Whether by chance or bold design, the Royal Opera’s two Christmas shows were written at precisely the same moment, between 1857 and 1859, and both mark a high point of refinement in their respective traditions. Both Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Verdi’s Ballo in maschera sometimes give the impression of being entranced by their abstract musical fantasy; the drama on stage is suspended, drawn out, barely engaged with as the characters and audience peer down into the writhing or transfixed world being created in the orchestra pit. In my view, neither composer ever did anything better in musical terms. But sometimes you feel that there is no hope for Ballo.

The catastrophic history of Ballo at the hands of the censors, who insisted on renamings and rewritings so that no monarch would be assassinated on the operatic stage, is well known. Did that account for the amateur quality of the drama? Oscar, thrilling favourite of the untiring soprano, a Heldensoubrette role above all others, serves absolutely no dramatic function at all — he doesn’t even inadvertently identify the king to the assassins in the last act. What’s the point of the fortune-teller Ulrica? The king goes to see her for no very good reason, and she tells him the plot of the rest of the opera; the king’s love interest goes to see her, and she is told to gather herbs at midnight in a graveyard to cure her illicit passion. She doesn’t do any of that, and the whole business seems to be contrived to enable the two to meet at midnight over a tomb. Some further absurd business needs to be entered into to explain why the husband, too, finds himself in the same place at the same time of night. Why couldn’t the lovers meet at four in the afternoon over a cup of tea? God knows.

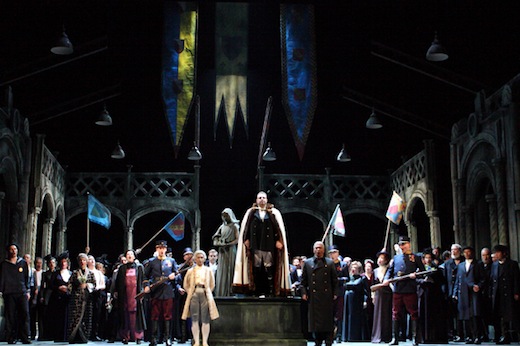

The inadequacies of the libretto, however, don’t excuse the limp production at Covent Garden. Set in a Balkan court just before the outbreak of the Great War (Oscar is being bundled off to the trenches as the curtain falls), the direction is seriously lacking. The principals mostly line up along the footlights and sing in a line; the chorus are blocked and immobile as if they were in an oratorio. The director, Katharina Thoma, has exercised her invention in adding some statues that come to life and strike poses, noticed or not noticed by the characters. She would have done better to have considered how the characters might behave towards each other.

George Bernard Shaw, contemplating the almost unprecedented comedy of Falstaff, pointed out that Ballo, 30 years earlier, has passages of exquisite bubbling lightness that might easily serve a comedy, like the sardonic ‘È scherzo od è follia’. It’s certainly one of Verdi’s most entrancing scores, and the second act in particular supplies a sequence of magically inventive numbers, culminating in an extraordinary, yelping love duet, like hounds in a hurry. It was disappointing to hear it done so carelessly. Despite the production asking the singers to line up and face the conductor’s beat, the ensemble was decidedly scrappy; in the big choral episodes, the ideally unanimous rat-a-tat of Verdi’s fervent calls to arms sounded more like a big pack of cards being riffled, and in the ball scene on the first night, the whole thing came dangerously close to falling apart completely. Conductor Daniel Oren couldn’t persuade the orchestra into the properly superb effrontery the style demands until the third act. Perhaps they were tired between Tristans, very understandably.

The cast seemed somewhat under-directed. Dmitri Hvorostovsky, a house favourite, gave exactly the same account of Renato he would have given in any other production, I dare say. Joseph Calleja is an unsubtle, quite enjoyable sort of tenor, but Riccardo is the one role here that might reward some subtlety. The advent of supertitles in the opera house has had all sorts of curious effects on singers, and Liudmyla Monastyrska, a stately, sumptuous presence as Amelia, made a lovely melismatic sound, but I have to say that I could only make out one word in 40. (I counted.) Serena Gamberoni was a pert, untiring Oscar. Sometimes I think opera houses only put Ballo on if they can be sure of a really impressive Oscar, like Zerbinetta in Ariadne. But an Oscar who can sing all the notes is not going to make an evening; though this curious role may present the most obvious musical challenges, it’s not really where one should start.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in