There’s something wrong with the relationship between patients and their GPs. I’ve spent much of this winter in my local surgery, what with one thing and another, sitting among the stoic and snivelling, drifting between different doctors. They’re pleasant, if perfunctory, but with each visit I became more sure that something fundamental is awry.

The docs seem ill at ease, as if their collective nose is out of joint, and I don’t think it’s overstretching or underfunding that’s the problem. My unprofessional diagnosis is that there’s a change under way in the balance of power between patients and medics; the status of GP as unimpeachable oracle is under threat, he feels the first tremors of what may be a seismic shift, and he doesn’t like it.

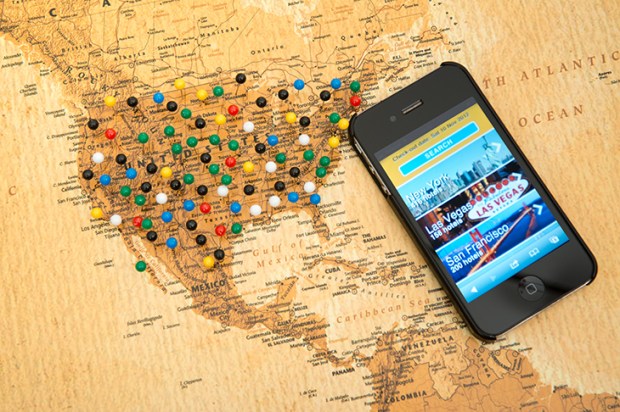

For more than half a century, since Christianity first faded from public life, GPs have been our secular high priests. They’re the guardians of birth and death, the purveyors of pills, and we’ve hung on their every word. Now, thanks to the internet and apps testing heart rate, fat and fitness, we’ve all become de facto quacks. At night, by the light of a touchscreen, we scroll through the latest medical guidance, and the doctor no longer seems like a miracle man.

Take my own experience. I’ve always secretly enjoyed a visit to the doctor. I like the rituals, pulse-taking and blood pressure. I like the pebble cool of a stethoscope and the superior sing-song way a GP says: ‘Breathe in … and breathe out.’ I’m a doctor-pleaser, the very model of a deferential patient, except that these days I often know more about my own long-term ailments than the GP, and I sometimes can’t help but mention it (in a tentative and respectful way) when the doc’s out of date. At which point I become the enemy.

The GP turns away, deploys a selective deafness usually used by grandmothers. If he speaks at all, it’s to the effect that my information is both unwelcome and irrelevant. I have offended against the protocols of healthcare, so I sit for the rest of the consultation silent and panicking, now repentant and regretting ever alienating the powers that prescribe.

It reminds me of the dynamic between taxi drivers and passengers, changed now and forever by Google Maps. The Knowledge isn’t exclusive any more — it’s available to all, complete with traffic reports updated in real time. The cabbie is no longer king — even so, he clings to his throne for dear life and it’s a brave passenger who suggests that Google might know best.

But in healthcare, especially primary care, there’s another very particular danger in the doctor/patient relationship. It’s not just that the GP’s bedside manner might evaporate, but that the cure might vanish with it.

It’s a curious fact of our biochemisty that the very trust we place in doctors, that semi-religious deference, contributes to their healing powers. This is true not just of hypochondriacs like me, but of everyone. It’s the mysterious placebo effect and no one, however steely, is immune.

A placebo is the duff sugar-pill that researchers use as a control when testing new drugs. It has no active ingredients, but even so, through faith and expectation, it can have a considerable curative effect. If a patient, given a placebo, is told he’s getting a ‘stimulant’, his pulse rate speeds up, his blood pressure actually increases. If he’s given a large, potent-looking pink pill, or one stamped with a well-known brand, his headache vanishes quicker.

What’s true of pills is true of doctors too. Patients treated by medics dolled up in white coats with badges saying ‘senior surgeon’ recover better than those treated by GPs in jeans. Faith matters in medicine; our expectation of getting better plays a crucial role in recovery, which is why it might be quite a serious matter if we lose our unquestioning admiration for GPs. Their pills would lose their mojo, patients would languish for want of believing they’d get better. What a weird revenge it would be for doctors if the effect of our disenchantment in them was that we suffered more.

But as with taxis, so with medical matters. When humans prove fallible, machines step up to fill their shoes. Are you prepared for your first consultation with Doctor Droid? Because he’s out there preparing for you. Do you remember Watson, the IBM computer who beat contestants on the American quiz show Jeopardy? Quiz shows weren’t his ultimate ambition, it turns out. He’s currently retraining as a GP, reading and absorbing thousands of medical papers. His handlers say he’s becoming better at diagnosing patients every day; and I have to say I’m not entirely hostile to the idea.

Just think: Dr Watson would know all the new guidance, every cure and caution, from the second it was published on the line. He’d cross-check data in a nano-trice and never descend into a huff. Normal doctors are susceptible to something called anchoring bias — a human’s tendency to rely too heavily on a single piece of information. A physician hears two of three symptoms, decides on a diagnosis consistent with those, then rejects any evidence that might contradict the diagnosis. A related problem comes when he lights upon the right diagnosis but stops there, without realising that other conditions may be present too. Dr Droid wouldn’t let you down like that. But what of the placebo effect? Without the authority of a human, would it still have its crucial curative effect?

Who knows, perhaps the placebo effect will work double-time with a droid. If the internet’s his oyster, why shouldn’t a patient’s confidence soar? I see no reason that Dr Droid shouldn’t be programmed with the voice and manner of an old-school GP. My Dr Droid would have the pleasantly superior drawl of a prelapsarian medic, the high priest’s confidence without his need for obeisance. It could be the best of both worlds.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in