It’s one thing to make the most boring film in cinema history — at least you can kid yourself at the outset that it might turn out differently. It’s quite another to lovingly recreate the same film half a century later, shot by eye-bleeding shot, but that’s exactly what I’ve been doing, I’m proud to say. I say shot by shot, but since Andy Warhol’s Empire consists of a single locked-off shot of the Empire State Building running to 8 hours 5 minutes in black-and-white yawn-o-vision, that’s not much to write home about. Nor is the rest of the movie, from almost any popcorn-munching perspective you can think of.

With the honourable exception of this magazine’s Deborah Ross, many film critics seem to be docile, calf-like creatures, happy to live in the dark and be fed the same thing over and over again. But even they were stirred from their torpor by Empire, which regularly leaves a crowded field behind in cinéastes’ polls of the dullest films ever committed to celluloid.

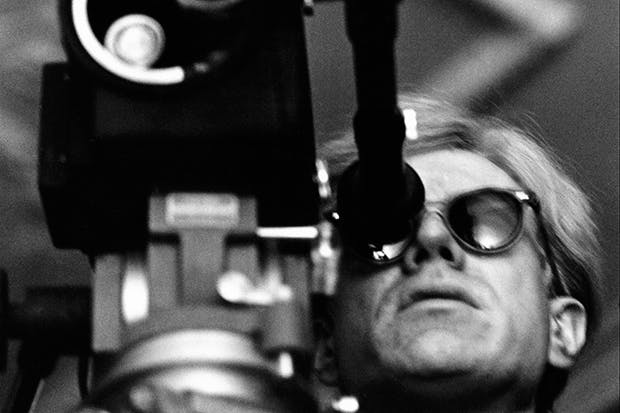

On an autumn evening in 1964, Warhol and half a dozen cronies entered the Time-Life Building in Manhattan after working hours. They ascended to an office on the 41st floor with an uninterrupted view of the titular skyscraper. They set up Warhol’s new Auricon camera on a tripod and, apart from changing the rolls of film every 35 minutes or so, that was more or less that.

On its release, Empire enjoyed the proverbial mixed reviews. Some people booed and asked for their money back. An Austrian audience sat through the whole picture with iron self-will. It emerged later that a Viennese newspaper had offered a cash prize to anyone who could stick it out.

So why go to the trouble of filming the wretched thing all over again? Well, director David Shulman and I have been trying to recreate 24 hours in Warhol’s life in the mid-1960s, and wanted some footage of the Empire State Building, though nothing like as much as he did. Warhol was that curious beast, a best-in-show publicity hound who gave the impression that he barely had the energy to wag his own tail. Despite the success of his silkscreen pictures of America’s sweethearts and favourite household products, he announced that he was retiring from painting, and was henceforth concentrating on film instead. He had saluted Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, but now he would create his own ‘superstars’, like the doe-eyed ingenue Edie Sedgwick. He idolised Hollywood and longed to be part of it, though he perhaps recognised that he lacked the necessary skills of storyboarding and editing. Much better just to set the camera rolling and await the results.

For our homage to Warhol, we weren’t going mob-handed like he did, but we did have one of his original crew with us. Gerard Malanga enjoyed a reputation as a bit of a stud at Warhol’s studio, the Factory, and he can be seen filling his boots in one of the artist’s racier pictures, Couch. Now 72, Malanga lives quietly in Hudson, upstate New York, with his four cats. He looks a little like Dennis Skinner MP and walks with a cane. He was Warhol’s majordomo and did a lot of the heavy lifting on his painting and film projects. He told me that he was surprised to see recently that a couple of Warhol’s Elvis pictures had been sold. ‘I thought, “More Elvises? I don’t remember making those.”’ Then he recalled that several silkscreens of the king of rock’n’roll had been stored in Warhol’s first New York studio and damaged by rainwater after the roof leaked. Malanga had assumed the works had all been written off.

True to the bracing lack of sentimentality with which New Yorkers regard their built environment, Warhol’s studio is no more (indeed, all the three iterations of his Factory are no more). The Time-Life Building is still there, as is the Empire State Building, but the former no longer boasts an unobstructed view of the latter.

So we paid off a janitor called Ray who looked after a high-rise block said to enjoy a fine aspect of the ESB. He could smuggle us into his building after hours on Memorial Day weekend, a public holiday. The plan was to shoot from the rooftop — which seemed to belong to Ray’s uncle. ‘If it was down to me, you guys could come and go as you please,’ Ray assured us. ‘But you see, fellas, this is a union building, and then I have to think of my uncle…’ It was worth paying handsomely for this one-man promenade performance of the Spanish customs of Old New York.

We followed Ray into the elevator, along empty corridors, up several flights of stairs and at last through a fire door and on to the roof. As Malanga caught his breath, leaning on his stick, we admired unequalled views of New York’s distinctive wooden water towers, like prototype lunar-landing modules awaiting blast-off. Of the ESB we could make out very little.

Disaster! Where were we going to get our shot now? Everywhere was shut for the holiday weekend. Someone remembered a supper club located many storeys above street level: it might just do the job, if we could blag our way in. A few minutes later, we were jinking past a crocodile of smartly dressed diners into the back room of the joint. As waiters plated up entrées, we placed our camera in front of a picture window that framed Gotham’s soaring art deco hypodermic, and settled in for the night.

On the face of it, Empire was a departure for Warhol. Actually, scratch that: on the face of it, which was precisely where Warhol trained his gaze, the vaulting edifice was one more iconic American profile to add to his repertoire of Liz Taylors and dollar bills. He was essentially a portraitist, an inspired artist savant with the soul of a shutterbug on the Coney Island boardwalk, taking pictures of holidaymakers for a few clams a go.

I wondered aloud if Malanga had liked his old boss. He had, he said, especially when the pair of them were making silkscreen paintings together. ‘He was at his most relaxed.’

‘Did you ever see him without his wig?’

‘No,’ Malanga laughed.

All 102 storeys of the Empire State Building shrank into the gloom, and I found my resistance to Warhol’s film was also dwindling. The director’s gift for second sight was preternatural — or, if you prefer, he was lucky with his timing — and his filmic ascent of the tower has cast a long shadow. A group of conspirators clandestinely taping one office building from another irresistibly suggests the Watergate era of the 1970s. (Warhol, who recorded everything, was the Richard Nixon of the counterculture.) And of course, no one can look at a tall building in New York for any length of time now without thinking of the attack on the World Trade Center (which superseded the ESB as the tallest building in the world). When I looked up the history of Empire, I was struck by the fact that the fall day on which Warhol chose to shoot was 11 September.

Can you glean anything more from a camera shot by looking at it for hours on end? Is it comparable to spending the morning in front of the ‘Mona Lisa’, rather than the average time of 15 seconds reported by guides at the Louvre? I daresay it depends on the viewer, but perhaps it’s only now, when we embrace ‘mindfulness’ as the way forward, that we can fully appreciate the value of staring at a brick wall for eight hours at a stretch.

All I will say is that, dulled into low expectations as I may have been after my evening in front of Warhol’s biggest ‘superstar’, I knew a moment of keen and unexpected pleasure when her lights came on. It was at sunset, about half past eight, and she was lit up red, white and blue for Memorial Day. As David Shulman said, ‘What could be more Pop than that?’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in