The Paris World’s Fair of 1937 was more than a testing ground for artistic innovation; it was a battleground for political ideologies. The Imperial eagle spread its wings over the German Pavilion; the Soviet hammer swung above the Russian Pavilion; and the Spanish Pavilion unveiled Picasso’s shocking monument to the civilian dead of the bombed city of Guernica, raising the clenched fist of the Spanish Republic in the capital of non-interventionist France.

Not everyone was convinced by ‘Guernica’ as art. Anthony Blunt in The Spectator commended Picasso’s political gesture but dismissed the painting as ‘the expression of a private brainstorm’. Piqued on the artist’s behalf, the British surrealist Roland Penrose, who had seen the work in progress, arranged to have it exhibited in London at the New Burlington Galleries and the Whitechapel Art Gallery, where it attracted 15,000 visitors and £250 in donations for a food ship for Spain. In Paris the Spanish finance minister had compared the picture’s propaganda value to ‘a military victory on the front’: in London it furnished heavy artillery to the British avant-garde’s campaign against traditional realist art.

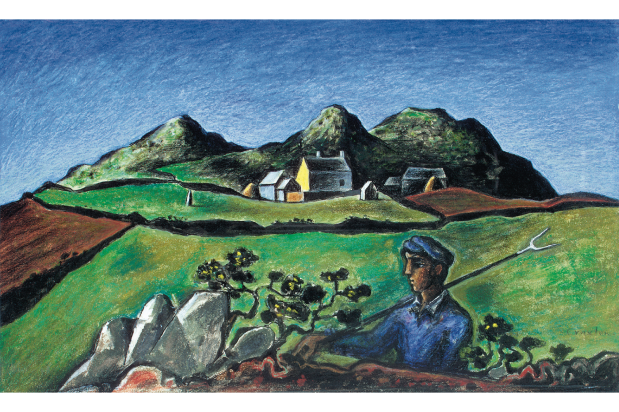

‘Guernica’ casts a long shadow over Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War, the first exhibition to examine this overlooked subject. On the Spanish side the show fields some sample Picassos — two ‘Weeping Woman’ images and ‘The Dream and Lie of Franco’ satirical prints. On the British side the big hitters are Henry Moore and Wyndham Lewis — batting half-heartedly for the nationalist team — but most of the names are less familiar, in keeping with Pallant House Gallery’s continuing mission of introducing us to modern British artists we don’t know, but should.

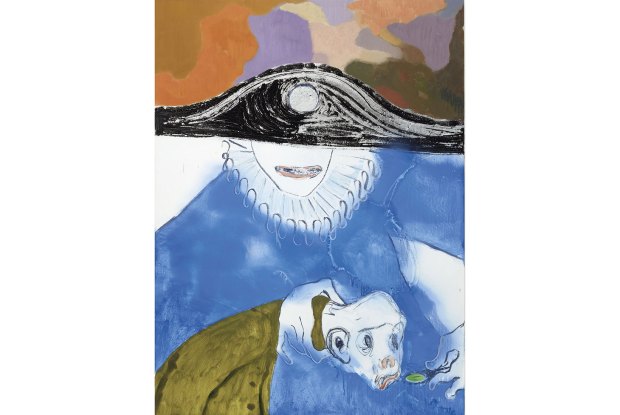

As the biggest contingent, the surrealists get a room to themselves. British surrealism was closely bound up with the Spanish Civil War, which broke out in July 1936, a month after the International Surrealist Exhibition opened in London, though to look at the work on show you’d never guess it — it’s all terribly English and polite. One doesn’t doubt the strength of their political convictions, but there’s a whiff of Owl and Pussycat whimsy about Julian Trevelyan’s description of James Cant, T. Graham, Penrose and himself marching in the 1938 May Day parade wearing Neville Chamberlain masks made by F.E. McWilliam and dancing the occasional ‘little minuet together, waving our umbrellas’. More problematic, the art pussyfoots around the issues. Viewed dispassionately with hindsight, Stanley William Hayter’s ‘Paysage Anthropophage’ (1937), with its female figure apparently dancing a cubo-surrealist flamenco, and Roland Penrose’s ‘Elephant Bird’ (1938), collaged from articulated sections of the Eiffel Tower, look more like style statements than revolutionary manifestos.

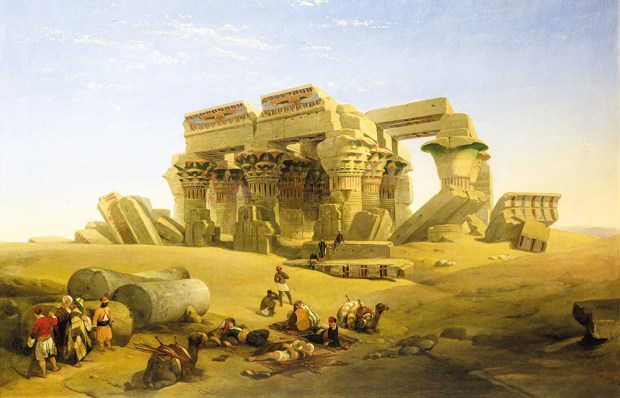

‘Guernica’ was too tough an act to follow, and the sensible artists in this show don’t try. Walter Nessler’s nightmare capriccio of London landmarks overshadowed by a giant gas mask, titled ‘Premonition’ (1937), conveys its chilling message — ‘We’re next’ — with realist clarity. Edward Burra’s dreamlike vision of cloaked clerical figures among classical ruins, titled ‘The Watcher’ (1937), is infused with a horribly sinister ambiguity — Burra was haunted by the memory of smelling smoke from a burning Madrid church on the eve of the war. But the most haunting ruins are John Armstrong’s shells of bombed-out houses, isolated against surreally clear blue skies with the scars of human habitation — stair runs, blackened hearths, blown-out windows, tattered wallpaper — standing witness to shattered lives. Armstrong’s five paintings, all from private collections, are the revelations of the show.

‘We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth,’ the Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durruti proclaimed at the start of the war. Too familiar with ruins from the first world war, Armstrong didn’t share Durruti’s optimism, but others did. The 32-year-old Felicia Browne joined a communist militia in Barcelona in August 1936, before the formation of the International Brigades, and became the first British casualty of the Spanish Civil War. Her deft sketchbook drawings of the ‘enormous cubic women’ in charge of the barrack kitchens are another discovery. Unlike her fellow communist and Slade contemporary Clive Branson, who later served with the International Brigades, Browne didn’t feel obliged to adopt a faux-naïve proletarian idiom to express her heroic egalitarian vision. Her drawings are unashamedly modernist but immediately legible. Too many works in this show have the furtive look of artistic examinations of conscience, but Browne’s conscience, like her graphic line, was clear. ‘When she drew she was content to draw as well as in her lay,’ the New Statesman critic wrote of her posthumous exhibition. ‘And as for her convictions — she showed them by dying for them.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in