For anyone who has been interested in classical vocal music since the middle of the last century, whether choral, operatic or solo, there has been one inescapable name and voice: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. His repertoire was gigantic, surely larger than that of any singer ever. He began public concerts and recordings in the late 1940s and only gave up in the 1990s, when he took to conducting and narrating, as well as painting, writing a large number of books about German composers (including a ridiculous one on Wagner and Nietzsche) and of course coaching young singers.

Such was his appeal that he not only recorded Schubert’s Winterreise several times with Gerald Moore and Jörg Demus, but also with Brendel, Barenboim, Perahia, Pollini, most of them unknown otherwise as accompanists. He even recorded Schumann’s Dichterliebe with Horowitz, of all bizarre conjunctions; and recitals with Sviatoslav Richter. His operatic repertoire was large, too, ranging from Don Carlos (in German) in 1948 to most of Verdi’s baritone roles, Scarpia, many Wagner roles, up to Reimann’s Lear, written for him. He often sang Bach, including an effusive Christus in several recordings of the Matthäus-Passion. If you listen to Radio 3 and a lied is played, the odds are overwhelmingly that it will be F.-D. I read someone the other day stating that ‘the art of the lied was revived single-handed by Fischer-Dieskau after the war’.

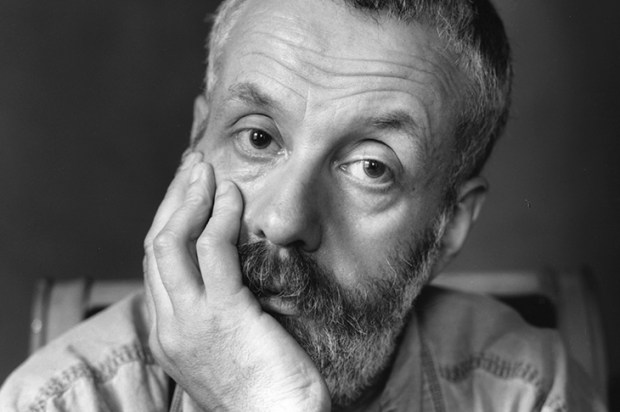

There have naturally been dissenting voices, perhaps most notably Roland Barthes, but also some German critics, and an occasional admission by admirers that he had a tendency to over-interpret in his later years. But there is a general agreement that he was incomparable for the first three decades of his career. I find, on the contrary, that he exaggerated at least as much when his voice was in its best shape, more in fact, since he could afford to take risks with it. Listen to him in Bayreuth in 1954 singing Wolfram’s apostrophe to the Evening Star (pictured above singing it in 1961), and a piece that is no more than a charming Victorian ballad is turned into something that might have been composed by Wolf, with ludicrous attention directed to every last syllable. He even, in his enormous number of Wolf recordings, manages to over-stress each word, turning brief songs into ‘meaningful’ slogs. Though he always stressed the centrality of legato, he was in fact notable for his explosiveness, his incessant disruption of line in the interests of ‘expression’, and his over-wide dynamic range, from hectoring shouts to crooning. He certainly was highly influential, but singers are only now starting to recover from his weirdly influential spell.

And as for the claim that he revivified the singing of lieder, it had no need of him. Anyone who looks at and listens to the pre-war EMI Wolf album will see what a prodigious number of great singers there were. And during the war the prodigiously energetic Michael Raucheisen aimed to record the whole of the lied tradition, with very many fine artists — there were innumerable volumes available on LP. And, to be as invidious as possible: what about Hans Hotter, not only the commanding Wagner bass-baritone from about 1937 for three decades, but also a surpassingly great interpreter of Winterreise and a huge range of other lieder, carrying on well into his sixties. Listen to them side by side and there just is no competition — but not many people will agree, to judge from my decades-long campaign.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in