There’s a problem, as we all know, with female roles in the theatrical canon, and it reaches all the way back to the Bard. Shakespeare’s women lack the richness and variety of his male characters. Modern theatre practitioners have tried all kinds of ploys to correct this imbalance. Next month the RSC launches a season of dramas, Roaring Girls, written during Shakespeare’s lifetime and featuring women in pivotal roles. This is bound to reopen the question of Shakespeare’s approach to women and their subordinate position in his work.

It’s easy to argue that Shakespeare’s art simply reflects his habitat. Wealth, freedom and influence were the preserve of men, so he tended to leave women on the sidelines. As a dramatist, he was unusually fixated with power and kingship, and this led him to explore the male principle at the expense of the female. He was also, I suspect, aware that the convention of all-male casting undermined the credibility of female characters on stage. He could dash off a terrific role for a woman but the part would be played by a heavily rouged choirboy in his early teens. The craftsman in him must have recoiled at the absurdity of a gangly pipsqueak impersonating a tragic heroine. And yet this doesn’t fully explain why a writer who built a play around a Jew, and another around a Moor, never did the same for a woman.

Even where a female is given a title role, she has to accept second billing. Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, Troilus and Cressida. A script like The Merry Wives of Windsor suggests an all-female focus but the largest part belongs to Falstaff. And Shakespeare’s women operate within a remarkably limited emotional landscape. Broadly, there are two categories: the violent maverick and the simpering martyr. The mavericks include Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth, Goneril, Regan and Juliet. The martyrs, who form a far larger sorority, include Cordelia, Desdemona, Ophelia, Lady Macduff, Hermione (in The Winter’s Tale), Lady Anne (in Richard III), Katherine (in Henry V), Calpurnia (in Julius Caesar), and many others. Only one female character, Kate in the Shrew, straddles both categories. And her descent from rebel to victim is among the most troubling journeys in all drama. Hamlet’s mother Gertrude is an enigmatic exception. She may be a bloodstained schemer or an innocent dupe but the audience isn’t permitted to know which. ‘Leave her to heaven,’ says the Ghost, effectively closing down the investigation into her complicity in the murder of her husband.

We might also identify a subcategory, the plucky verbal pugilist, such as Beatrice in Much Ado and Portia in The Merchant. Yet they feel like wish-fulfilment fantasies dreamed up by a blokeish gadabout who enjoyed the company of varsity wits. Both characters are combative literary swordsmen in frocks rather than independent female creations. In Portia’s case, she only reaches her full potential after disguising herself as a man.

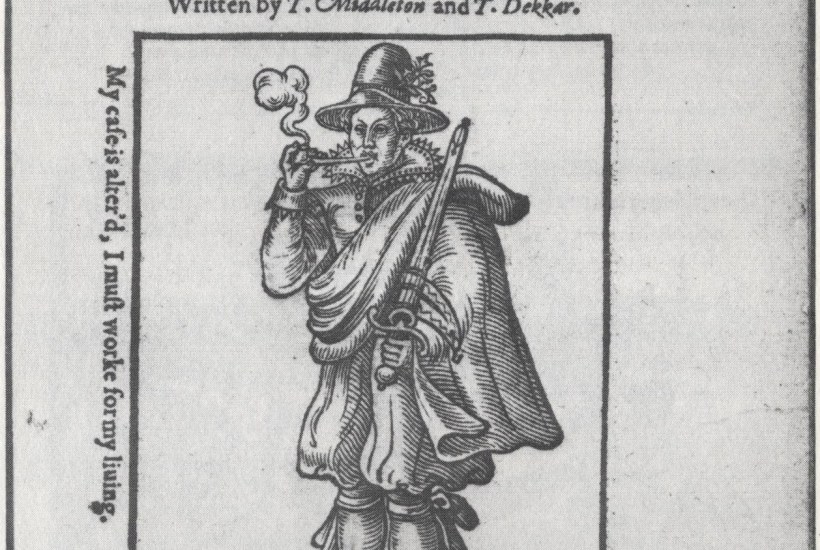

The Roaring Girls season throws light on Shakespeare’s world and reveals that the women of his day were not just trophy brides or obedient house slaves. The season takes its name from The Roaring Girl, by Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton, which celebrates the life of an historical character, Mary Frith. The writers gave her a catchy new nickname, Moll Cutpurse. The real Mary Frith was a notorious and rather attractive Elizabethan outlaw, who dressed as a gentleman (breeches, sword, helmet, pipe), and earned her living by thieving, passing stolen goods and procuring whores for rich clients. She inspired at least one other play, The Madde Pranckes of Merry Mall of the Banckside, whose authorship is unknown. She lived in some style with three maids, an aviary of parrots and a collection of pedigree mastiffs.

The play treats her as an endearing grotesque rather than as a threat to the social fabric. She first appears as an acquaintance of Sebastian, a high-born roisterer, who wants to marry his sweetheart Mary, but fears his father will insist on too large a dowry. Sebastian pretends to fall for Moll Cutpurse in the hope that this scandalous liaison will open his father’s eyes to the relative merits of Mary. Sebastian’s father commissions a spy named Trapdoor to gain Moll’s confidence and destroy her. This scheme fails and the play finishes on a note of harmony and reconciliation. What’s most striking is that Moll, who represents sexual licence and social chaos, reaches the end of the play with her life intact and her freedom preserved. She also retains her moral dignity.

The play is bound to disturb our received view of Shakespearean society as repressed and deeply conservative. A more traditional approach to errant womanhood is on display in the frontispiece to Arden of Faversham, another lesser-known work in the RSC series. Thomas Arden, a bullying landowner, is married to the unfaithful Alice, who conspires with her lover Mosby to murder him. They hire two bungling thugs to commit the crime but after Thomas’s death their guilt is discovered. Alice and Mosby are tried and executed. The publisher prefaces this ‘lamentable and true tragedie’ with a paragraph of stern rhetoric:

‘Wherein is fhewed the great mallice and difcimulation of a wicked woman, the unfatiable desire of filthie lust and the fhamefull end of all murderers.’

And yet the play’s message is more ambiguous than this preachy curtain-raiser suggests. Thomas is portrayed as a cruel and abusive husband who steals land from a neighbour in the opening scene. He’s a brute, in other words, and he deserves his come-uppance. The play’s director, Polly Findlay, believes the censorious preface is a piece of ‘window-dressing’ inserted by a canny publisher who wanted to profit from a bawdy comedy without appearing to outrage public morality.

She likens the play, which dates from 1592, to a Coen brothers movie. ‘The boundaries between comedy and darkness are hard to define. It’s a study in extreme conduct with the characters operating at the limits of acceptable behaviour.’ She has no doubt that the wayward Alice, who prizes true love over marital obedience, is the most engaging character. ‘It’s her tragedy.’

So here is a drama, performed in London during Shakespeare’s early manhood, which features a complex, powerful woman in a dominant role. Could he somehow have missed this artistic example? Not a chance. The bungling murderers hired by Alice and Mosby are named Black Will and Shakebag. The likelihood is that Shakespeare not only acted in the play but had a hand in its authorship, too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

The RSC’s Roaring Girls season — The Roaring Girl, Arden of Faversham and John Webster’s The White Devil — runs in rep at Stratford from 9 April to 4 October.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in