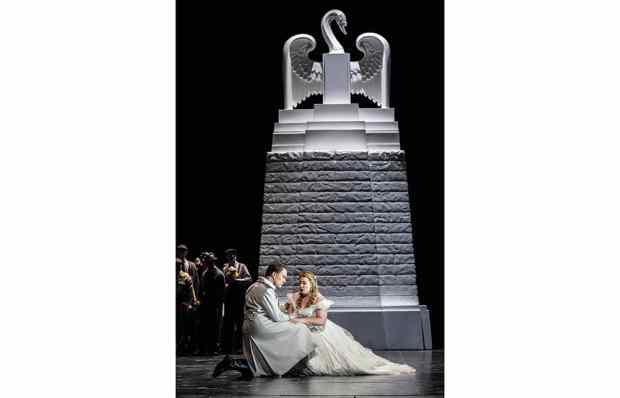

The big London companies gave two UK premières in the space of a week, both dealing with the subject of teenagers being shot dead. Kaija Saariaho and Sofi Oksanen’s new opera Innocence was premièred at the Aix-en-Provence Festival in 2021 and comes to the Royal Opera in exactly the same production by Simon Stone, the Australian director responsible for that lockdown favourite The Dig as well as a shattering staging (in Munich, in 2019) of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in