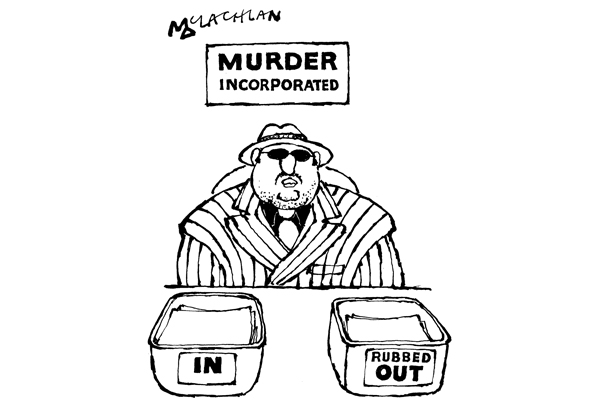

At the eye of apartheid South Africa’s storm of insanities was a mania for categorisation. Everything belonged in its place, among its own kind, as if compartments for scientific specimens had been laid out across the land. Or, as Christopher Hope puts it in his caustic new satire, people were ‘corralled in separate ethnic enclosures, colour-coded for ease of identification’.

Reminding us that ‘Jim Fish’ was a derogatory term for a black man in South Africa, Hope thrusts his eponymous hero, who fits no racial category, into this mad system of classification. To some, Jimfish appears ‘as white as newly bleached canvas’, to others ‘faintly pink or tan or honey-coloured’. Nonetheless, racist whites treat him as ‘not the right sort of white’. Forced into menial work, he comes under the influence of autodidact philosopher-revolutionary Soviet Malala, whose firebrand Marxist populism convinces Jimfish that, whatever else, one must fight to be ‘on the right side of history’. History, unsurprisingly, has other ideas.

Beginning in 1984, Jimfish sets out on a decade-long globe-trekking odyssey of disillusion that takes in Zimbabwe, Uganda, Chernobyl, Siberia, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the last days of Ceaucescu, Mobutu’s Zaire, the Liberian civil war and Somalia. Though funnier and more anarchic than Orwell, Hope is similarly concerned with the grotesqueries of totalitarian systems and the Kafkaesque contortions of late 20th-century geopolitics.

As Jimfish makes his way through West and Central Africa, the book achieves something of the quality of Evelyn Waugh’s Black Mischief and Scoop. By now, South Africans are no longer ‘polecats and pariahs’ but desirable mercenaries with the best ‘armaments, muscle, money and business acumen’ on the continent. How quickly the political sands shift, while little actually changes: one cruel regime usurps another; an outcast at home becomes a hero abroad.

Juxtaposing sardonic swipes at the hypocrisies of the powerful with moments of brutally realistic horror, Hope seems to suggest that our contemporary world’s nightmares are as absurd as they are appalling. Fleeing the gruesome public display of Liberian President Samuel Doe’s mutilated body, Jimfish at last recognises his knack for arriving in a place just at the moment things start going to hell. A CIA operative is convinced Jimfish himself is the one who brings disaster: ‘You’re a force of history. A one-man weapon of mass destruction.’ At CIA headquarters they admiringly call it the ‘Jimfish effect’.

If Hope’s hapless Everyman knows little of the wider world in the beginning, he comes to believe that human delight in cruelty makes us what we are, ‘homicidal apes who kill their own … and afterwards write moral commandments’. One might imagine there could be no quarter left for hope in such an acerbic view of recent history. Not so. Having returned to South Africa, and watching as Mandela takes the oath of office in 1994, Jimfish senses he has finally arrived on the right side of history. How quickly, though, we feel certain of that moment’s passing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £13.99, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in