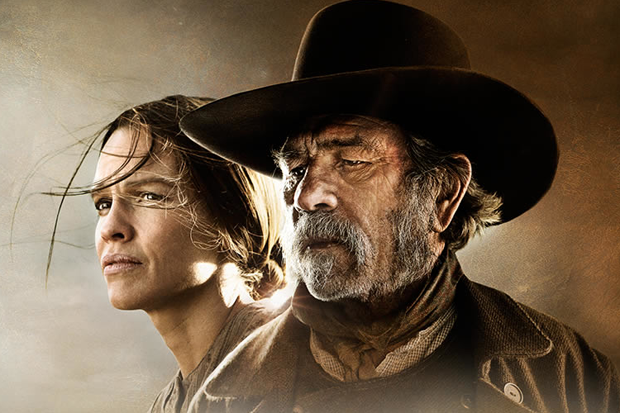

The Homesman, which stars Hilary Swank and Tommy Lee Jones and is set in the Nebraska territory in the 1850s, is being sold as ‘a feminist Western’, which is a bit rich. This is not a bad film. It’s modestly entertaining, in its way. And it does portray the harshness of life for the early women settlers. But feminist? When, at around the midway mark, it goes all John Wayne on us? ‘Oh please, don’t go all John Wayne on us,’ I begged the film. ‘Please be more interesting than that.’ But it was determined. And I suppose the clue was in the title all along.

This is not, ultimately, a story told through a woman’s eyes. It is told through a man’s eyes. And it’s not a story in which any woman’s character takes a journey. It is George Briggs who does that, as played by Jones who — and this may be just me — looks increasingly like a squashed Walter Matthau; as if Walter Matthau had been put in a compactor. Jones also wrote the screenplay (with Kieran Fitzgerald and Wesley Oliver, as based on the novel by Glendon Swarthout) and directs. So, nothing female in its provenance, although Jones has declared himself a ‘feminist’ so that is OK, if it is. Is it? A man can be a feminist sympathiser, certainly. But a feminist? A non-Jew can be against anti-Semitism, but Jewish? To be Jewish, don’t you have to feel what it’s like to be a Jew, every single day? To be feminist, don’t you have to feel what it’s like to be a woman every day? Just putting that out there, for your consideration, as they say.

At first, the film does focus on its female protagonist, Mary Bee Cuddy (an excellent Swank), who, in the opening scene, is viewed trying to plough her patch of unforgiving land against a landscape that appears just as unforgiving: flat, wide, vast, treeless. Later that day, she makes supper for a neighbouring farmer. She is lonely, it becomes apparent, and wants children and a home. She proposes to him, and he rejects her, mostly on the grounds that she is too ‘plain’. Other men will later tell Mary Bee she is too plain, too. So, yes, it is one of those films in which we are expected to believe the lead actress is plain, even though she evidently isn’t, but the alternative might have been to cast a plain actress, and that would never do. It would break Hollywood or something. It might even be feminist.

We are in no doubt as to the bleakness of the life, though. Children die, the weather is extreme, husbands are toxic, babies are thrown into latrines, and it has sent three of the local women mad. These women, decree the menfolk, must be taken back east, and it’s Mary Bee, who has far from lost her mind — ‘You are as good a man as any man,’ she is told — who volunteers to take charge of them for the five-week journey, but she does not travel alone. She hooks up with Briggs, an army deserter with a taste for whiskey, whom she saves from hanging but only on condition he accompanies her. The insane women are tied in the back of a wagon, and don’t contribute much from here on in; are never fleshed out, or allowed to speak for themselves, while Mary Bee, unlike Briggs, isn’t given any back story. What brought her to Nebraska, when she did not have to follow a husband? Why does she seem wealthier than the other members of her community? How come she can leave her farmstead for all those weeks? We’ll never, ever know.

Once they hit the road, the film employs the trusty western structure of the epic journey where dangers must be faced — Briggs must see off Indians, obviously, John Wayne-style — and also employs the classic ‘odd-couple’ dynamic. Do Mary Bee and Briggs hate each other at the outset? They do. Do they have opposing personalities? They do. She is morally upright, God-fearing, compassionate, whereas he is Rooster Cogburn, basically. And it’s hard to know what exactly the film is getting at, as its tone shifts all over the place. It is told episodically, and some of the episodes are, frankly, quite bizarre. This includes Briggs’s fondness for breaking out into a capering little jig (what’s all that about?; I cringed) and wreaking the most sensational vengeance on a hotelier who refuses to supply the travellers with refreshments. (The hotelier is played by James Spader with the worst Oirish accent you ever did hear, and although he is on the poster, he is only in this for two minutes, tops. Same with Meryl Streep, if you’ve been wondering why I haven’t mentioned her yet.)

But the worst occurs when Mary Bee does something that not only seems way out of character, and undeserved, but also shifts the focus entirely on to Briggs, and the effect Mary Bee Cuddy has had on his life. That’s it, it appears. This is what we’ve been interested in for the past two hours. So The Homesman has women in it, but a ‘feminist western’? No.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in