In a drab residential street in foggy, damp Minsk, four students are at work in a squat white building that was once a garage. They vocalise sequences of letters, clap their hands, throw their arms in the air, discuss their actions. Each — three girls, one boy — is elegant, light of limb, fiercely concentrated. The room they are in is about 20 feet by 20, with two blacked-out windows and four square lights on the ceiling. It’s not certain that all the bulbs are functioning.

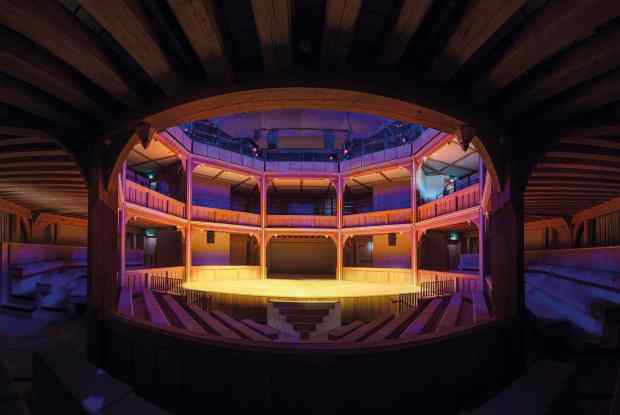

Down a tiny corridor is a bedraggled kitchen full of empty bottles that are, in fact, props. Upstairs there is a tiny rehearsal space, with a ballet-style mirror. The modest complex feels like a cross between an abandoned cricket pavilion and a bicycle shed. It is the only performing space, in Minsk, of the Belarus Free Theatre (BFT). Young Belarusians, such as these four, are lining up to take lessons there.

Performances, like rehearsals, all take place in secret. Audiences find out about them via social media. They’re contacted by mobile phone, meet outside a shop and are walked to the venue. Addresses for shows in private apartments are also texted. The procedure is being replicated in London, where the company is currently being celebrated in a festival called ‘Staging a Revolution’.

The BFT’s three co-founders, Nicolai Khalezin, his wife Natalia Kaliada and director Vladimir Shcherban, live in London. They were granted asylum in Britain after fleeing Belarus in the wake of Alexander Lukashenko’s rigged 2010 election. They campaigned to have political prisoners released. Kaliada was detained for 20 hours without water or sanitation, and threatened with rape. On a subsequent BFT visit to America, the couple appealed to the US government to place sanctions on Lukashenko — they met Hillary Clinton — and asked EU leaders to do the same. This got them branded as enemies of the state. Friends told them not to return. So the three BFT chiefs ended up in exile in the UK.

They are grimly submissive to their fate, but also full of jokes. Khalezin chuckles like a devil. The words ‘Belarus Free Theatre’ drip with irony. The company is of course the opposite of free: it is forbidden from working openly in Belarus — hence the anonymous ex-garage — and has no official funding. Being in and attending a show (always clandestinely, audiences donate what they can) are against the law.

Laws in Belarus are passed on a whim by Lukashenko’s regime. The country, long a historical punchbag, is now effectively a police state. Lukashenko secured his first election more or less fairly in 1994, but has fixed all elections since, in his favour, including the most recent one last month.

A dead ringer for Ronnie Barker’s Arkwright in Open All Hours, Lukashenko, with his Stalin-like moustache, loves ice hockey and is secretly despised by Vladimir Putin. As leaders they pretend to get along. His relations with the EU are fraught. Like North Korea’s Kim Jong-un, the president believes his land to be blessed and beyond criticism. The BFT readily criticises his security apparatus — the only one anywhere still called the KGB — and anything that smacks of hokum and prejudice. But theatrical preoccupations that for us seem normal can be treasonous in Belarus.

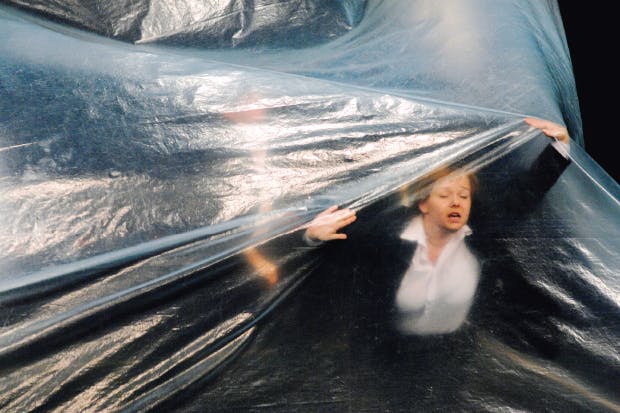

The BFT will address depression, for instance. Its first production ten years ago was a searing version of Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis, directed by Shcherban, a revival of which kicked off the London festival. Two actresses, Yana Rusakevich and Maryia Sazonava, interpret this nakedly confessional text as a consuming love affair.

