her. This response carried a warning for the BMA: yes, Britain values its doctors, but if they threaten to undermine the NHS, public sympathy falls away.

Doctors are as entitled as anyone else to pursue careers abroad. Global mobility of labour is a trademark of the 21st century, especially in healthcare. Just look at the NHS: one in four NHS doctors are foreign nationals. One in five Australian medical specialists are British, as are some 2,000 doctors in Canada. A global medical marketplace is up and running. One reason the junior doctors are striking is that they are more acutely aware of how much more money they could be making abroad. But they’d be hard pushed to name another country where doctors are given so much taxpayer support while they train.

The way we fund medical training was established in a previous era. It should be reassessed in that light. We must face the fact that we’re setting up several thousand young medics for careers in other countries. So we should offer young doctors a choice: if they take the full subsidy, then they ought to sign a contract agreeing to a certain number of years of service. If they wish to reserve the right to emigrate upon graduation, they must take their debt with them.

This is one of several changes that need to be made. The unions at present have too much control over the number of nurses and doctors who train. This should end; there should be no artificial limit on the number of training places for aspiring doctors and nurses. Once trained, it would be up to them to find work, here or abroad, just as it is up to every graduate of law, engineering or computer science. The NHS is a mass importer of medical talent; our universities are a mass exporter of talent. It is time for a funding -system that properly acknowledges that fact.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in