For those who imagine the medieval period along the lines of Monty Python and the Holy Grail — knights, castles, fair maidens, filthy peasants and buckets of blood and gore (you know, all the fun stuff) — Johannes Fried’s version may come as something of an aesthetic shock. His interests lie in the more rarefied world of theologians, lawyers and philosophers. So while the kings and emperors of the Middle Ages are afforded largely thumbnail sketches, it is the likes of Thomas Aquinas, Dante Alighieri, William of Ockham and Peter Abelard that attract Fried’s closest attention in his study of the ‘cultural evolution’ of the Middle Ages.

Fried, the éminence grise of German medievalists, takes a typically Teutonic approach to history in pursuing a big idea. He is well known (and a little controversial) in his native land as a proponent for the study of history as a ‘cognitive psychology’ and ‘life science’ and for championing ‘neuro-cultural history’. His preface to The Middle Ages is a little choked with some indigestible slabs of relativism:

Our focus… is therefore a construct, necessarily subjective…. It is a hypothesis, whose plausibility is conditioned by unprovable premises, our own subjective experiences, and familiar structural patterns…. Likewise, the simultaneity of events also defies any authoritative account, since once such an account has been given, it is forever consigned to posterity, and is only capable of sequentially considering, combining, or describing things that in actual fact had a concurrent effect and were contingent upon one another and intermeshed in their impact.

If that doesn’t have you reaching for the Rennies, nothing will.

Had Fried not flagged it up, you would be unaware of this propensity, shared, sadly, by too many academic historians, for historiographical navel-gazing. For when he warms up Fried, thankfully, just gets down to the business of writing excellent history in this absorbing book. In his successful endeavour to demonstrate that the Middle Ages was not ‘an era hopelessly ensnared in a kind of self-inflicted intellectual immaturity’, Fried makes even such topics as nominalism and dialectics come alive.

He achieves this by sensibly focusing on individuals to draw the reader into key themes and ideas. Thus the chapter on the ideas of Boethius, author of the hugely influential Consolation of Philosophy — favoured and translated by Alfred the Great, no less, as an abiding comfort in adversity — begins: ‘Boethius, the most learned man of his time, met his death in the hangman’s noose.’ This immediately arresting opening is typical of Fried’s treatment of his topics. Keen to show the evolution of ‘a culture of reason’, Fried brings in Boethius at various stages of the book, as when he is discussing William of Ockham’s nominalism, which promoted chance, contingency and individuality as governing reality. Fried states that ‘the ramifications of this position for scholarship were immense and are still felt today’. We are familiar with the concept of Ockham’s razor, in which simple explanations are to be preferred to more complex ones (something Fried might have considered applying to his preface).

He reminds us that the evolution of reasoning had a human cost. While Mother Church produced great and favoured thinkers such as Aquinas and Francis of Assisi, she also nurtured in her womb young who would turn on her and challenge her as an obstacle to progress. In an age when the line between heterodoxy and orthodoxy was a very fine one, many were prepared to walk it. It is salutary to consider how brave, even reckless and arrogant, many of the great minds were. William of Ockham flirted perilously with heresy, accusing the ‘pseudo-pope’ of ‘heretical error’ for defending the wealth of the Church when the reform movement towards apostolic poverty remained vital.

He escaped imprisonment by fleeing to the court of the emperor Louis IV in Munich, where he bounced ideas off a fellow intellectual refugee, Marsilius of Padua, who had sought sanctuary with Louis for his Aristotelian inspired revolutionary work, Defender of the Peace (Defensor Pacis) of 1324, which challenged papal omnipotence as a threat to peace. And a threat to himself: he knew he was on dangerous ground so published it anonymously (but not anonymously enough, as it turned out). His view, that the Church’s role should be restricted to that of moral arbiter while secular authorities decided matters of state, was latched onto by early Protestant reformers and ambitious princes, thereby providing Fried another example of the evolution of ideas.

The early-12th-century thinker Peter Abelard also diced with danger on an intellectual as well as a sensual level. He is most famous today for his doomed love affair with Héloïse, which led to her angry relatives castrating him. (He was lucky. Fried might have mentioned a medieval morality tale in which a woman is found by her brothers in flagrante delicto with a monk: they castrate him, hurl his dismembered parts into her face and force her to eat them; the lovers are then drowned. Clearly the lowbrow could compete with the highbrow.)

But in his own day Abelard’s chief notoriety lay in his ideas, which were heavily criticised for trying to marry religious and philosophical concepts in the pursuit of scholastic inquiry. He was imprisoned for heretical views on the Trinity and earned the enmity of another towering figure, Bernard of Clairvaux. Fried reminds us that the 12th century witnessed its own renaissance in learning, sadly overshadowed by the more attention-grabbing and pulchritudinous quattrocento affair.

Fried also, refreshingly, touches on less well-known cases, as in his treatment of female mystics, such as Christine de St Trond from the early 13th century, who would whirl herself into unconsciousness ‘like a dervish’ in a state of self-induced ecstasy. Her trance-like states carried her ‘quite literally to new heights, as she would clamber into the rafters of churches and climb towers and trees, flirting with death’. Her dedication went way beyond the self-punishing rituals of the flagellants (or ‘flatulents’, as one of my students insists on calling them). Christine ‘tried to replicate the torments of sinners in Hell by putting herself in ovens, plunging into boiling water, having herself lashed to mill wheels and hanged on gallows, and lying in open graves’. The book is replete with vivid little life stories.

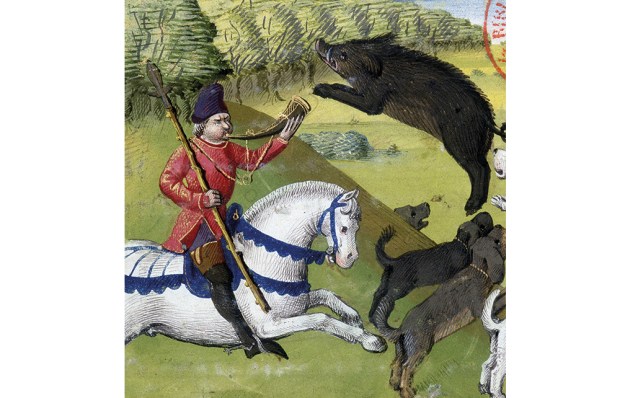

Fried covers much else in the realm of ideas on monarchy, jurisprudence, arts, chivalry and courtly love, millenarianism and papal power, all of it a rewarding read. Less successful is the rather perfunctory treatment of political history, where errata and outdated ideas creep in on military and political matters for the later medieval period. The book is a translation of the third German edition from 2009; only a couple of more recent titles have been thrown into the bibliography for this edition.

Fried successfully achieves his goal in rebutting modern, chronocentric notions of a ‘Dark Middle Ages’, though. The medieval period was, he argues passionately and convincingly, ‘more mature and more wise, more inquisitive, inventive and with a finer feel for art’, and its people ‘more revolutionary in their deployment of reason and their thinking’ than we give them credit for. Well, except perhaps for Christine de St Trond, swinging hysterically from the treetops.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £23 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in