While Mrs Oakley was patrolling the aisles in Waitrose one day recently, I slipped off into my local betting shop. There, too, fresh from the pub, was Mr Knowall on the day that we learned that the former champion jockey Jamie Spencer, at only 34, intended to retire. ‘Effing retiring at 34,’ Mr Knowall told the Coral clientele. ‘It just goes to show these jockeys are all paid too much.’

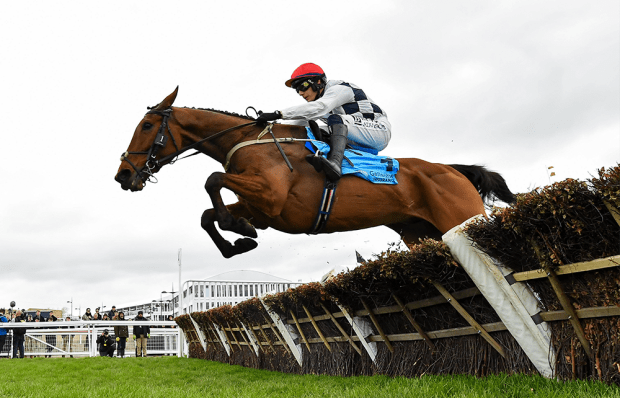

There was no point in arguing with beer-fuelled ignorance, and of course Jamie Spencer won’t quit the saddle as a pauper. He has been in the elite band whose talents are so valued that rich owners fly them around the world to employ their services. He deserves to be taking a few nice nest eggs into ‘retirement’ with him. What the Knowalls forget is how few jockeys live at that level. Yes, stars such as Frankie Dettori and Richard Hughes on the Flat, or Tony McCoy and Ruby Walsh over jumps, do well, but the majority of those who risk life and limb in the only sport apart from motor-racing in which the participants are regularly followed by an ambulance are bumping along the bottom financially.

I checked a few facts with Dale Gibson, formerly a respected Northern-based jockey and now the industry liaison officer for the Professional Jockeys Association. Flat jockeys earn £118.29 a ride and the jumps boys, facing a greater risk of injury, get £161.51. Fine for a top jockey with five or six rides on a card. Not so hot for the grafter driving up to Musselburgh for a single ride on a no-hoper. Nobody pays his petrol expenses and he may well have driven 50 miles in another direction at 5 a.m. to ‘ride work’, educating horses for a trainer who won’t pay him for doing so in the hope of a future ride or two. He pays 10 per cent of his fee to the agent who booked his ride, 10 per cent to the valet who looks after his kit, and insurance payments on top of that. Gallingly, if a trainer pulls his horse out of a race at the last minute there is in Britain (unlike Australia) no compensation for the jockey who has travelled to ride it.

OK, say the likes of Mr Knowall, but what about the 10 per cent of prize money jockeys collect? ‘That’s a misconception,’ says Dale. ‘They haven’t had 10 per cent since 1972. For a win it’s 6.9 per cent on the Flat and 8.5 to 9 per cent over jumps. And for a place it’s only 3.5 per cent under both codes.’ But aren’t some jockeys given ‘retainers’ to be available regularly for an owner or stable? Those, says Dale, are now a rarity. For example, Paul Hanagan, the former champion jockey, had never had a penny by way of a retainer until he went to work for Sheikh Hamdan last year.

I chose a typical racecard at Beverley and totalled the first place prize money. It amounted to £26,660: 6.9 per cent of that comes to £1,840. There were 26 jockeys riding at the Yorkshire track that day of whom 14 had only a single ride. So nobody was going to go home rich. When I looked through the list of last season’s Flat riders, 75 had ridden only a single winner.

Take away the top ten, says Dale, and a median jockey is earning about £20,000 a year. Better than some jobs, it is true, but riskier and Dale Gibson puts it into perspective. The average premiership footballer earns £20,000 in a week.

Becoming a jockey is a career choice and the rewards for the top few can be spectacular. But most make sacrifices to live that life and impose them on their families. Of those who begin jockey training courses only 10 per cent complete their apprenticeship by ‘riding out their claim’ (i.e., riding enough winners to lose the probationers’ allowance of 7lb, 5lb or 3lb when competing against those more experienced). It then gets even tougher without that added incentive for trainers to book the talented ones: half of those who do ride out their claim drop out within two to three years. Only 5 per cent of would-be jockeys, says Dale, make it to a ten-to-15-winners-a-year career.

It isn’t all bad news. Thanks to the work of the Professional Jockeys Association, the BHA and the racing schools’ jockeys receive much better training than they did 20 years ago, better medical help and insurance, better nutritional advice and better life coaching. But for many the economics remain grim and in a sport built around gambling that is an obvious risk to its integrity. If a jockey whose career is in decline is offered, say, £1,000 by an unscrupulous manipulator to make minimum effort in a race he probably won’t win anyway you can see the temptation compared with a return of no more than £50 for a day’s work and a 200-mile drive. Filling in his betting slip, even Mr Knowall might acknowledge the implications of that.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in