Maybe what we love about radio is the way that most of its programming allows us the luxury of staying content with ourselves, of realising that it’s OK to be no more, or less, than average. There’s no spangle, no sparkle on the wireless; nothing to make us feel we should be aspiring to live in a fake and fantastical world of gilded lives, to be uber-rich, super-tanned, ultra-happy. On the contrary, you could say most radio is a celebration of Ms or Mr Average.

Think of all those short stories, plays, features and real-time, real-voice recordings which take us right inside (too far inside, some might say) the banality of most domestic situations. We can listen in our average homes, with our modest decor, glitter-free wardrobes, our everyday routines and lack of red-carpet party invitations, and take comfort from the fact that the people we are listening to are no different from ourselves.

Such thoughts were triggered by Ian Sansom’s series of essays for Radio 3, About Average (produced by Stan Ferguson). What’s wrong with being average? he asked. Why has outdoing, surpassing average become the mantra of our times?

Sansom reminded us that what was once average — the fact, for instance, that just a few decades back we all (or most of us at least) smoked like chimneys, and wore gloves, hats and three-piece suits — soon becomes exceptional, and vice versa. He quoted from W.H. Auden’s poem ‘The Average’ about a young man whose parents sacrificed everything in their desperate desire to turn their son into something special. But when he saw himself as ‘the shadow of an Average Man Attempting the Exceptional’, he could only run away. Those who despise the average, Sansom concluded, are people-haters.

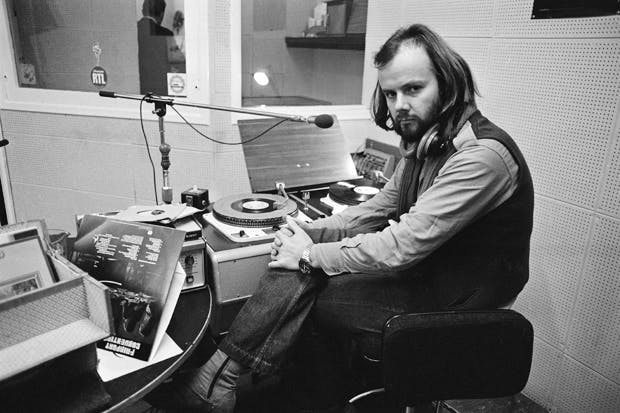

This thought, you could say, was echoed by Brian Eno on Sunday night. He was giving this year’s John Peel Lecture (BBC Radio 6 Music) in memory of the radio presenter and music buff — an oxymoron in itself, for surely Peel would never have been seen dead behind a lectern. Eno, though, with his signature obtuseness, that ability to look at things backways on (he once advised us, for instance, to ‘honour’ our mistakes and to look at them instead as ‘hidden intentions’), gave us all a surprise by delivering a philosophical/political treatise packed with literary references and fuelled by a passion not so much for music (rarely mentioning his own achievements in that field) but for education, for opening minds, for art as playtime for adults.

He began by asking that somewhat predictable question, is art a luxury? But he gave it an Eno twist by suggesting ‘art is what we don’t have to do’. We have to eat, but we don’t have to create a baked Alaska. We have to wear clothes but not necessarily Dior or Dr Martens. We have to move but we don’t have to dance a rumba. We have to communicate but we don’t have to write epic poetry. Straight away he invited us in to think about art not as a form of activity indulged in only by the lucky few, but art as something we all can (and indeed should) inhabit everyday. He also saw this as something very Reithian, very BBC in fact.

You may have heard about the letter written by the heads of seven Scandinavian broadcasting corporations in praise of the BBC or rather its role both as a democratic enabler at home and as a promoter of British interests on the international stage. Steve Hewlett, on last week’s The Media Show (Wednesday), talked to Cilla Benko, the director-general of Sweden’s publicly funded radio station, Sveriges Radio. What struck me about the interview was not Benko’s enthusiasm for the BBC, or her warning that diminishing the BBC at home would diminish Britain’s stature on the international stage, but Hewlett’s line of questioning, which was both aggressively interrogative and surprisingly defensive, as if he himself was not convinced about the BBC’s role and future.

First he seemed surprised that the Scandinavians knew all about charter renewal and the licence fee. Then he barged in, ‘Did the BBC have anything to do with the writing of this letter?’ To which Ms Benko replied, tartly, ‘This was our initiative …We are quite aware of what is going on in your country,’ wrongfooting Hewlett.

He had insulted her intelligence as a leading broadcaster (of course, she would know about how the BBC works, and especially the debate about how to fund it). He diminished the BBC by suggesting that the Scandinavian broadcasters would not have thought of writing the letter of their own volition, out of their own admiration of and concern for the corporation. And he had not given us, his listeners, the information we needed by asking the right question: why are you so concerned?

Radio 3’s weekend marathon at the Wellcome Collection in quest of answers to the question ‘Why music?’ was a timely illustration of why Benko and co. might be concerned about the future of the BBC. Max Richter’s composition Sleep, which was played through the night, secured Radio 3 a Guinness World Record for longest live broadcast of a single work. Definitely not average. But how many listeners stayed awake to hear it?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in