I am nothing if not patriotic. Like most Americans, I am convinced that mine is the freest, most beautiful country on earth. But I cannot pretend to be happy that two of us have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

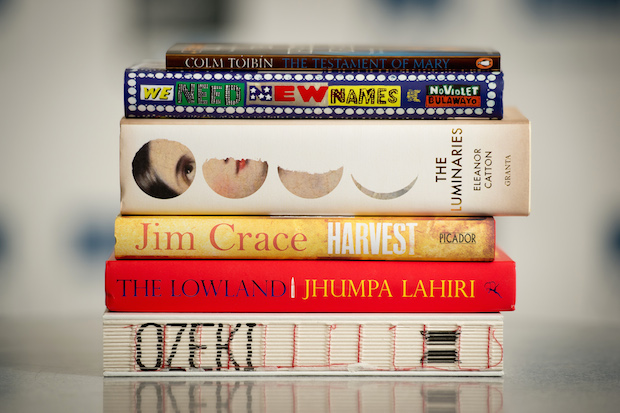

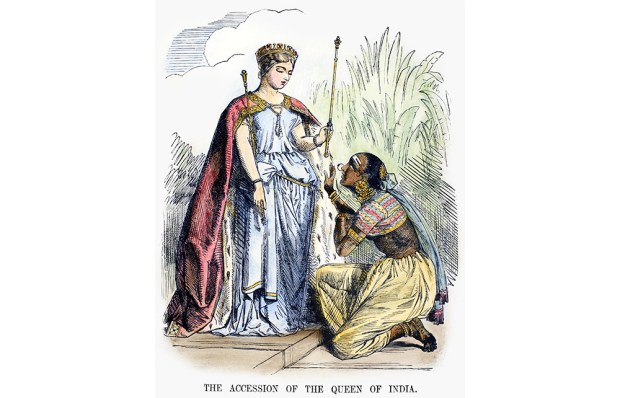

When it was announced earlier this year that novels written by Americans — in fact, all novels written in English and published in Britain — would now be eligible for the award, I dismissed the news as a harmless gimmick. Now I am not so sure. Behind the fair-play, hands-across-the-border niceness of the committee’s gesture, I sense something else: masochism. The best evidence of this is a piece that ran last week in — where else? — the Guardian in which a panel named 15 American novels that ought to have won the Booker in their respective years of publication. Here we are only a few weeks into the plus-Americans Booker season, with the announcement of the winner nearly a month away, and already more than a dozen of Britain’s literary bigwigs are prepared to cede the award’s entire history to foreigners, as if Her Majesty’s subjects have only ever been up to facing the transatlantic competition on off-years.

Perhaps I am taking the whole thing too seriously. After all, the Booker, or ‘Man Booker’ as its present corporate sponsor insists (by which logic one should refer to the ‘McDonald’s Olympic Games’ or the ‘Adidas World Cup’) has not always been a reliable index of artistic merit. We all have our favourite example of the judges’ shortsightedness; mine is Money, which failed to make the shortlist in 1984, losing out to a nice lyrical romance by Anita Brookner and one of David Lodge’s funny but indistinguishable campus novels.

Of course, much the same thing could be said for any award. In my lifetime the Nobel Prize for Literature seems to have gone only to feminist science-fiction pioneers and unknown Chinese dissidents: good writers, I’m sure, but not really on shoulder-to-shoulder terms with Kipling or Bernard Shaw or even the eccentric Scandinavians who used to win every other year or so.

Whatever its shortcomings, the Booker has given well-deserved attention to many excellent novelists over the years. Its selections have usually been representative of a certain approach to the novel. Kingsley Amis and Penelope Fitzgerald and poor forgotten old P.H. Newby wrote books that, whatever else might be said for them, belong to a distinct tradition of British fiction. It is the tradition of the five Ms: morals, manners, money and marriage written about by (usually) middle-class novelists. It is impossible to imagine Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont or Quartet in Autumn being nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for the same reason that it comes as no surprise that Gravity’s Rainbow was rubbished in this paper or that Infinite Jest was derided even in the pages of the London Review of Books.

British and American literature began to go their separate ways long ago. The American novel has long been dominated by ethnicity and geography — race and space. Instead of a single cohesive national tradition, we have a handful of regional literatures: Hawthorne’s autumnal New England, Twain’s wild frontier, Flannery O’Connor’s haunted South, Saul Bellow’s Chicago, Edith Wharton’s and Ralph Ellison’s very different New Yorks. Our best novelists tend to come either from patrician families or from poverty.

It is not only America’s heterogeneity that has set her apart. British and American novelists responded differently to the advent of what used to be called ‘High Modernism’. When British writers read Ulysses, they reacted either like Evelyn Waugh, who dismissed it as ‘gibberish’, or like Anthony Powell, who saw it as a curiosity and compared it to The Anatomy of Melancholy. Americans, on the other hand, tended to see the book as a challenge, even as a new paradigm.

Meanwhile would-be British novelists continued the century-plus-old tradition of apprenticeship in Fleet Street, while young Americans signed up for graduate courses in creative writing. One has to think that this takes us very near the crux. Whereas up-and-coming Britons have long worked on deadlines to write amusing prose that hundreds of thousands of people pay to read, at least two generations of Americans have spent their formative years in an atmosphere of hermetic leisure producing endless ‘drafts’ for an audience of professors who are paid to look at their work rather than the other way round. One group has no choice but to entertain; the other has no incentive to do so.

This, I am glad to say, is beginning to abate. Things are beginning to look up, not least because more and more Americans are looking to British models for inspiration, especially in comic fiction. You would be hard pressed to find a 20- or 30-something scribbler in this country unfamiliar with Paul Pennyfeather. If Jonathan Franzen would write a new book every two or three years and trust in his Trollopean instincts for domestic comedy rather than try to emulate Don DeLillo, we would have a very great novelist on our hands. In the meantime, excluding us from the Booker would do us no harm, as we continue with our MFAs and our million-dollar grants to established writers.

By the time you are likely to read this, Alex Salmond’s referendum will have been held in Scotland. President Obama and I are hoping for a ‘no’ vote. Whatever the outcome, it is clear that British identity needs shoring up. Literature is the place to start. Philip Hensher and many others have written wonderful books this year, and America is in the midst of a P.G. Wodehouse revival. Right now you have a literary trade surplus on your hands. Don’t squander it. Find some cultivated millionaire to reboot the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, shamefully suspended since 2010, and give it to Julian Barnes. (He is too old, but some rules ought to be changed.) To rephrase Gordon Brown, ‘British prizes for British writers’.

Atavism isn’t what I’m prescribing: just a nice collective dose of national self-esteem.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in