The Ice Break is Michael Tippett’s fourth opera, first produced at Covent Garden in 1977 and rarely produced anywhere since, though there is an excellent recording of it. Its brevity (75 minutes) rather took the wind out of the Royal Opera’s sails, since they had envisaged a full evening’s piece. So, I imagine, did its wackiness, though more extreme things in that line were to follow from Tippett. There are numerous ingredients in The Ice Break, but it gives the impression that its composer was so fascinated by all of them that he restlessly moves from one to another, leaving his audience to see whether they can make sense of them. As with his previous opera, The Knot Garden, almost all the characters have strange names — Lev, Yuri, Olympion, Astron etc. The crowd plays a very large role too, as suits the BOC, and it can’t be said that the musical style of the work is unified either. The text, Tippett-written as always, mixes the trendy, slangy and vatic in a disconcerting way. Despite all of that, I emerged energised and fascinated by the intensity of Tippett’s search for a vision, almost certain that he hadn’t found one, but more absorbed by his failure than I would be by most composers’ success.

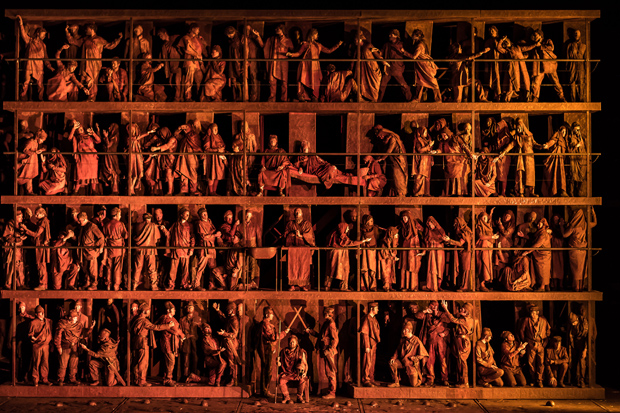

The production, perhaps BOC’s most ambitious to date, took place in the B12 Warehouse, in a part of Birmingham unique, so far as my travels to the various BOC sites go, for its desolation and air of hopeless collapse. Perhaps it justifies the importing into the production of a set of contemporary anxieties that complicate an opera already over-burdened by its concerns: for the warehouse is transformed into an airport terminal, and as the audience arrive they are treated as if arriving at Terminal 3. And throughout the opera, which as usual has rapid changes of location, the chorus, enacting several roles, enjoys shoving the spectators around, hugging selected ones, being bossy. I think this trope, though it is the most obvious way to involve members of the local community in the action, has been used enough now. As have overpoweringly bright lights to illuminate the scenes of action. But one doesn’t go to BOC for any kind of comfort.

What one does go for, and is never disappointed, is continuous surprises, superb singing and acting, and nowadays the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra playing resplendently under difficult conditions, with the unflappable conductor Andrew Gourlay. This isn’t perhaps the way to get inside a piece, but it works to inspire interest in it and to show that opera, all considerations of elitism aside, is both an extremely demanding art form and an electrifyingly thrilling one. The all-round standard of singing is so high that I reluctantly can’t mention the performers, except for Chrystal E. Williams, who sings Hannah, and in the centre of the work has an aria, ‘Stranger and darker, deeper into myself, Blue night of my soul’, of that kind of comforting beauty in bleak circumstances which Tippett has cultivated from A Child of Our Time onwards.

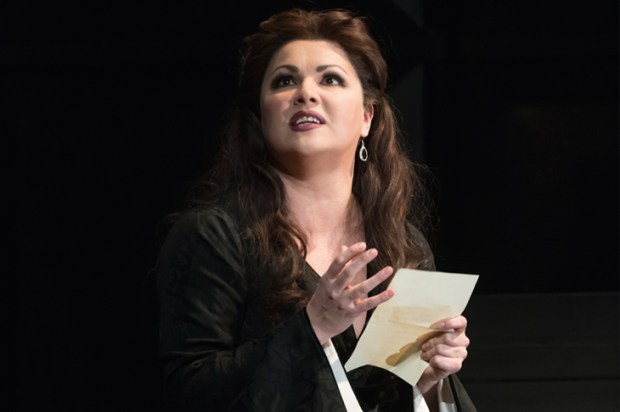

The week before I had gone to the Royal Opera’s latest revival of Madama Butterfly, in the undistinguished but inoffensive production by Leiser and Caurier. Actually Butterfly hardly needs producing, except in the sense that operas were in the 1940s. This revival was remarkable for the conducting of Nicola Luisotti, a familiar figure here; but this was by far the most distinguished effort I have heard from him. He took a broad view of the whole score, but without mannerism he touched on so many details that it was almost a revelation. What really was a revelation, if a recurring feature can be called that, was the singing and acting of Kristine Opolais. Her performance has become more detailed, especially in gesture, than it was, and I’d say she is not only the most moving Butterfly I have ever seen, but that it’s impossible to imagine a finer one. All the supporting roles were well taken, and if Brian Jagde doesn’t have quite the swagger that Pinkerton needs, he still cuts a plausible figure, and even manages to be dignified in his futile repentance.

When Butterfly is performed as well as this, one does have to ask why one wants to sit through it — and this revival was, as always, a sell-out. What we are watching and hearing is the detailed and utterly convincing torment of a completely sympathetic woman, as she moves towards her tragic doom, set to gorgeous music, perfect in every bar apart from the long orchestral passage that links Acts II and III. Why do we do it, why do we crave it? I refuse to agree that Butterfly is kitsch or anything like it, and I can honestly say that I was upset for several days after seeing it. I have even vowed that I won’t see it again, at least until I can justify what seems an act of spectatorial masochism. The oldest, biggest question in aesthetics, and no one has produced an even plausible answer.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in