The blackness that sweeps along the stage behind Sylvie Guillem’s disappearing figure in the Russell Maliphant piece on her farewell tour is an astonishing moment. One flinches. An eclipse has happened and the light has just run away with her. All gone. Michael Hulls’s momentous lighting states Guillem’s intentions as clearly as Elias Benxon’s filmwork in the closing piece, Mats Ek’s Bye, which shows this singular performer quitting her elite world of imagemaking and humbly, nervously, going out to join the masses in the street. After lights out, she intends there to be no legacy.

As I had hoped might happen, elements of Guillem’s closing show, unveiled at Sadler’s Wells in May, had progressed to advantage when it reappeared at the Coliseum to hoover up the queues of Londoners begging to see her in her long-adopted city for the last time.

Akram Khan’s solo for her, technê, has her scuttling less and exploring more. In the Coliseum’s broader spaces, Sylvie looked supernaturally light of foot, supremely fastidious and world-curious. The production seemed to have a personal theme now, binding the four works together: a sense of inquiry, expressed wonderingly (Khan), or amusedly (Forsythe), or serenely (Maliphant), or hopefully (Ek). And that really isn’t an empty legacy at all.

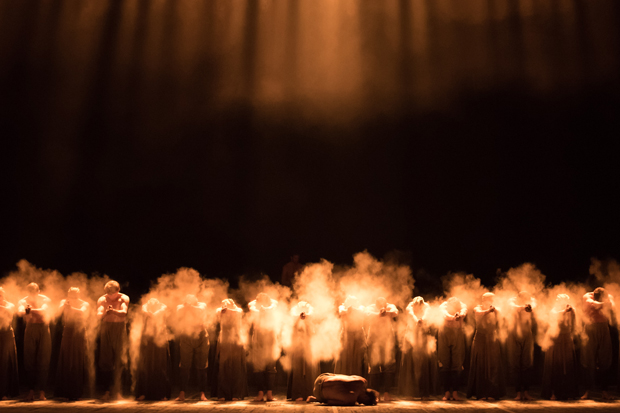

Carlos Acosta has absolutely different plans for his legacy. Now 42, the limitlessly charming Cuban superstar, who’s retiring from the Royal Ballet next year, is auditioning worldwide to launch his own troupe on his native island, and Cubanía, his self-produced show at the Royal Opera House, was also a kind of undressing for him. He is sloughing off his noble ballet togs and miraculously bouncy young grace and embracing a new contemporary habit, but I hope he doesn’t feel that he has something to apologise for.

Here he was, in Miguel Altunaga’s duet Derrumbe, apologetically slumping in a thinly choreographed, mirthlessly imagined break-up with Pieter Symonds, which has more flying shirts than steps. Here he was, in his own Tocororo Suite, apologising for being a ballet boy in streetwise Havana. To be honest, he’s too old and too great for that to come off entirely for British audiences, though he encourages the Danza Contemporanea de Cuba girls and boys to perform with infectious gusto.

The irony is that there was a tremendous, noble, intricately smooth solo in the programme, Flux by Russell Maliphant (a much better creation than his one for Guillem’s show), which provided the magnetic veteran Alexander Varona with the evening’s highlight. When you saw Varona half an hour later, in Tocororo, as a typical Cuban criminal dude, swaggering in shades and white panama hat, you saw a performer who’s succeeded in making both ends meet: slick, stock Cuban pantomime dance and top European contemporary dance.

Acosta’s salient qualities can’t take him in either of those directions. His chief blessings are that he has always been the utmost gent with his ladies and such an irresistibly sunny dynamo at the ballet party. While the show starved us rather of the party-giver, we got the super gentleman in his duet with Zenaida Yanowsky from the Royal Ballet — Edwaard Liang’s Sight Unseen, which used some delightfully mournful Georgian a cappella singing. I couldn’t call the steps amazing, but it perceptively contrasted the long-limbed, contemplative Yanowsky and her shining clarity of line with Acosta’s muscular, pantherine urgency. Watching them, you saw how powerful understatement can be.

However, for a great dancer to leave a legacy — and Acosta hopes for a very solid one — is damned tricky. Ask Peter Schaufuss, Seventies ballet star, who 30-odd years ago was hoping to pile success on lustre as he moved into directing and choreography (he led English National Ballet in exciting dance in the late 1980s).

Since then his legacy has been fatally tarnished by the appalling taste of his own creations, viz the gruesome Midnight Express, the Tchaikovsky Trilogy and the screamingly awful Diana: the Princess, in which Camilla rode Charles in her jodhpurs and smacked his bottom with her whip until he had a munch at her crotch.

More creditworthy bequests to ballet are his care with mounting works in his native Danish tradition — and his talented balletic offspring. His children Tara and Luke guest-starred last week at the Coliseum in Queensland Ballet’s well-intended performance of Schaufuss’s staging of the first Romantic ballet, La Sylphide (their audiences, sadly, were battered by the Tube strike).

Luke, 21, with first-night honours as the kilted James who is waylaid by a ghostly sylphide on the eve of his wedding, has exceptional spring and grace in his jumps, like his dad. He also carries his handsome blonde head with a dignity that should take him places (he’s presently in Birmingham Royal Ballet’s corps de ballet), though like Dad he was short on dramatic commitment. More arresting was redhead Mia Heathcote as a delightfully passionate Effie, his rejected fiancée (she, too, is balletic offspring, daughter of Australia’s star dancer Steven Heathcote).

Schaufuss père’s success in coaching a secondary Australian troupe to dance this elusive early ballet nicely and without mucking it about deserves credit — but how many people notice a legacy like that?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in