These are nervous times at the opera. When should we expect the gratuitous rape scene? Will the director relocate the action to a Croydon laundrette? Who might be booed, and for how long? With Opera Holland Park’s Lakmé, however, almost any of these diversions might actually be welcome — anything to save us from the tasteful visual torpor that looms over Aylin Bozok’s production like a choking black cloud.

Consider the riot of colours embedded in Delibes’ opera. We’re in India in the late 19th century, where officers of the British Raj fly the flag and march to fife and drums. There’s a bustling bazaar and glinting jewellery. Sensuous hues burst from the music. Flowers creep in everywhere, from the luminous lotus to the poisonous datura. But what does designer Morgan Large serve up? Acres of dull blues, greys, khakis and in-betweens, pierced only by the gilded cage from which Lakmé, the fated heroine, trills her famous Bell Song. No wonder so many characters and chorus members lie on the floor, seemingly asleep.

What keeps forty winks at bay for us? The singing, fortunately, and Delibes’ score. So many riches lie beyond the Bell Song and the Flower Duet that it’s a mystery why most companies here give this opera the cold shoulder. Are they afraid of the Bell Song’s top E? The note is no problem for Fflur Wyn, though she’s closer to her best cascading to and from, or lancing the air with pinprick staccato. Infuriatingly, Bozok smudges the impression of her eight-minute carillon by filling the front stage with one of the show’s ‘Indian’ dances performed by Lucy Starkey, whose lurching hand movements suggest Harry Houdini pushing his way out of a trunk.

Elsewhere, good things roll out of tenor Robert Murray as the English officer Gérald, even when his character seems to have been stabbed by remote control. Stentorian bass notes distinguish Lakmé’s priestly father Nilakantha, sung by David Soar, while Nicholas Lester stands tall as Frédéric. The City of London Sinfonia, conducted by Matthew Waldren, lap up every woodwind caress and piquant phrase, and the chorus sing with much more vigour than their catatonic movements suggest. If only there were more eye candy here, and more of a sense of the Orient’s lure. French creative artists didn’t spend the 19th century sinking into clouds of opium for nothing.

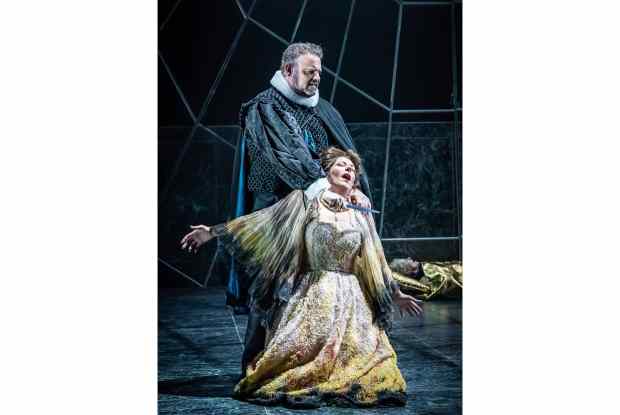

After the watery plod of this production, and Holland Park stage’s CinemaScope length, it was a joy at the Buxton Festival to sit in the Opera House’s compact splendour and clearly hear every note and throb of a greater rarity still, Verdi’s early, pulsating Giovanna d’Arco of 1845. It was a joy, too, to see a production where the director, the veteran Elijah Moshinsky, knows exactly what he’s doing, crisply marshalling the eventful libretto’s opposing forces (French and English, demons and angels, father, king and daughter) through Russell Craig’s simple slats, inventively illuminated by Malcolm Rippeth.

Given her schoolgirl smock in the Prologue, I briefly wondered if this Joan of Arc had been reconfigured as a pupil at some French offshoot of St Trinian’s, but the impression faded with every determined note from the Australian soprano Kate Ladner. There’s something of Juan Diego Flórez about her tone’s unvarying diamantine brilliance and searchlight power. No wonder the heroine, in this libretto, wriggles free from her stake to fight more battles and finally die after singing one aria too many. Nor are her male companions shrinking violets. Caparisoned in a blue fleur-de-lys pattern that would make brilliant Sanderson wallpaper, Ben Johnson sings his socks off as Carlo (otherwise King Charles VII), Giovanna’s earthly champion and lover. Devid Cecconi, meanwhile, supplies booming baritone gravitas as Giacomo, the shepherd father convinced that his daughter is possessed by devils.

Verdi’s music, admittedly, doesn’t plumb emotional depths, and it has its share of populist rum-ti-tum, the Devils’ Waltz included. But, boy, it has velocity as we’re swiftly switched from one chiselled situation to another. There are vigorous outpourings from the Buxton Festival Chorus, while the bright orchestrations give the Northern Chamber Orchestra and conductor Stuart Stratford much to feast on, from gorgeous eruptions of marching brass to the evening’s instrumental highlight in Carlo’s late romanza, a keening cor anglais wrapped round a cello.

Beyond the town’s Saturday carnival and the bustle of the Buxton Festival Fringe, the opening weekend also delivered Stephen Unwin’s disappointingly scrappy production of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, seemingly set at the dowdier end of the 1920s. Jonathan Fensom’s two backcloths and handful of props leave plenty of room for thoughts to wander, as do the two intervals. Adriano Graziani displays passion aplenty as Edgardo, but Elin Pritchard’s Lucia mixes secure top notes with fuzzy acting. Music apart, this isn’t an essential night at the opera.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in