It’s the target that makes the satire as well as the satirist. Is the subject powerful, active, relevant and menacing? Patrick Barlow’s new spoof, Ben Hur, must answer ‘No’ on all four counts. The show takes aim at two principal irritants: vain actors and the Hollywood epics of the 1950s, whose titanic scale was offered as bait to audiences besotted with their cosy new TV sets. Old Hollywood is a spent ogre these days and the foibles of the acting trade are hardly a threat to civilised life, so the show can’t embrace our immediate concerns.

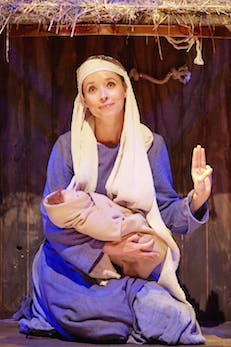

But the execution is compellingly assured. The cast is led by John Hopkins, an excellent straight actor with a fine instinct for comedy, who glides on stage as Ben Hur and dares us not to admire his strutting physique and orotund diction. The plot unfolds with a wealth of comic effects. The dialogue is written in a pastiche of Shakespearean blank verse, which might become tiresome but the satirical genre itself is toyed with and mocked. There are sight gags galore. Alix Dunmore, doubling as Esther and Tirzah, rushes off stage for costume changes that can’t be completed in time. When a centurion arrests Ben Hur, the rubber chains won’t fit over his sandals so he obligingly removes them to facilitate his enslavement. For the galley scenes, he’s shackled to an oar alongside two dolls, both clearly dead, which jerk back and forth with the ship’s oscillations. The only disappointment is the chariot race where the yoked teams of horses look very convincing without being silly or exaggerated.

Ben Hur

Audience participation is encouraged. The cast hand out cards printed with jokes to be read out by volunteers. John Hopkins, now a director, cues the lines and a scene unfolds with play-goers reciting gags that are ironically unfunny. This sort of subtle, knowing effect is typical of the show. And it won’t delight everyone. I was amazed by Ben Hur’s professionalism and yet I came away curiously drained and empty rather than tingling and fulfilled. This is a magnificent superficiality, a masterpiece of nothing. It’s like a gold-infused crouton delivered from the kitchen of the Ritz by a helicopter made of diamonds. OK. Now what?

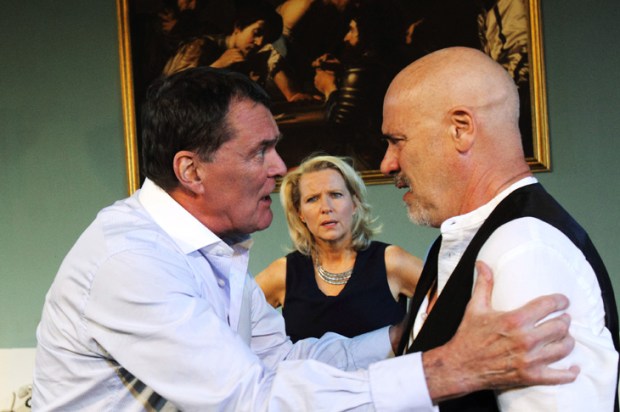

The title of Caryl Churchill’s new play, Here We Go, is an ingenious pun which may mean ‘on earth humans die’. Like this. Here (on earth) we (humans) go (die). It opens at a funeral. A charismatic celebrity has copped it and his friends recall his life in oblique snatches of disjointed dialogue. It’s enjoyable to watch but it must have been fiendish to rehearse. The characters then break the fourth wall to announce the manner of their death. Each expiry is gruesome, squalid and unpredictable. Road smash, brain tumour, lung cancer, Alzheimer’s. In this play no one lets go with an elegant roaring fade (like the end of ‘Hey Jude’). There are no gallant octogenarians bidding the world farewell while singing hymns in bed with a flask of rum and a crucifix. Death just means pain, shock and filth.

Here we go

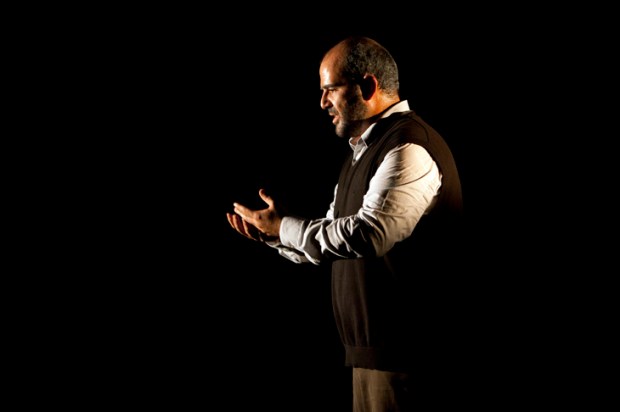

Next we get a scarily lit monologue. A half-nude pensioner (Patrick Godfrey) with a Santa beard and Hemingway chest hair barks out a ten-minute speech examining various religions and their hereafters: heaven, hell, purgatory, Hades, reincarnation. It’s like a theology lecture delivered by Captain Birdseye. Then a third scene. Captain Birdseye has moved to a hospice where a diligent, wordless carer helps him out of bed. She laboriously swaps his pyjamas for his day clothes and steers him into an armchair. Then she does it all in reverse and repeats these transitions three times in silence. The silence rings untrue. Most careworkers are positive, warm-hearted types who chat away as they perform the necessary intimacies for their patients. Mute drudgery is not their style. Could this be a libel on the nursing profession? But as the undressings went on and on (and on, for 20 minutes), I realised that this wasn’t a slice of life but an obtuse rumination on mortality, a Turner Prize entrant that got lost on its way to Tate Modern.

Pranks like this are unfair on the actors. Patrick Godfrey has to endure a near-naked performance while his partner on stage kneels with her back to the audience and tugs his undies up and down a dozen times without a word to utter. Creative professionals deserve better. We all do. The last time I was at the Lyttelton, a spectator fainted with boredom a couple of minutes before the three-hour ordeal came to an end, whereupon an NT crash team (on permanent stand-by for such emergencies, it seems) sprinted down the aisle and restored the victim to consciousness. It’s lucky this new play lasts only 40 minutes. Any longer and they’d need a field hospital on the South Bank.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in