‘I just stay here and do my thing,’ David Hockney told me soon after I arrived at his house and studio in Los Angeles this August. ‘I’m not that interested in what happens outside. I live the same way as I have for years. I’m just a worker.’ Hockney has been labouring prodigiously for more than 60 years now, since he entered Bradford School of Art at the age of 16.

‘There is something inside David,’ his assistant Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima noted, ‘that drives him to make pictures.’ In the summer of 2013, after a series of disasters — including a minor stroke and the terrible death of a young assistant — Hockney moved back to California after a long period of working in Bridlington. It was a dark period. Nonetheless for the past 12 months Hockney has been on an intense creative roll, which has included painting a cycle of more than 50 portraits, plus another series of groups of people in conversation, dancing and playing cards, and, in the past few months, the invention of a novel variety of digital photographic collage. Examples of the last two series are currently on show at the Pace Gallery, New York, in an exhibition entitled Some New Painting (and Photography).

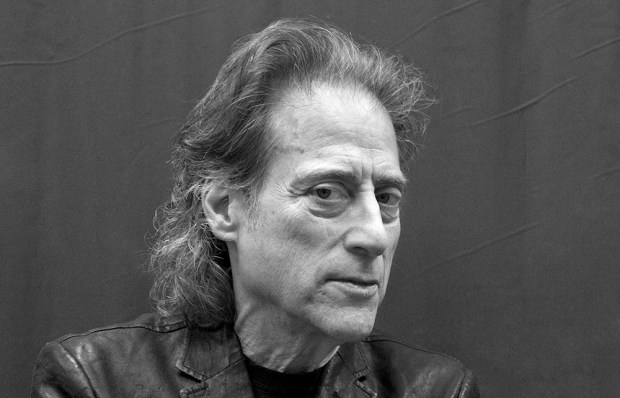

This month a film is released that chronicles this immensely productive life to date. Directed by Randall Wright and simply entitled Hockney, it is itself a kind of collage, cut together from an archive of 19 films made by Hockney himself since the 1960s about his own activities along with new footage of the artist and friends, old and new. The result is somewhere between biography and autobiography, in cinematic terms. Hockney pops up, non-sequentially, at various ages sporting a wide variety of outfits, hairstyles and colours; while others who have known him at various stages since his childhood contribute their own memories.

In the film Hockney makes a point that he also made to me in conversation. ‘I spent most of my life living in bohemia, and I expected to spend my whole life there. But bohemia has almost disappeared.’ This strange death of bohemian England — and everywhere else, for that matter — was a topic of discussion while I was staying with Hockney this summer to work on a book project. We did not really come up with a full explanation, although we speculated that a more earnest zeitgeist and the disappearance of cheap rented property both played a part.

In any case, Hockney was always an unusual bohemian. He moved from London to Paris, partly because friends persisted in dropping in at his studio, chatting and staying for hours. Then the same thing happened in Paris, which was one reason why he ended up in LA and subsequently, for a decade up to last year, in East Yorkshire. He wanted peace and solitude to work.

Though he is a famously eloquent man and has been a public personality for much of his life, Hockney spends a great deal of time thinking and reading. ‘I sit in the studio a lot,’ he says, ‘just taking in the pictures.’

However, the fact that he was a citizen of this informal community bohemia — a state of mind, if not a political entity — explains some aspects of his life. When people ask him whether it took courage to be gay in the 1960s, he demurs. ‘I was living in bohemia, and bohemia was a tolerant place.’

However, courage clearly is a crucial element in Hockney’s approach to life. In the film, he describes how his father — a pacifist and vegetarian in wartime Bradford — advised him not to pay too much attention to what the neighbours thought. It was a lesson he learnt well. Hockney has always had the nerve required to be himself. As a teenager, he wheeled his paints and materials around the streets of Bradford wearing a dandyish costume of his own devising: proudly, even defiantly, an individual and an artist.

Subsequently, like his older contemporaries among British figurative artists, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, he had the audacity to ignore the dictates of art fashion. ‘Nobody’s taking any notice of the avant-garde any more,’ Hockney notes. ‘They’re finding they’ve lost their authority.’

He’s probably correct about that. For the past decade or two, it has been hard to say what the cutting edge might be. In a world without rules it is impossible for anyone to break any. ‘They thought they would get authority by damaging the other, earlier establishment,’ Hockney suggests. ‘But by doing that you damage all authority.’

Hockney himself has never been a member of the avant-garde, or any other team; more an expeditionary force of one, determinedly pursuing his own explorations. The centre of his interest has always been what he calls ‘the depiction of the visible world’. And his crucial skill has been drawing, which he was thoroughly taught at Bradford and practised late into every evening, thus developing an extraordinary virtuosity.

He laments the neglect of drawing in recent art education. ‘People had been drawing for 40,000 years, and they gave it up in 1975. It’s almost funny. But they couldn’t give it up really. You can’t: it’s always back to the drawing board!’ By that, he means that any new way of seeing the world will have to be produced by the human eye, heart and hand, working together. And this applies as much to new types of photographic imagery as it does to paintings.

At the end of Wright’s film, Hockney wanders out of his studio in the hills above Los Angeles to the garden and swimming pool (a miniature world, in which even the bricks in the wall are painted in his own colours). He is, the commentary suggests, still searching.

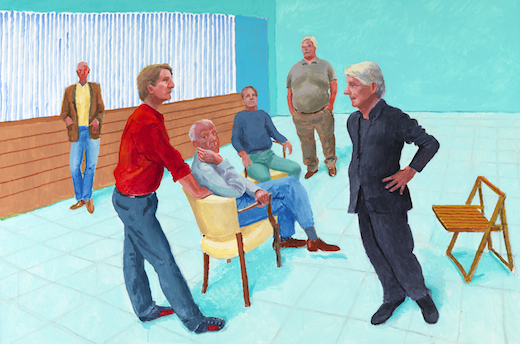

Since that sequence was filmed, he has not only sought but found new artistic directions. His new group paintings are a novel way of resolving a dissatisfaction he has long felt with traditional single-point perspective. This, Hockney argues, is untrue to the way human beings see. ‘When my eye moves, the perspective alters according to the way I’m looking, so it’s constantly changing; in real life when you are looking at five people there are a thousand perspectives.’

The recent group of paintings deals with this problem by including multiple viewpoints, so a figure will be viewed from various angles — just as in life if standing in a room with someone, you’d look down to see their feet and then across at their face.

One day, when we were sitting in the studio just before lunch, Hockney was musing that he might be able to produce the same effect by taking multiple shots of people and the room they were standing in, then editing them together on his iPad. ‘In fact,’ he suddenly said, ‘I think I’ll do it now!’

So he did, producing the first of a stream of works that appeared at the rate of one every day or so over the following weeks. They are in a way an updated, digital version of the celebrated photo-collages he made in the 1980s. In those, he made a mosaic of hundreds of shots taken from differing positions creating a sort of photographic cubism.

What’s the subject of these brand-new pictures? ‘The space between where you end and I begin, which is the most interesting space of all. It’s far more interesting than outer space. It’s all about me, looking. That’s what any picture is, an account of looking at something.’

It’s what David Hockney has been doing all these years, and the fascination both of looking and of making pictures of what he sees has only intensified with time. ‘I’ve always been interested in how we see, and what we see. I’m 77 now but I don’t bother about that.’ If anything he seems to be speeding up.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

‘Some New Painting (and Photography)’ is at Pace Gallery, New York, until 10 January 2015. ‘Hockney’, directed by Randall Wright, goes on general release on 28 November.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in