Damon Albarn and Rufus Norris present a musical version of Alice in Wonderland. A challenging enterprise even if they’d stuck to the original but they’ve fast-forwarded everything to the present day. The titular heroine, a trusting and solemn Victorian schoolgirl, has been recast as Aly, a wheedling teenage grump who loathes her mum, her dad, her comp, her teachers and her playmates. ‘I hate being me,’ she announces. And as we learn more about her we’re increasingly struck by the sagacity of this verdict. To escape her distress she downloads a game from www.wonder.land and creates a cyber-self, Alice, who goes on adventures. Hmm. A computer game. Parents have for decades been urging their zombie children to toss these time-stealers into the waste-disposal unit. ‘Read a book,’ cry the adults despairingly. ‘Learn a language. Expand your world. Visit the National!’ And the National responds with? A computer game. Beside me sat a couple of bespectacled twins, aged about 10, and their unsmiling father who took their punishment with valiant stoicism. Occasionally, I heard the grinding of Dad’s teeth.

Some of Carroll’s original motifs survive but the central narrative is an underclass soap featuring a family of emotional derelicts: Aly is a lowing outcast, her dad is a luckless gambling addict and her mum is a shouty cradle-filler overwhelmed by vomiting whelps. There’s very little integration between these thumping zeroes and the delicate, playful characters who populate Aly’s parallel world. The libretto is the work of award-winning ink-squirter Moira Buffini, who has no previous experience as a composer of verse. I salute her courage in bidding such a spirited farewell to the rhymester’s craft on her debut. Unmoved by Carroll’s whimsical elegance — ‘we called him tortoise because he taught us’ — she offers us gangsta couplets instead. ‘Sometimes I hear my stepdad shouting/Piss off to bed or you’ll get a clouting.’ Lovely, isn’t it? A small polish and it could be a lullaby.

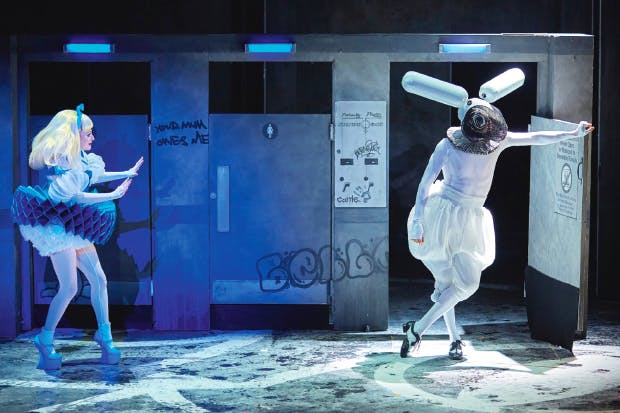

The show has redeeming features. The zingy visuals are constantly stimulating. Katrina Lindsay’s vividly overblown and highly stylised costumes created for Alice and her friends are a superb achievement. Paul Hilton exudes verve and charisma as Aly’s dad and he easily outclasses the rest of the company apart from Anna Francolini, who turns in a scene-pilfering performance as a sexy shrewish villainess. I doubt this show will succeed at the National. It’ll mystify kids and dismay parents who, perhaps misguidedly, regard the original as sacrosanct. But in a trashier cultural environment, like Las Vegas, and with a cast featuring Madonna and a disused Rolling Stone or two it could work well.

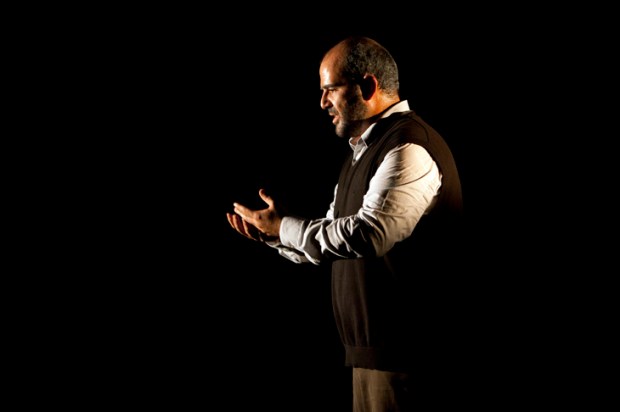

Here’s a classic Stoppardian conundrum. A spy being shadowed by an enemy agent enters a public swimming-pool. After his dip the spy goes into a locked cubicle and swaps his trunks for normal clothes. The agent can’t enter the cubicle to monitor the costume change without disclosing his presence so he must accept the incomplete evidence before him: spy enters cubicle in trunks; spy exits cubicle fully dressed. But is it the same spy? To complicate matters the spy has an identical twin.

This tableau forms the opening scene in Sir Tom Stoppard’s ingenious new thriller which embraces, among other intellectual disciplines, the puzzles of quantum mechanics. The twin in the cubicle becomes a metaphor for quantum theory, which has goaded and bemused physicists for nearly a century. Today’s boffins have yet to advance beyond the unsatisfactory conclusion that the same electron can be in two places at once. This is the only way to rationalise the unpredictable conduct of subatomic particles. And it’s a fudge. But it tastes nicer than any other fudge in the sweetshop.

The central figure in Stoppard’s play is ‘M’, a female spymaster whose son plays rugby for his public school. The touchline is an ideal place to liaise with other spies. This being Stoppard, ‘M’ has a twin sister — one of several sets of twins in the play — whose sibling is drawn into an elaborate game of double bluff. Equipped as I am with a steerage-class degree, I’m not confident that my homespun noggin was capable of grasping every twist and facet of this cerebral marvel. The ideal audience would be a theatre full of Sir Toms. Quantum theory can resolve the logistics.

Dr Seuss’s The Lorax at the Old Vic is a charming children’s show starring the excellent Simon Paisley Day. He plays a property developer confronted by the Lorax, a lovable tree sprite, who wants to halt urban expansion. The activist goblin is a tiny spherical orange puppet with a pair of Bismarck moustaches that wiggle up and down. That sounds like nothing but the effect is magical. My son, 9, called it ‘the second best play I’ve ever seen’. (It’s a musical.) ‘I could see that again,’ he added hopefully. Yeah, sorry, mate.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in