When I saw it in Minsk, with 50 people watching from makeshift benches, the women roared the pain with primal intensity, but also with blistering technical control. In a scene that lists the medication the play’s patients are taking, fruit from a huge bowl became the pills, gobbled and spat out by the duo. The sheer daring of the acting throughout made this the most compelling production of any Kane play I have seen. ‘It’s completely screwed me up,’ a Belarusian woman announced after the same performance, ‘but I loved it.’

Lukashenko denies the existence of such darkness in his country. The BFT — as is normal for a gang of youngsters finding themselves through drama — explores sexual variance, and again this is problematic. One of Lukashenko’s more spectacular declarations of self-congratulation resembles Queen Victoria’s refusal to believe that women could be lesbians.‘Better to be a dictator than gay,’ he said in early 2012. These days, Lukashenko’s illegitimate 11-year-old son Kolya, reportedly sired on a pop singer and being groomed as his dad’s political successor, is regularly paraded as a mascot at public events.

Khalezin and Kaliada dreamt up the BFT in 2004. In mid-2005 they were joined by Shcherban. Together they were clever, canny and fearless. They suspected that an independent theatre troupe with edgy tastes and a provocative aesthetic would hit the buffers in Belarus. So they solicited and got pre-emptive support from Vaclav Havel, the dissident-turned-president, who detected in what the BFT was doing loud echoes of his experiences as a banned playwright in communist Czechoslovakia, and from Tom Stoppard, who remains a patron of the company. This gave it an international profile of sorts. Unsurprisingly, Lukaskenko and his cronies loathed the BFT, and proscribed it before it really began.

In a slightly riotous interview at the Young Vic, where the BFT has its office, the company’s three founders laugh about Lukashenko constantly. For exiles they are remarkably cheery. When they started out, they say, Lukashenko had been to the theatre just once in 20 years.

‘It was,’ Shcherban says, ‘kind of hard to state: “Let’s start something only to run into problems.” We began the company to move away from problems, in a way. Ten years ago Belarus was in a unique cultural situation. The government already controlled all media: TV, newspapers and magazines, everything. Theatre wasn’t controlled so much.’

But theatre was quickly controlled if you attacked or were perceived as attacking the government. The BFT had to go underground. There it has stayed. From London, the trio consult their Minsk colleagues and students, and rehearse them, on Skype.

‘The student programme is called Fortinbras,’ Kaliada says (the tribute to the only man left standing at the end of Hamlet is deliberate). ‘This is important for us. We’re lucky to have so many students, but at the same time it’s unfortunate as it won’t be possible for them to become a part of the BFT.’

So why do so many want to join this perilous enterprise?

‘We’re cool,’ Shcherban replies, quick as a flash. And they are: charismatic, fun and now invited to festivals around the world, which is largely how the BFT makes its money.

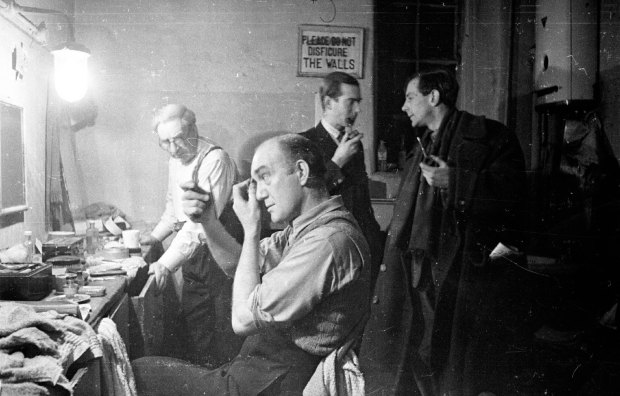

Back in Minsk, the four students are being observed by a small woman with short blonde hair, Maryna Yurevich. Along with the two actors mentioned above, she is one of 13 who perform full-time. All of this happens in secret.

Yurevich prompts the students when they fluff, then explains to me in English: ‘This is about co-ordination. They must practise, hard.’ Next, they build an obstacle course with benches and stools, which they negotiate first with their eyes open, then blindfolded. Yurevich stares at every step they take, and comments brightly, engaged in the exercise with the dedication of a seasoned BFT expert.

Which she is. The other show I saw in Minsk was Time of Women, a verbatim play by Khalezin and Kaliada about three women activist-journalists jailed in 2011 for protesting against Lukashenko’s ‘re-election’. The stage was turned into a prison cell. Yurevich, along with the two Psychosis performers, and with Kiryl Kanstantsinau playing the women’s revolting interrogator, depicted defiance and courage with gutsy naturalism. The play’s UK première is at the Young Vic on 9 November.

With its complex short history, and paradoxes of location and practice, how good is the BFT? On the evidence of what I witnessed in Minsk, not only are its performers fascinating on stage, this is one tight, rigorously disciplined, not to say very brave ship. It won’t be sailing back into Belarus, national flags there waving, arms in open welcome, any time soon. But it is getting very seriously noticed in many ports around the globe. Nothing, surely, could annoy an absurd European dictator more.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in