When I was first learning about classical music, 50 years ago, the scene was more streamlined than it is now. Beethoven was king, with Brahms and Mozart next in line, and Haydn slowly establishing himself. Mahler was the new kid on the block; Bruckner was largely unknown and mistrusted. If one wanted the full symphony orchestra experience in late romantic music, it was to Tchaikovsky that most promoters turned. Tchaikovsky cycles, Beethoven cycles, Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies, Mozart’s last three symphonies were the way to guarantee a crowd, with general knowledge of all Beethoven’s music — string quartets, piano trios, Lieder — at an all-time high.

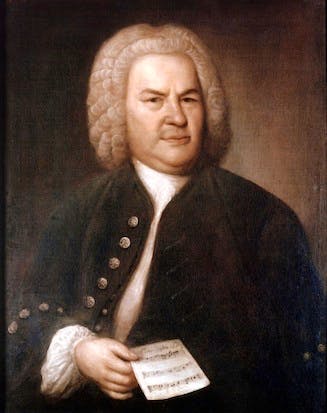

Now Bach is king. In fact, he is more than king: he is pope and emperor rolled into one, speaking for sacred and secular music enthusiasts alike. Never before has a composer from the past so completely dominated the classical music scene. Where Beethoven was once found to be manageably romantic, his deafness and tousled hair playing into the persona, Bach is seen as a superman, an Übermensch, whose impeccable technique delivered every time. We like that sort of security now. There has been a shift, from admiring flamboyance tinged with a little danger, to needing rock-solid reliability. Bach is the antithesis of boom and bust. We can feel safe with him.

How has this move back in time been possible? Part of it can be explained by the triumph of the early-music revolution. Fifty years ago there was only one kind of symphony orchestra, the kind that played everything. Now there are two kinds: those that start with the late romantics and go up to the present day; and those that tackle everything up to the late romantics, with a crossover period between the two types around Beethoven. The big sound of the modern-instrument orchestra was always enjoyed as much in Beethoven as in Tchaikovsky, and still is by many non-purists, but it never did very well in Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, or in accompanying the B Minor Mass. Bach has been the main beneficiary of the original-instrument revolution, which fuelled his advance like nothing else. For those who liked his organ music, for example, there was little need for reappraisal, since organs have essentially remained unchanged. The same can be said for his other keyboard writing, the harpsichord having been established for a long time now. Even the way Bach is sung hasn’t changed that much. Bach’s current status has been made possible by playing his orchestral writing on instruments he would have recognised.

For some reason this hasn’t worked quite so well for Handel. He was once a king with many courtiers — as long as one didn’t mind one’s choruses sounding heavyweight. Now he has been eclipsed. A boast at the Proms this year is that for the first time the series will include both the John and the Matthew Passions of Bach. There is almost no Handel of any description. Once upon a time, Messiah was found to contain all the variants of sublime truth an ordinary person could possibly have use for; now it is Bach’s Passions. Fifty years ago, performances of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis were standard; now it is Bach’s B minor Mass. When it comes to ultimate things, it has to be Bach.

There is a danger in all this, as anyone who has studied Shakespeare will know. Frank Kermode once listed the special-interest groups he had come across, largely in the US, who had appropriated some aspect or other of the bard’s work to justify and illustrate their extreme positions. Apparently, if you look hard enough in Shakespeare you can find cogent arguments for and against abortion, lesbian relationships, S&M and a host of other contemporary troubles. The problem for Kermode, not to mention Shakespeare’s reputation, is that Shakespeare has been so mindlessly idolised that he is beyond criticism, an icon of perfection that makes him not just a king but a god too. This is as unhealthy as it is ridiculous. We mortals are indeed foolish: John Eliot Gardiner’s recent book on Bach — Music in the Castle of Heaven — shows clearly just how mortal Bach was.

Ben Jonson complained that the fluency of Shakespeare’s language should have been curbed (‘would he had blotted a thousand’ was his response to hearing Shakespeare praised for never having blotted a line). If that view became more general, a lot of people in the theatre industry would have to do some radical rethinking. There is plenty of room for a book on Bach that points out, among other things, that he could be a tedious old windbag. It would have the merit of saving him from becoming a god.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in