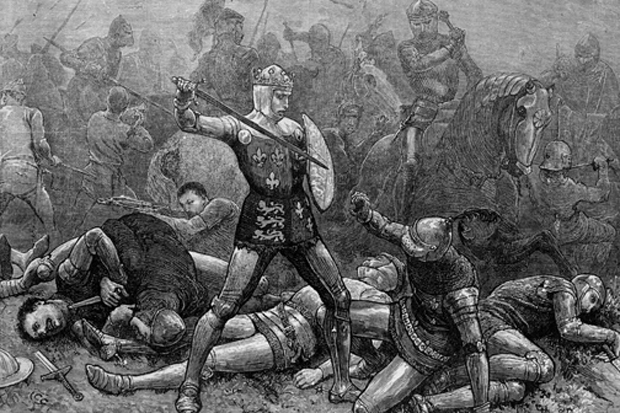

Can anyone explain this sudden enthusiasm for Agincourt, that unexpected victory over the French, now being celebrated, or rather commemorated, on radio, on digital, online? It was so weird to switch on Radio 4 on Sunday morning (which just happened to be St Crispin’s Day, the day on which the battle was fought) to discover that even Sunday Worship was being devoted to commemorating one of the bloodiest battles in that most bloodthirsty period.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in