If a time traveller were to arrive in our world from, say, 1514 — a neat half-millennium away — what single feature would strike them most? What could they use on their return to try and explain the sheer weirdness of the future? A crowded mega-city? A hospital? An international airport? A computer? What about this — a container ship, a fifth-of-a-mile of steel transport travelling thousands of miles across unknown oceans filled with 150 tonnes of New Zealand lamb, 138,000 tins of cat food, 12,800 MP3 players and any amount of the paraphernalia for which the frenetic people of the 21st century work so hard to be able to afford?

In fact, you don’t need to come from the Tudor period to be amazed by the scale and extravagance. It is a strange version of a traditional marketplace that sends a ship to another continent to deliver milk and cheese, only to fill up with milk and cheese for the journey home, or to unload 300 tonnes of German timber to forested Canada, along with five tonnes of Polish grass and moss and 350 tonnes of seaweed from the East African coast.

Horatio Clare, in his acutely observed and surprisingly moving book, recounts two journeys on Maersk container ships. Maersk itself, a Danish company, generates an annual revenue of $60 billion, only slightly less than Microsoft. Clare sails first on the Gerd Maersk, a slick, newish carrier capable of holding 9,000 20-foot containers. He travels from Felixstowe to Los Angeles — with an interlude flying from Egypt to Singapore as the ship’s insurers will not accept the risk to him from Somali pirates. The second voyage is from east to west, from Antwerp to Montreal, on an older, smaller and much smellier ship, severely tested by an Atlantic storm.

Clare gives an extraordinary picture of these ocean-borne machines — the engine room, the bilges, the empty covered decks the crew use for sport, the intricate wharfside manoeuvrings. Everything about the ships and their management is unusual, even the dangers. Piracy is one of the few instances when international shipping enters public consciousness. Other risks are less obvious — fire is more feared than typhoons, and seamen face a very real threat from fellow crew members (news comes through when Clare is at sea of another Maersk ship where a crewman stabbed two of his shipmates to death). Clare asks one of the skippers what he would say to his own son if he chose to go to sea: ‘I would warn him about loneliness … about isolation.’

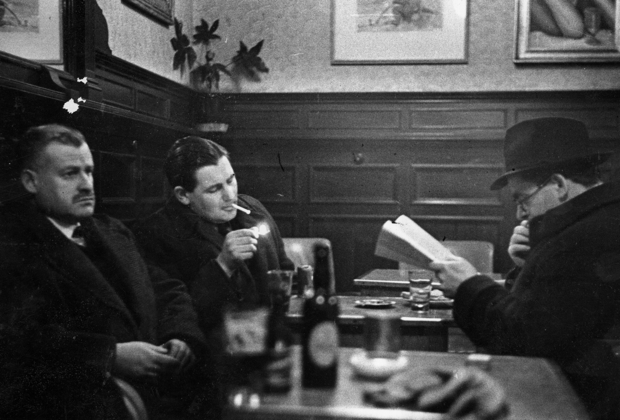

However intriguing the mechanics of maritime trade are, it is the people that emerge most strongly from Clare’s time on board. Most are Filipinos, who make up a third of the world’s seafarers. There is little time for talk — recently ships have become less social places: the crew perform their tasks with absorption, then disappear to their cabins to watch DVDs. Meals are often eaten in monkish silence and the bars have closed: Maersk banned alcohol on their ships in 2007. But as the weeks pass and the author observes his shipmates, some real characters emerge, distinct in their habits, their enthusiasms and their yearnings.

Clare’s writing everywhere is of the highest order, assured, probing and alert. But it is his ability to convey the strange effect on the human spirit of being at sea that raises the book above the ordinary. Haunting his pages are the ghosts of Melville and Conrad, each of them masters of the quiet peculiarity of sea-shaped men. Many of Clare’s portraits have the same appeal — the drily humorous Captain Larsen on the Gerd, with his passion for model trains, and the ‘mighty pathos’ of Captain Koop of the Maersk Pembroke. At the height of the Atlantic gale, Clare watches Koop on the bridge, facing the storm: ‘And so, alone, he gazes forward, always forward, a solitary figure overseeing his old machine and the violent desolation he has sent her into.’

As he watches the mariners at work, Clare senses a common trait: a certain self-possession, a kind of muted ‘greatness’. Theirs is not a job that is celebrated, nor even thought about very much by us who nonchalantly consume the goods they transport. Those who live and work at sea, who know their ships well enough to navigate them through its perils, can only be admired. The sea is bigger and more powerful than anything on land. Seamanship requires its own set of physical skills, arcane knowledge and langauge, and a level of constant battle-ready vigilance. That is one thing our Tudor time traveller would understand.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.99. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in