Provincial repertory theatre, in which a semi-permanent company of actors performed a varied diet of plays for their community, week-in, week-out, has all but died out in Britain. Local theatres have become venues for visiting productions, one-off events and numerous outreach schemes, but the old continuity – a kind of magic – has gone.

I caught the last of it as a child. I was nine years old when in 1979 the brand-new playhouse in my area – the Wolsey Theatre, Ipswich – opened its doors to the public, and for the next four years it would be the centre of my world. If I wasn’t watching shows there (and I saw some half a dozen times), I was dreaming about it, reading scripts or writing to a local photographer for black-and-white photos of the company’s players. Other boys at school knew all the details of the Premier League. I knew the XYZ of the Wolsey and its company, right down to the wardrobe mistress and the man who ran the front of house.

It was like belonging to a club, and could fill your life if you wanted it to. There were three-week runs (meaning the plays changed every month), one-off lunchtime productions and occasional special events (I even caught Quentin Crisp giving his one-man show there). By the age of 13 I’d seen works by Brecht, Rattigan, Pinter, Ayckbourn, Noël Coward, Sheridan and Shakespeare. The theatre had caught me at an age when you’re still wide-eyed and undiscriminating – in the best way – about everything you see. At interviews for senior school I sailed through, chattering away about The Caretaker, Private Lives or The Caucasian Chalk Circle. Here, far more than in the classroom, I got my education.

I loved the whole atmosphere of the place. The foyer with its soft patterned carpet, the theatre café selling scones and filter coffee, the black-and-white stills on the walls of the current production – more enticing than any film trailer. I can still remember the auditorium’s raked tiers of lime-green seats (now gone) with the donors’ names on tablets in the corridor, or, tantalisingly, the way the curtainless apron stage would give you time to study the set before the play began.

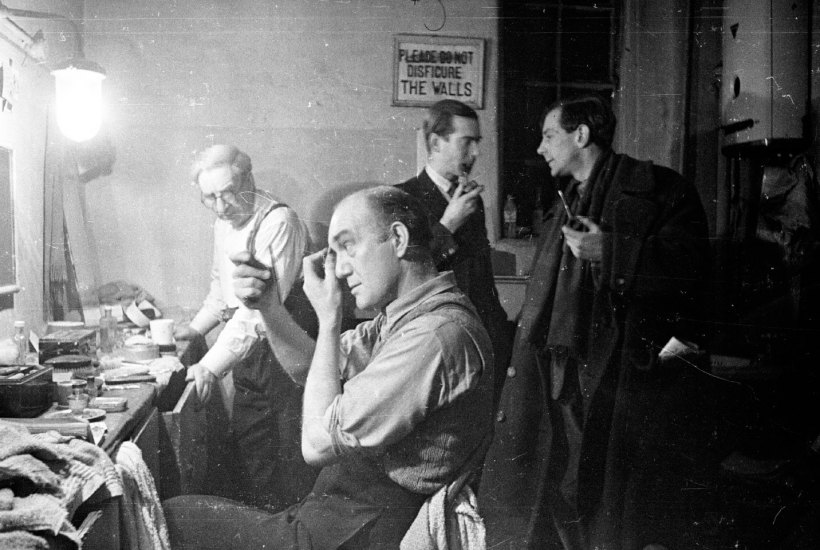

But the best thing about it was the actors. You followed them from one production to another, studied their form and stared at their portraits in the foyer. In the evenings, after the performance, they would sprawl in mufti in the upstairs bar, breaking off their flirtations to be saintly-generous to this irksome ten-year-old bothering them with an autograph book.

This was the last gasp of the old theatre before actors felt drearily impelled to present themselves as more normal and down-to-earth than the average man in the street – itself a kind of pretence. There was a kind of style, an openly rarefied quality, about these people that I loved. Chekhov once said there was nothing worse than provincial celebrities, but the very opposite, I found, was true. You remembered them like you remember great teachers at school – they were approachable and generous, and they loomed, in that tiny environment, very large.

Some of them were on their way to bigger things. Tom Mannion would have a respectable West End career and find TV fame in Emmerdale Farm. Gabrielle Glaister, wide-eyed and pouty ingénue-in-residence, the stuff of every Ipswich teenage boy’s fantasies, would go on to play ‘Young Bob’ in Blackadder.

But the Wolsey’s actor in excelsis was a man named Brian Theodore Ralph. Other actors came and went; he stayed put, and I saw him play King Arthur, Sky Masterson, Petruchio, Buckingham in Richard III and The Elephant Man’s good doctor Frederick Treves. I have seen great West End performances since then – Robert Stephens as Falstaff, Simon Russell Beale as Konstantin in The Seagull – though remember none as more thrilling than his.

Recently, I was lucky enough to find the same Brian Theodore Ralph on LinkedIn. He was, his profile told me, ‘retired and considering options’, though I found public readings he’d recently done of Dickens and Dylan Thomas. Regarding his glory days in rep, what did he remember of that lost world? He gave me his memories, in a long email.

Theodore Ralph is old enough to remember the days in rep of having to call the actors Mr or Miss unless invited to do otherwise, and of being contracted to provide your own day suits and dinner jackets. Yet it was a considerable training for a young actor. Those today, he believes, ‘are not given the opportunity to play a wide variety of roles and their voices are not exercised’. By contrast, at the Wolsey he got to direct or act in around 50 productions over the 13 years he was there, and he remembers the experience of being rooted in a smallish town as ‘idyllic… It is hard to explain how good it feels to have people regularly stop you in the street to talk about your latest performance; to be asked to visit the local hospital at Christmas time; to build up a following of so many loyal audiences, who years after still talk to you about what they, and I repeat they, refer to as “those great times”’.

He was never happier, he told me ‘than when I was working flat out rehearsing one play during the day, performing another in the evening and often performing or directing a lunch-time play simultaneously…. What more could any actor wish for?’ He remembers vividly how it all ended. ‘Slowly the number of theatres becoming receiving houses or doing joint productions with other theatres increased. With it the existence of companies of actors retained for two, three or more plays in regional theatres ceased to exist…’

The New Wolsey (rather like New Labour) has, I note from its website, battled bravely on, but with its disconnected visiting productions (many for just a couple of nights) and lack of a permanent company, it’s surely a ghost of itself. ‘For communities,’ says Theodore Ralph, ‘the recognisable and familiar faces of “their” actors ceased to appear. For actors a whole way of life has gone.’

For years, if only as a fanboy, that ‘way of life’ made up my world too. Its stars and its season of changing productions mapped out my year, and perhaps for me too it was too good to last. As I hit my teens, my older sister started renting a flat in London. There were cigarettes, LPs, older girls, blagging an underage drink in Chelsea pubs – and bigger venues to go to. Life had suddenly got wider and more urgent than this provincial playhouse that had formed me. For a while I saw the Wolsey Theatre in my rearview mirror, then it faded completely from view. It wasn’t until decades later, when the hubbub subsided, that I realised what I, and Ipswich, had been lucky enough to coincide with. It had brought stardust, a sense of belonging and a vividly varied culture into our lives.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in