Paul Minx ventures boldly into Tennessee Williams country with The Long Road South. It’s 1965 and the Price family are idling about at home in Indiana. In mid-August the air is heavy with frustrated sexuality. Carol Ann Price (Imogen Stubbs) is a kindly, buxom waster slithering decorously into alcoholic dereliction. Her daughter, Ivy, is a perky little menace who cavorts about the lawn in a skimpy bikini trying to elicit male attention. Jake, the patriarch, is a charmless redneck with anger problems and a secret backlog of unpaid debt. Waiting on these white-trash parasites are two black servants, Andre and Grace, who are smart, industrious, even-tempered and limitlessly patient. Andre is a gifted theologian who pines after his severely disabled daughter. Grace is an ambitious author from New York who scribbles away at her latest novel while doubling as the Prices’ maidservant.

Even more remarkable is the distribution of ethnic prejudice in this household. The Prices are affected by the full spectrum of racial intolerance but Grace and Andre address not a single word of anti-white hostility towards their crass employers. Is this unbelievable? Andre even convinces himself that the Prices regard him as a family member even though he’s required to drink water from a separate cup. When he asks Jake for his wages, the money is thrown at him in small coins, which bounce off his proud and unbending torso and fall to earth around his noble feet. The author seems to be treating his characters differently according to the colour of their skin. Dramatically, the plan misfires because the vividly flawed Prices are much easier to like than the high-minded Andre or the pompous Grace.

The taste for this sort of retro-drama in which antique bigotries are presented for the titillation of modern audiences began with the TV soap Mad Men. Every male character was a chain-smoking bottom-pincher with blatantly sexist and anti-Semitic views. The unexamined premise was that the prejudices of the 1960s were extinct and therefore safe to be publicly aired. And yet the desire to incarnate and inspect them afresh suggests that they retained some of their allure. The get-out clause is that the viewer today watches with a detached and sophisticated eye. But I wonder. There’s a difference between being prejudiced and being a connoisseur, or archivist, of prejudice but it’s an uncomfortable line to draw.

This Will End Badly starts badly. A lone urban male tethered to the loo in his one-bedroom flat bemoans the disappearance of his girlfriend. Her departure has triggered a loss of cloacal control. But once he moves away from constipation, he becomes darkly and grippingly entertaining. Suicidal thoughts obsess him. The worst feeling in the world, he says, is to wake up knowing that you tried to end your life and failed. ‘Don’t do it,’ he counsels. Only one in 25 attempts ends successfully in death.

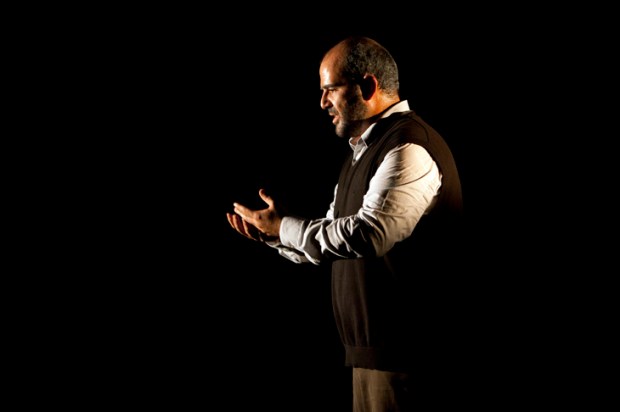

Ben Whybrow in This Will End Badly (Photo: Ben Broomfield)

Ben Whybrow in This Will End Badly (Photo: Ben Broomfield)

The rapid-fire script broadens out into a trio of voices, Misery Guts, Meat Cute and This Pain. Brutal and accurate reflections on male sexuality pile up. Meat Cute, a womanising prowler, reveals that men fetishise particular regions of the female anatomy (ankles, calves, necks, collar bones) and that they obsessively court women who bear these corporeal quirks without ever sharing the secret with the chatelaine of the erotic landmark. This is true. Less convincing is his belief that today’s sexual practices are influenced by internet porn, which gives them an indelible tincture of hatred and misogyny. Men, he claims, force their reluctant womenfolk to enact scenarios of submission learned online. And the females meekly comply with instructions from their betters. Well hardly. Romantic love could never be the slave of internet porn. And no woman would tolerate, let alone encourage, a boyfriend who plainly despised females in general and herself in particular. ‘Darling, I love the way you loathe me. Let’s get married and live hatefully ever after.’

Aside from that blip, the show is a stark and dazzling examination of the tortured male soul, and it has so much eloquent potency that the writer, Rob Hayes, must wonder why it hasn’t leapt immediately into the realm of international popularity. Well, it’s not a perfect night out. A monologue is tougher for an audience than a proper play. The focus is rather narrow, and the characters, for all their sweeping rhetoric and powers of observation, are short of humour, softness or warmth. And the structure is unsatisfying. The show ends suddenly, in mid-sentence, with a big flash of explosives where a note of measured artistic resolution would be better.

Ben Whybrow gives a virtuoso display in the three roles. The show runs for just over an hour but the script would consume 150 minutes of stage-time if enacted at newsreader speed. It’s a monumental feat of memory and performance by a sensational talent.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in