I usually throw away dust jackets but Robin Lane Fox chose his for a reason. He originally encountered Augustine of Hippo in the spring of 1966, after lunch and his first taste of brandy, in frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli at San Gimigniano. The quattrocento painter showed a figure with an academic air, in a gown and cake-tin-shaped hat, sitting beneath a tall, smooth-barked fig tree in the garden of a villa, his head in one hand and the fingers of the other on some lines of script in an open book on his knee. Beside him stands a man gesturing towards him.

This scene is the heart of an intense (if extensive) study by the ancient historian and garden master of New College of a man ‘educated to write like a marvel’. The marvel he has decided to explore is St Augustine’s Confessions, a book ‘like none other before or since’, an autobiography in a way, but, as Lane Fox rightly stresses, one long prayer to God, confessing in two senses: confessing sins and testifying by praise.

The turning point of Augustine’s life, half way through Lane Fox’s book, took place in a garden in Milan around 4 August in AD 386. The details are specific. The garden was a real garden, the author insists, not a figure for the Garden of Eden, or the virginal body (as in the Song of Songs); the fig tree was just a fig tree, not a reference to the tree under which the Apostle Nathaniel prayed.

Augustine, from Africa but as Latin as you like (he never mentions camels in an African context), had just taken up an academic post in Milan. As usual he was beset by questioning: where was philosophy leading; what had the Platonists to offer; what was wrong with the Manichaeans (a rum lot, quite as rum as the Catholic Christians); should he give up sex? It was already more than a decade since he had prayed, ‘Give me chastity — but not yet.’ He was 18 then, and had just been converted (away from the pursuit of money) by reading Cicero’s dialogue, the Hortensius (now lost).

So Augustine had now taken a villa in the summer vac for a reading party. One book worried him: a collection of letters by St Paul. A visitor, Ponticianus, a fellow African and an imperial courier, picked it up from the gaming table in the drawing-room, surprised to find it unconnected with Augustine’s teaching job. His response to Augustine’s perplexity at Paul’s words on the war between the flesh and the mind was even more unsettling. He told Augustine about Antony, who’d become a celibate hermit in the desert (his life published in Latin only a decade or so earlier), and about the monastery sponsored by Augustine’s hero Ambrose, here outside the walls of Milan. It was all news to Augustine.

A clump of stories about contemporaries’ conversions precedes a scene that — in Lane Fox’s judgment — is Augustine’s ‘masterpiece of self-awareness’. (Augustine anatomises his behaviour throughout life with such a sharp novelist’s scalpel as to make redundant the fashionable search for the emergence of individuality in the early modern period.) He was so overwhelmed by shame at his decade of shirking a decision on abandoning his career and illicit sex to become God’s servant that he rushed into the garden, throwing himself down beneath the fig tree in tears. It is then he heard aloud the words ‘Tolle lege’.

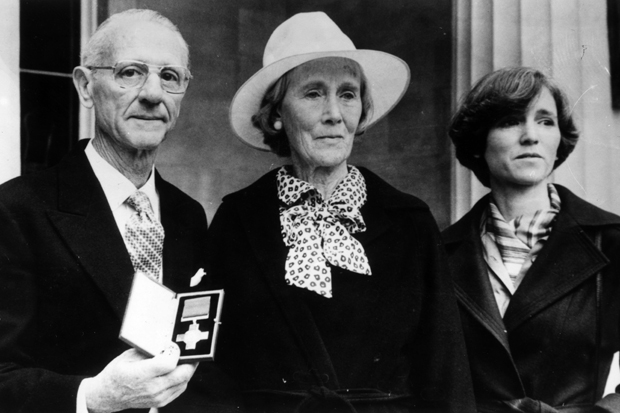

Perhaps it was a child playing a game. The words could mean ‘Pick up, gather’, as in harvesting fruit, or ‘Pick up, read’. Augustine picked up his disregarded book, witnessed by his friend Alypius, as in Gozzoli’s picture, and opened it at the words: ‘Put on the Lord Jesus Christ and make no provision for the flesh and its lusts’ (Romans 13: 14, in Lane Fox’s translation). That was it. Augustine set about resigning his job, getting baptised and embracing celibacy. First he went back into the house to tell his formidable mother Monnica (as she is hypercorrectly spelt).

This was the last of Augustine’s restless conversions, Lane Fox contends, and it arose from ‘creative misunderstanding’. The child, he argues, did not mean ‘Pick up, read’ and St Paul did not mean everyone to give up sexual intercourse. Misunderstanding? I’m not so sure. The child had no idea of Augustine’s crisis and wasn’t even talking to him, but the words spoke to his plight. It happens all the time.

This fine, reference-strewn study is not devotional, so choose with care the aunts to give it to. It is not even a biography, but stops in 397, when the Confessions were finished in a burst of activity. Augustine had 33 years ahead as a bishop. It is like stopping a book about Newman at his conversion in 1845. Augustine would write less-read master works like The City of God and On the Trinity. His thought is amply reflected in 300 surviving letters and 400 sermons, mostly taken down by shorthand writers. I can see why Lane Fox does not want to cover this ground, but it was Augustine the theologian bishop who has been the exemplar and authority for 1600 years of Christianity since.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £25 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in