Nothing is capable of undermining American democracy more than its legal system. Amid the plea bargains, perp walks and 95 per cent conviction ratings for some crimes, one feature of the system stands out as particularly rank — the role of ‘special prosecutor’. A new piece of evidence relating to a high-profile conviction eight years ago provides a perfect demonstration.

The case relates to a legal dispute spanning President George W. Bush’s period in office. In late 2003 the situation in post-war Iraq had already begun to go horribly wrong. In the US, many who had eagerly supported the invasion and warned of the risks of WMD were flaking away and seeking scapegoats. In the ‘Plame affair’, the perfect outlet seemed to have been provided.

The case revolved around the ‘outing’ of a CIA officer, Valerie Plame. Her husband, the former US ambassador Joe Wilson, had been sent to Africa to inquire into claims by British intelligence that Saddam Hussein had been trying to buy uranium. There was a dispute over the findings and their use and Wilson publicly turned on the administration. For this reason, it was alleged, someone in the administration vengefully ‘outed’ his wife as an agent of the CIA. The case always involved too much detail, and too many egos, personalities and ambitions, to be remotely straightforward. But as the situation in Iraq deteriorated it seemed to many to provide the most promising legal stick with which to beat the administration.

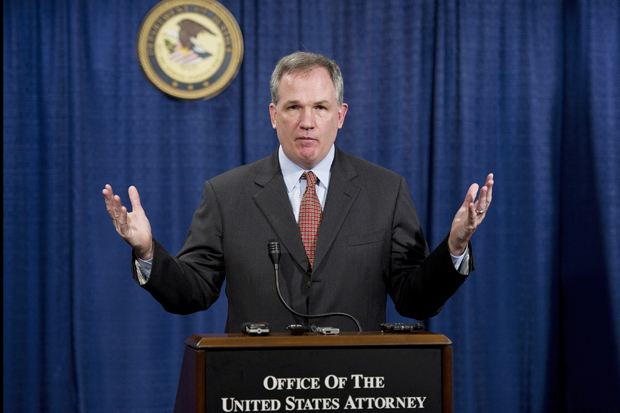

In order to find the leak, one Patrick Fitzgerald was appointed special prosecutor. It is a position from which major careers can be made, and so appointees tend to view anything from oral sex to an off-record conversation as a Watergate scandal in waiting. Fitzgerald duly threw himself into the role, summoning, questioning, and hauling before grand juries both journalists and members of the administration.

We now know that from the time of his appointment in December 2003 Fitzgerald had already known that the person who had first leaked Plame’s identity to the columnist Robert Novak was Richard Armitage from Colin Powell’s office. This fact was publicly disclosed in 2006. But that clearly wasn’t enough for Fitzgerald’s appetite, and so the hunt went on after the source had been found. Along the way Fitzgerald discovered that the star New York Times reporter Judith Miller had had several conversations with Scooter Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff. Miller had never even written about Valerie Plame — the only cause of the investigation being ordered — but Fitzgerald ordered her to hand over her notebooks anyway. Miller refused, citing her journalistic duty to protect sources, and so went to prison for three months for protecting sources over a story she never wrote.

All the time Fitzgerald clearly had higher targets in his sights. Special prosecutors have two particularly effective weapons available to them. The first is to wear their subjects down, chasing them from charge to charge until they can find something — anything — even if it has to be ‘obstruction’ during an investigation that need never have commenced. The second is to offer them a way out by handing over someone higher up. Fitzgerald appeared to deploy both tactics shamelessly. On at least two occasions, as the investigation dragged on, Libby was told that all charges against him could be dropped if he only ‘delivered’ his boss, the Vice President. Because there was nothing to ‘deliver’ on Cheney, Libby refused. So Fitzgerald continued the pursuit. By the time Scooter Libby was tried in 2007 it wasn’t for anything to do with the Plame leak — everyone then knew Armitage had taken responsibility for that — but for lying to federal officials about what he had said to three reporters, including Miller.

It is relating to this part of the story that an extraordinary new piece of information has come to light. After her spell in prison, and with her job on the line, Miller was eventually worn down to agree to hand over some redacted portions of notes of her few conversations with Libby. Several years on, she could no longer recall where she had first heard of Plame’s CIA identity, but her notes included a reference to Wilson alongside which the journalist had added in brackets ‘wife works in Bureau?’ After Fitzgerald went through these notes it was put to Miller that this showed that the CIA identity of Plame had been raised by Libby during the noted meeting. At Libby’s trial Miller was the only reporter to state that Libby had discussed Plame. His conviction and his sentencing to 30 months in prison and a $250,000 fine, rested on this piece of evidence.

But Miller has just published her memoirs. One detail in particular stands out. Since the Libby trial, Miller has read Plame’s own memoir and there discovered that Plame had worked at a State Department bureau as cover for her real CIA role. The discovery, in Miller’s words, ‘left her cold’. The idea that the ‘Bureau’ in her notebook meant ‘CIA’ had been planted in her head by Fitzgerald. It was a strange word to use for the CIA. Reading Plame’s memoir, Miller realised that ‘Bureau’ was in brackets because it related to her working at State Department.

At his trial, Libby’s defence team had tried to bring in Harvard’s Daniel Schacter to testify. Schacter is an expert in memory and author of the brilliant and haunting book The Seven Sins of Memory. He would have shown how common ‘misattribution’ — the way in which people replace one version of memory with another — can be. The judge rejected the witness, but the jury could have done with him. Years after her interviews with hundreds of interviewees, Miller had had it suggested to her that her source for hearing about Plame was Libby and she had erroneously agreed.

Why does all this matter? First, because Scooter Libby was wrongly convicted and remains unpardoned. Secondly, because of the insight the case gives into the failings of American justice. Libby and Miller are relatively lucky people, with voices and some remaining influence. How many people with no profile or defenders fall victim to such politicised or careerist prosecutors?

And finally, it matters because of the damage the whole sorry affair did to America and Iraq. The administration made whole piles of errors, but members of the administration have admitted in recent years that the investigations into the Plame affair distracted the entire White House at a time when its single-minded focus was desperately needed elsewhere. Libby had been an advocate — from 2003 — of a ‘surge’ operation in Iraq, increasing forces to protect Iraqi lives. Fitzgerald’s pursuit not only forced him from office but significantly absented from discussion a policy which Libby was then (four years before the ‘surge’) almost alone in advocating. The final irony of the whole case is that the special prosecutor wanted to locate a Watergate. What he did instead helped fan a Vietnam.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Douglas Murray is an associate director of the Henry Jackson Society, and the author of Neoconservatism: Why We Need It. He blogs at spectator.co.uk/douglasmurray

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in