The oceans cover seven-tenths of our planet, and although it may not seem like it above the surface, they are very busy. Helen Scales and Christian Sardet are marine biologists: Sardet is apparently known as Uncle Plankton, and those multitudes of drifting organisms — ‘plankton’ comes from the Greek planktos, meaning to wander or drift — are his life’s work.

Scales’s focus is the shell-making creatures that are molluscs, though focus seems an inappropriate word for such a vast body of life: a 1993 survey of just one island, New Caledonia, found 2,738 distinct species, and 80 per cent of them were new to science. They are ‘some of the most abundant, cosmopolitan animals on the planet,’ Scales writes, ‘not to mention being among the toughest, smartest and strangest creatures ever to evolve’.

They include the Gumboot Chiton, the Dismal Limpet, the Gooey Duck Siphons (a Chinese delicacy) and the Cooper’s Nutmeg Snail Vampires. And the abilities and behaviours of molluscs are as bizarre as their names. Gastropods, when very young, undergo a process called torsion, which involves ‘all the major organs spinning around 180 degrees’ so that the anus shifts to a position just above the mollusc’s head. Satsuma snails amputate their single foot when chased by snakes. There is the wonder that is shell-making, whereby molluscs excrete a scaffold of protein, layer it with calcium carbonate, and make shells that are beautiful, but also wonders of geometry and engineering. That’s the science, and it is interesting, but so are other notes I took: ‘surfing sea-snails’, ‘Clusterwinks burglar alarms’, ‘sperm-shooting’ and ‘the Belligerent Rockshell’.

If you buy a modern, pristine seashell, its inhabitant has probably been killed for the seashell trade. The human relationship with seashells has been one of delight, but also of exploitation. Cowries were one of the first currencies, and widely used in the slave trade. The oldest jewellery discovered was made from dog whelk shells and worn by a North African people 100,000–125,000 years ago. Aztecs may have used spondylus meat as a mind-altering substance.

Humans today eat 16 million tonnes of molluscs a year, an industry worth £3 billion. Clams and mussels, of course, but also whelks — molluscs that are abundant in British waters but which are eaten only in Yorkshire pubs and by South Koreans. Shells can do more for us than provide food: scientists are now trying to make a bio-glue from the substance mussels produce to stick themselves to rocks, which could be used, for example, to repair foetal membranes. The neural jamming properties of conotoxins, ‘the most complex poisons on the planet’, that are emitted by cone snails are being studied for therapeutic use in epilepsy, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

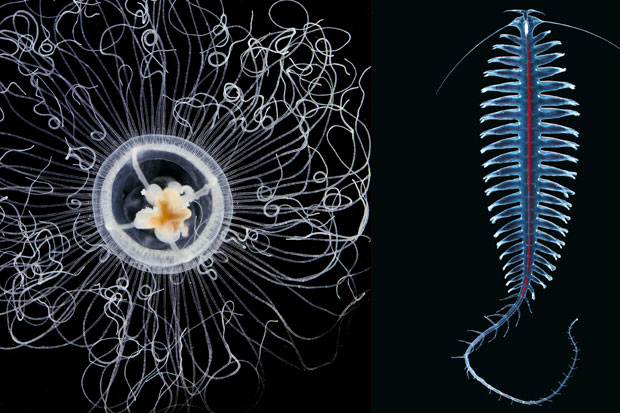

Humans are even more indebted to plankton, the organisms that make up 98 per cent of the ocean’s living biomass and which are brought vividly to life in Sardet’s microscopic images. Every other breath we take has been filtered by the ‘single-celled photosynthetic drifters’ called phytoplankton. Photosynthetic bacteria and protists produce as much oxygen as all the forests and terrestrial plants combined.

That is what molluscs and plankton do for us. But what do we do to them? It is surely impossible now to write about the ocean without mentioning its worst affliction: humans. Sardet touches on environmental damage but lets his stunning images speak louder than his sober scientific text. Scales goes deeper, examining the disappearance of oyster beds: 85 per cent of oyster beds, banks and reefs are gone. In a charming bit of reportage, she introduces us to the oyster women of the Gambia, who fetch oysters from mangrove swamps in a sustainable initiative, and who wrestle each other at an annual festival. She writes of algal blooms, which are increasing, probably due to the agricultural run-off and sewage we thoughtlessly tip into the ocean. With more algal blooms, there is more shellfish poisoning: 2,000 reported cases a year in the 1980s; now 60,000.

Both writers point out that without the capacity of the oceans to absorb carbon, our above-water environment would be in an even direr state than it is. But it is not a limitless capacity. Already, the quantity of carbon in seawater may be melting some seashells; and planktonic ecosystems, writes Sardet, ‘are already subject to tremendous stresses from rising atmospheric CO2, and ocean acidification, overfishing and various forms of pollution’.

These books are not flawless: Sardet’s images are vital, vibrant and stunning, but his text can lack energy at times, while Scales’s attempts at chumminess grate (‘chompers’, ‘titchy’, ‘in-betweenie’, ‘the big blue’). But these quibbles are bits of grit in an oyster shell, and grit gets covered by a pearl. We are used to thinking of seashells as empty, or plankton as microscopic and irrelevant. Both books puncture these assumptions with the power of a cone snail dart.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'Spirals in Time: The Secret Life and Curious Afterlife of Seashells', £13.99, and 'Plankton: Wonders of the Drifting World', £28 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in