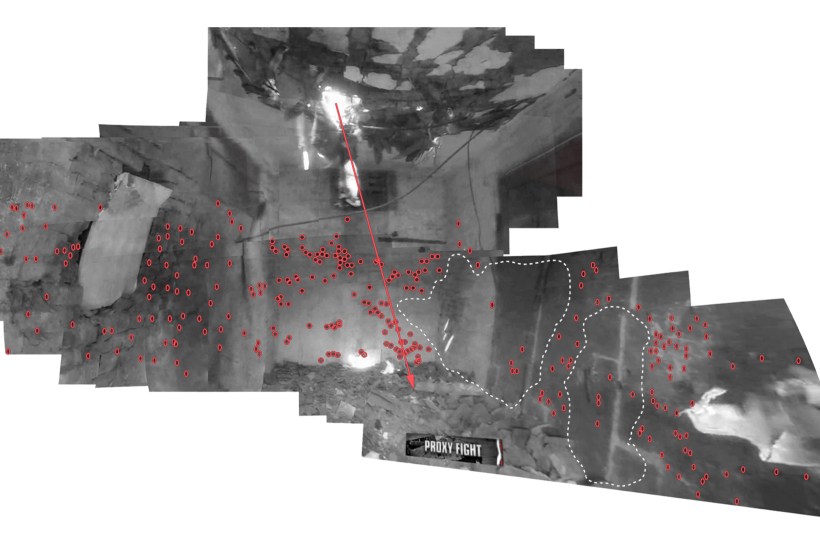

I hadn’t really thought much about pixels before, despite spending a large portion of my day looking at them. After all, a pixel is just a tiny unit in a digital image, and we all tend to look at the bigger picture. But how about this: this humble unit has now become a key feature of drone warfare. Drone-fired missiles have reportedly been developed that can burrow through targeted buildings, and leave a hole that appears smaller than a pixel on publicly available satellite images. This means that drone strikes are often invisible to groups who try to monitor attacks, such as NGOs or the UN.

As Eyal Weizman, an expert in ‘forensic architecture’, puts it: ‘One of the foundational principles of forensics since the 19th century has been inverted: to resolve a crime the police should be able to see more, use better optics, than the perpetrator of the crime. Here, it is the state agencies that do the killing and the independent organisations the forensics. The differential in visual capacity to see is the space of denial.’

I now can’t stop thinking about pixels, and it’s all thanks to a small and intriguing exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery called Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence. It sets out to examine the ability of photographic images to document violent, criminal acts, and uses 11 diverse case studies from the past 100 years to ask questions about whether photographs can ever convey objective truth.

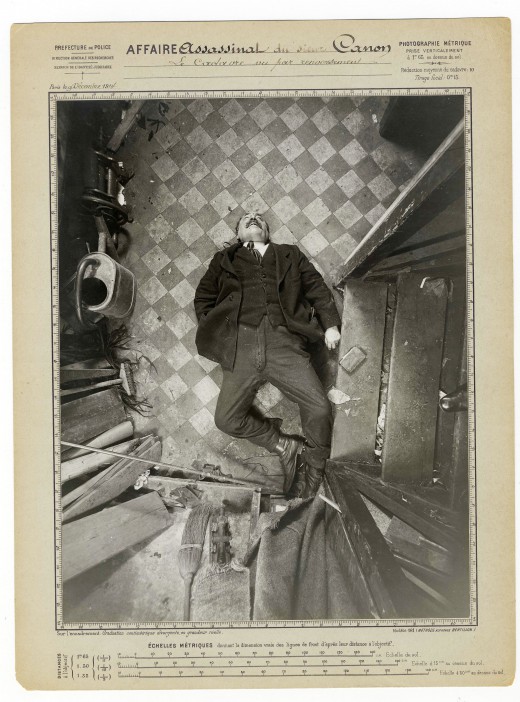

In the early 20th century, when photography was in its nascent state, it was considered an impartial technique for investigation. Alphonse Bertillon, a French police officer and biometrics researcher, developed a protocol for its use in criminal investigations, which became known as ‘metric photography’. A camera with a wide-angle lens was suspended on a tripod over the corpse, in order to establish the position within the crime scene. At the time, this was considered scientific, but to a modern eye, these images look deliciously macabre, and the way they are framed is quite attractive. They are full of tantalising details, and we are left to imagine why — and how — characters such as Monsieur Mathieu, Madame Laurent and Monsieur Delorme were bumped off.

The veracity of photography is the main theme — which is quite a broad one, to say the least — and the case studies don’t exactly join up seamlessly. One corner of this compact show is dedicated to 200 people who lost their lives during Stalin’s Great Terror. Many of those arrested during this period were tortured into confessing to crimes and conspiracies, and some were photographed in the days prior to their execution. Originally intended as a way for the executioners to confirm who had been killed, these chilling photographs now serve as damning evidence of Soviet-era state brutality.

Some of the other case studies feel more detached from the violence. Before and after aerial photographs of large-scale offensives from the second world war aren’t that revealing — or at least not to the untrained eye. At times, the show feels like a rather bitty university lecture delivered by an enthusiastic but scatterbrained professor. Plenty of interesting stuff, but it’s pretty erratic.

Images of the Turin Shroud and of Josef Mengele’s skull are also included. Both items are equally ghoulish. The shroud, which supposedly showed the ‘narrative of the passion’, is billed as the ‘first crime photograph’ — sensationalist enough — but this was all discredited in 1986, when the photographic methods used to reach this conclusion were disproved by carbon dating. The archbishop of Turin had to announce sheepishly that the shroud did not date back to Christ’s time, but instead to 1260–1390 AD. With Mengele’s skull, a videographic technique was used to determine whether a skeleton found in the suburbs of São Paulo belonged to him. As Clyde Snow, a forensic expert, puts it, ‘Bones make good witnesses. They never lie.’ It was indeed the ‘executioner of Auschwitz’.

Seen as a whole, these case studies demonstrate the paradoxical nature of photography. The camera does capture what’s put in front of it — but that doesn’t necessarily mean a photograph reveals the truth. As a forensic tool, it is fallible. And nowhere is photography more fallible than when it comes to the pixel. The photos of rotting corpses and mangled, bruised cadavers are grim to look at, and play to our modern-day obsession with graphic imagery. But perhaps more unsettling is the creeping realisation that often the real evidence now lies beyond what we can see. In the digital age, photography has become an altogether different medium. Weapons are now being used that actively exploit the limitations of what we can see.

Photography was once considered an essential tool in the justice system. But if pixels can be manipulated, and the gaps between them exploited, can we really trust the bigger picture any longer? Photography can both show and hide evidence. There lies the burden.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in