In one of the more peculiar concerts that I have been to at the Royal Festival Hall, Vladimir Jurowski conducted excerpts from Das Rheingold in the first half of the programme, and Rachmaninov’s little-known opera The Miserly Knight in the second half. The idea, I gleaned from a pre-concert chat by the conductor and others, was that the first half would shed some light on the second, showing that although Rachmaninov, at one time an industrious operatic conductor, almost certainly never conducted Wagner, he was strongly influenced by him.

The point seems academic, unless you are interested in the minutiae of musical history. Anyway, the Rheingold excerpts failed miserably, on their own terms and as a portent. We began with the prelude, the famous depiction of the Rhine’s flowing. Jurowski conscientiously stuck to Wagner’s dynamic directions, as few conductors do, keeping the volume down to mezzo-forte. But in concert the result is oddly unstirring. We continued with the first scene, the Rhinemaidens teasing poor Alberich, and the interlude that follows. This 43-minute continuous epic segued into the descent to Nibelheim, complete with 18 tuned anvils, followed immediately by the ascent from Nibelheim, complete with 18 tuned anvils. Then came Donner summoning the storm, and the closing music with the male gods (no Fricka) singing their few lines: a recipe for incoherence and possibly for putting tyros off Wagner for life. Dramatically meaningless, musically incoherent, how can anyone now tolerate such an artistic crime?

The punishment that followed the crime showed that the neglect of Rachmaninov’s second opera is almost wholly deserved. Adapted from one of Pushkin’s ‘little tragedies’, it is hard to think of a drama, closet or otherwise, so unsuited for setting to music. It has some striking passages, especially the orchestral introduction, but Chaliapin, for whom it was composed, showed his good sense by turning it down. The singers were adequate, especially Peter Bronder as the Moneylender. Jurowski’s programming always shows that he thinks hard, but often to no good purpose.

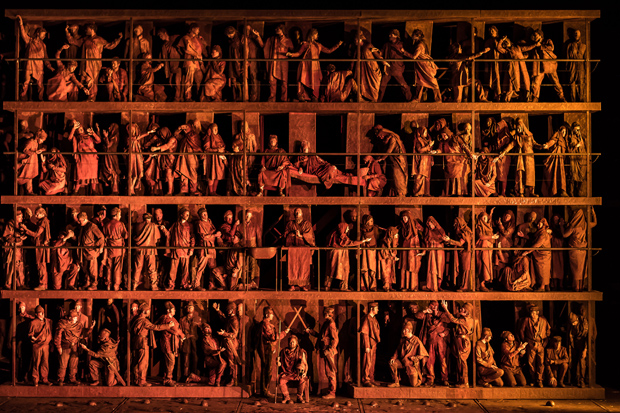

Opera North’s new production of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro (in the notes Jeremy Sams, the translator, tells us that he used to be keen on it being called Figaro’s Wedding, but now doesn’t mind. Surely the younger Sams was right?) is fairly good, but could easily be a lot better. The set designs, by Leslie Travers, follow the contemporary trend towards a dingy, down-at-heel Almaviva residence. That is no doubt right for the servants’ quarters, but to see the Countess singing her great second aria on a decaying staircase, which seems to take up most of the house, is saddening in the wrong way. And why is it raining hard throughout Acts 3 and 4, though only some of the characters either have or seem to need umbrellas?

The production, by Jo Davies, seems to be tilted, often heavily, towards making Figaro a farce rather than a serious comedy, with the interesting and deserved result that the moments of high comedy seem less funny than usual. The most obvious sign that Davies isn’t taking this masterpiece as probingly as she should is in the superficiality of the characterisation. It’s a relief not to see Don Basilio treated as an elderly clerical queen, but here he is nothing in particular, merely a moving Edwardian suit. Crucially, the Count, played by Quirijn de Lang, seems to be no more than a character from P.G. Wodehouse — bumbling, explosive, and with zero libido; he is like a dog, good at barking but not able vocally to express desire. That means that in all the crucial confrontations with Figaro, decently taken by Richard Burkhard, the erotic tension is lacking, which more or less spells disaster for the movement of the drama.

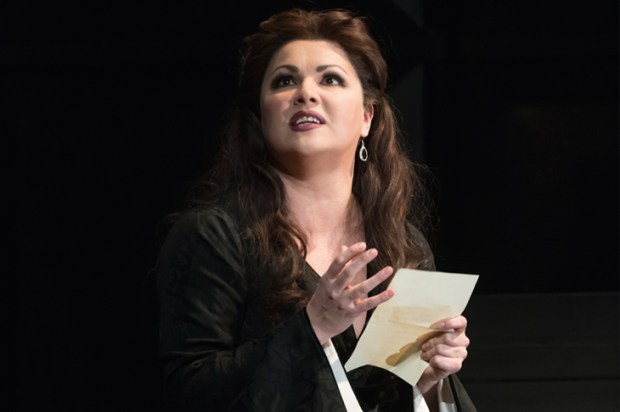

Ana Maria Labin’s Countess steadily improved throughout the evening, so that the Count’s plea for forgiveness and her granting of it were as moving as they should be. Silvia Moi’s Susanna is charming but indistinguishable from a hundred other performers of the role. The disaster is Cherubino, the tall but obstinately feminine Helen Sherman, bafflingly dressed to make sure no one could think she is a man.

The saviour of the evening is the conductor, Alexander Shelley. From the opening bars of the Overture onwards he showed an infallible sense of tempo; his balancing of the orchestra, and of the singers against the orchestra, is masterly — many woodwind details were new to me and added significantly to my internal sonic image of Figaro. And he reached his peaks of detailed but forward-moving musical drama in the sublime finales to Acts 2 and 4. My touchstones, Figaro’s melody when he complains that he twisted his ankle, built up in a few bars to a hymn; and the astounding passage in the finale to Act 4 where the madness briefly pauses and Figaro invokes mythic heroes to the accompaniment of solemn winds — these, for once, left nothing to be desired. Connoisseurs of Figaro should go for those alone; anyone who isn’t a connoisseur should go anyway.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in