The geological title of this unhappy memoir is an apt metaphor for fissures in the relationships between individuals of David Pryce-Jones’s extended family. Emotionally and financially competitive but interdependent, benefactors and beneficiaries, Jews and gentiles of various sexual proclivities are depicted grinding away against each other like so many incompatible tectonic plates.

Pryce-Jones offers a candid expression of filial impiety for which Eton, Oxford and the Brigade of Guards surely cannot be entirely to blame, although it is true that education far from home, from an early age, has been known to piss children off, as they say. Young boys banished to boarding school may feel tormented by Oedipal yearnings and resentment of paternal indifference. David portrays his father, the late Alan Pryce-Jones, as a distinguished litterateur, a handsome, charming, talented, sociable, parasitical homosexual who, from time to time, played the part of a heterosexual for the sake of domestic convenience.

David was born in Vienna in 1936. In his early childhood his parents delegated his care to servants. In the second world war it was his devoted nanny who guided him from France via Morocco and Portugal to safety. He inherited his father’s shrewd grasp of the literary and journalistic establishments and the social hierarchies of England and the continent. Their Welsh heritage seemed to fade.

David’s first novel, Owls and Satyrs, simultaneously disguises and reveals his perception of his father’s nature. ‘In this comedy of manners,’ he explains, ‘the main character is Alan, represented as a woman too preoccupied to pay attention to others. I did not want to hurt his feelings, and this fiction was the way to come to terms.’

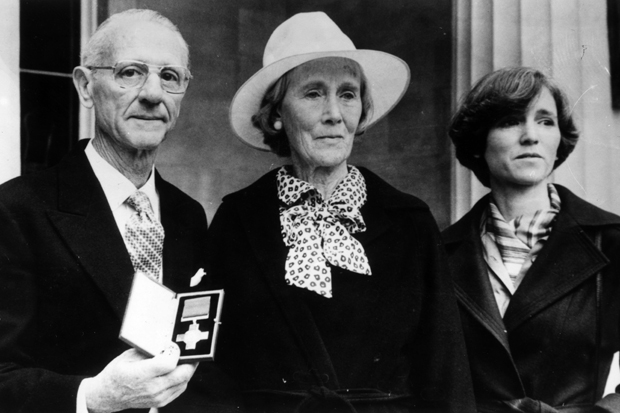

The Fould-Springer family tree, the genealogy since the mid-19th century of a European Jewish family of great wealth and influence, diagrams the framework of the society that David shows riven by materialism and snobbishness. The grandest of its dames was Mitzi Springer (1886–1978), who dominated, or attempted to dominate, her children and grandchildren by awarding or withholding large sums of money. Presumably, love and loyalty were sometimes motivating factors, but David writes best when writing of behaviour at its worst.

Mitzi lived by her motto, ‘Unite the Impossible’. Having married Eugene Fould, she declared that ‘Homosexuals make the best husbands,’ and welcomed his English lover, Frank Wooster, into a ménage à trois. He told her he was attracted to her by a spiritual affinity so strong that when Eugene died she was encouraged to become Mrs Wooster, assume British nationality and convert to Christianity.

As an undergraduate, David disapproved of Oxford as disturbingly left-wing. He dismisses Maurice Bowra’s ‘salacious’ light verse as ‘excruciating drivel’. A.J.P. Taylor, David’s tutor, invited him, years afterwards, to dinner at the Ritz with Sir Oswald Mosley:

Mosley was even more conceited and unrepentant than Taylor,’ David recalls. ‘The more Mosley defended his Hitlerite past, the more Taylor fawned on him. So frustrated was his love of power that if Mosley in 1940 had become Hitler’s British Gauleiter, Taylor would have been a natural collaborator.

Maugham, Beerbohm and Berenson were all right, but Greta Garbo was dis-

appointing. She played tennis topless and was flat-chested. David presents a more upbeat portrait of Mitzi’s only son, Max, ‘the second and last Baron Fould-Springer, nominally the head of the family,’ who presided for a while over Royaumont, a splendid château near Chantilly. He also served as the host of shooting parties at Kapuvar, an estate inherited in Hungary.

His game book records a red-letter day there in August 1935 when he and his guests, the Duc d’Ayen, Comte de Beaumont, Comte de Maille, Comte de Montsaulnier, Prince Achille Murat and Jean de Vaugelas, shot an astonishing 6,009 partridges.

This is a book to inspire political thought.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in