In December 1878 Vincent Van Gogh arrived in the Borinage, a bleak coal- mining district near Mons. He was 25 years old. He’d failed to become an art dealer. He’d failed to become a schoolteacher. Drawing was just a hobby — an artistic career was the last thing on his mind. He’d come here as a preacher, full of evangelical fervour, yet he proved a failure at that too. The problem was, he was far too pious. He gave away everything he owned. These miners didn’t know what to make of him. They called him ‘the Christ of the coal mines’. After six months, he was fired. With nowhere else to go and nothing else to do, during the next 18 months Vincent taught himself the rudiments of draughtsmanship, anatomy and perspective. By the time he left, in 1880, he’d become an artist. ‘The Borinage is every bit as picturesque as Venice,’ declared Van Gogh, improbably —proving beyond all reasonable doubt that he really was completely bonkers.

When Mons won the bid to be this year’s European cultural capital, a show about Van Gogh’s creative advent in the Belgian collieries was an obvious idea. There was only one problem: Van Gogh destroyed almost every artwork he made here. As the curator of this exhibition Sjraar Van Heugten explains, a display of surviving pictures from this period could easily fit on to a small table. Van Heugten has rounded up a few simple sketches that escaped Vincent’s purge, and some of the letters he wrote to his brother Theo during his artistic apprenticeship amid the slag heaps. But for most exhibits, he’s had to look elsewhere. What he’s come up with is actually much more interesting — a survey of how the Borinage shaped Van Gogh’s career.

What Van Gogh encountered in the Borinage was a group of people he could relate to (whether they could relate to him was another matter). He was inspired by their stoicism, he sympathised with their hardships. ‘He wanted to mean something to those poor people,’ says Van Heugten. He’d failed to do it as a preacher, but as a painter he succeeded. His empathy was echoed in all his subsequent portraits of working men and women. The workers in his pictures are always dignified, but they’re never sentimentalised. This was because he really knew them. He understood the pattern of their lives. ‘Most of them can’t read, yet they’re shrewd and nimble,’ Van Gogh told his brother. ‘They’re skilled at many things and work amazingly hard.’ Living with these mining families reinvigorated him. This was his Road to Wigan Pier. ‘It was in this extreme poverty that I felt my energy return,’ he wrote to Theo. ‘I can’t tell you how happy I am to have taken up drawing again.’

The pictures Van Gogh drew of the Borinage are pretty rudimentary. You can see why he was so keen to get rid of them. Far more impressive are his copies of Jean-François Millet (one of the founders of the Barbizon school of painting), through which he developed his own style. Van Heugten has united various versions of the same sketches, some of which have never before been seen side by side. The comparisons are fascinating. Two early drawings of ‘The Diggers’ (after Millet) show how Van Gogh would work and rework a single image. A later painting shows how he’d return to these early studies once his art was fully formed. In a drawing and a painting of Millet’s ‘The Reaper’, from 1880 and 1889, you can trace his evolution as an artist. ‘The Borinage …will always be unforgettable to me,’ wrote Van Gogh. Van Heugten shows you why. ‘Van Gogh was a remarkably disciplined man — once he made choices, he stuck with them,’ says Van Heugten. Sticking with the same motifs gave him a firm foundation. It freed him to run wild.

A lot of the pictures Van Heugten has hung in here are difficult to warm to — grim studies of run-down cottages, painted in thick muddy browns. Miserable bastard, you can’t help thinking. No wonder he never sold any paintings. Van Gogh completists will love it. Casual visitors may be disappointed not to find more familiar classics. This isn’t so much a greatest hits compilation, more a collection of rare B sides. But then you arrive at ‘Rue à Auvers-sur-Oise’, painted in the last months of his short life, and you realise what Van Gogh had been building up to. The gloomy Borinage got him started. All he needed was some southern sunshine to bring these grimy daubs to life.

Today the Borinage is a quieter, cleaner place. The slag heaps are grassed over. The mines have closed. Two of the modest houses where Van Gogh lived are being restored and renovated as museums. This attempt to put the Borinage on the tourist trail is richly ironic. It was the desolation of this sooty netherworld that turned Van Gogh into a great artist. The Belgians will never make it pretty, however hard they try. ‘Everything around it has something dismal and deathly about it,’ wrote Van Gogh, of his first trip down a mine. ‘The villages here have something forsaken and still and extinct about them, because life goes on underground instead of above.’

Compared with these forlorn surroundings, Mons is a nice surprise. Nobody in their right mind would call it beautiful, but it’s a pleasant spot to spend a weekend. The Grand Place is a medieval marvel — the gothic cathedral is a gem. The old town is littered with antique architecture: the baroque belfry, the ornate town hall… There are some bold modern buildings, including a smart new Congress Centre by Daniel Libeskind, though the preparations for Mons’s year as EU Capital of Culture have been somewhat tardy — the new train station, by Santiago Calatrava, is still a building site.

For Britons this will always be the place where the first world war began and ended — the first and last British casualties, John Parr and George Ellison, are both buried in the local cemetery, St Symphorien, almost side by side. Beaux-Arts Mons has now given us another good reason to visit this gritty city and its industrial hinterland. Van Gogh in the Borinage isn’t a spectacular blockbuster, but it’s a retrospective with a proper purpose. It sheds fresh light on his painting — not only his early years, but his entire oeuvre.

Van Gogh’s suicide, in 1890, went entirely unreported in the Belgian press, but in the summer of 1914 six of his paintings were exhibited here in Mons, at the handsome Hôtel de Ville. The art critic from Le Hainaut didn’t think that much of them, apart from a ‘violent’ painting of some sunflowers. Le Journal de Mons was more enthusiastic. ‘Un Grand Artiste’ announced the local paper. Art was a religion, wrote its anonymous reporter, and Van Gogh was an apostle, who’d raised art far above his individual life into the infinity of humankind. ‘He felt he had to work withou t ceasing,’ observed this unknown hack, ‘to express the emotion that consumed him.’ The show closed in July. Van Gogh’s paintings were sent back to Amsterdam. Six weeks later, Mons became the first British battlefield of the Great War.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

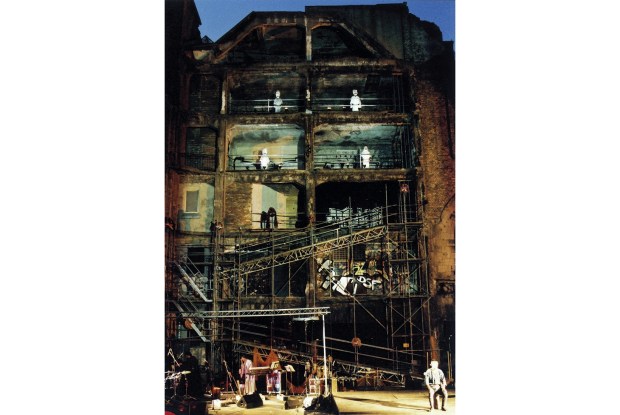

Van Gogh in the Borinage – The Birth of an Artist is at Beaux-Arts Mons, until 17 May.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in