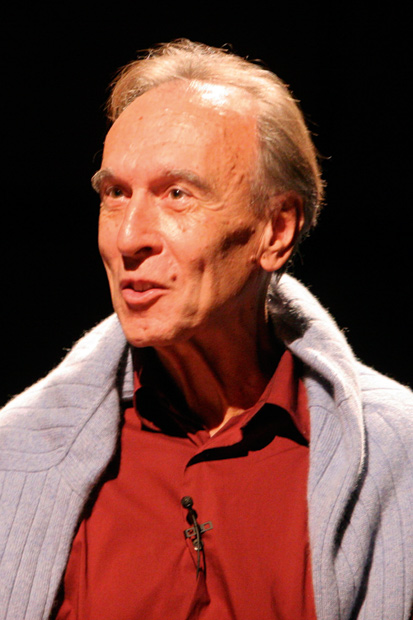

‘Have a look at this,’ says Daniel Harding, goggle-eyed, between mouthfuls of salmon. The pictures on his smartphone show Claudio Abbado, one of his mentors, conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in Schumann’s Scenes from Faust, a work that gets closer to Harding’s musical personality than any other, which he has just recorded with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, and which he will conduct in Berlin in December. ‘Doing his prep’, you might call it.

If ever a conductor was a child of his time it is Harding, who, at 38, remains engagingly youthful and ever curious, hence the use of technology to augment his preparation. It is 20 years now since the schoolboy trumpeter left Chetham’s School in Manchester, trailing clouds of glory. First he went to Birmingham, at Sir Simon Rattle’s invitation, to spend a year with the CBSO. After a year at Cambridge, which he spent largely on the road, fulfilling dates in his developing concert diary, he upped sticks to Berlin to serve as Abbado’s assistant for a further year.

As he forged his career in Germany, lives in Paris, and holds a permanent position in Stockholm with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, British audiences have not seen much of him in the past two decades. Even the Proms, which welcomes all kinds of waifs and strays, seemed out of bounds. Harding had not appeared there for ten years before his return this summer with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and also with the LSO for the memorial concert to Sir Colin Davis, an all-English programme capped by Elgar’s second symphony.

Next month he will be conducting the LSO, of whom he is principal guest conductor, in programmes dominated by Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and the second act of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. And audiences will see a very different conductor from the one anointed by Abbado and Rattle when he was barely out of short pants. If you are the youngest person to conduct at the Proms, and the youngest to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic, as Harding was, you wear a dartboard on your back, and critics were not shy to fling a few arrows his way.

‘Three years ago,’ says Harding, ‘I was at the San Siro in Milan with Daniel Barenboim, watching Inter play Manchester United [Harding is an incorrigible United fan]. He asked me how I thought things were going, and I told him that I was just beginning to get the feel of it. He said that when he started conducting in the Sixties Herbert von Karajan told him that it would take at least ten years before he got to grips with it.’

There have been some wonderful moments along the way. Standing in for Rattle in Paris in December 1995, he met Peter Brook, who invited him to conduct Don Giovanni at the festival in Aix-en Provence, which became a summer home for many years. But there have been troubles, too. A poor run of form, as sportsmen might say, eight years ago coincided with the break-up of his marriage to Béatrice Muthelet, a violist in the Mahler Chamber Orchestra Harding was then leading. At such times, there is no easy hiding place, and Harding, to his credit, sought none. ‘I wish he had told us what was going on,’ a member of the Vienna Philharmonic said after some less than harmonious performances at the Salzburg Festival. ‘This orchestra is good that way, more forgiving than people think.’

Harding, to be blunt, was acquiring a reputation as a young man who knew best. Musicians in Chicago bridled when he spoke back to them, though irony often falls on stony ground in America. Then, in January 2007, he went to Stockholm, and has found working with that orchestra to be a joy. Three years ago, in an initiative that has proved to be most significant, he began to work regularly with Mark Stringer, the American professor of conducting at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, who has brought an eager eye to his physical deportment on the podium.

‘He gets me, for want of a better expression. He has an analytical mind, and offers a dispassionate look at the mechanics of conducting. Like a coach observing a tennis player with his serve or a golfer with his swing he can identify problems. I don’t mean going up to Lewis Hamilton and saying, “You can drive a little faster there, take that corner a little bit tighter.” As I get older I realise just how difficult a business conducting is, and how helpful an outsider’s judgment can be. Now I look back and think, “How on earth did I get away with it for so long?”

‘I was gratified to see film of Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in the Fifties in Japan. He is not yet Karajan. His arms are not in the right place, and yet he was about 50. Look at him ten years later and he has become the master of physical control that everybody remembers, but he wasn’t at that time. I’ve seen a tape of Carlos Kleiber doing Falstaff in Zurich in the Sixties. It’s a fabulous performance but it isn’t the Kleiber he became. These are important lessons for a young conductor to learn’.

Did the young Harding really think he knew best? ‘I did a lot of things when I was young, and I did a lot of things badly, which is quite normal. It has taken a long time to escape from some of the follies. For instance, I recorded Don Giovanni when I was 23 and I am quite proud of it. All my ideas were based on what was in the score. I wasn’t simply trying to impersonate Giulini. But my view may have changed in the intervening years, and it can be difficult to persuade people that that is so. I had wonderful opportunities when I began. I just wish I could have the benefit of them and that nobody else could remember them!

‘To conduct is to do a completely different job from one week to the next, or to confront different working practices. Obviously, going from Stockholm to Berlin to the Mahler Chamber Orchestra brings different challenges. You have to be aware of what works in any given orchestra, and know that you are not going to change them. I was determined as a younger conductor that I had something to say, that I wasn’t going to let the musicians do all the work.’

It is an older, wiser man who enters the summer of his musical life with a full diary. As well as his symphonic work with the grandest European orchestras, he has conducted Wagner and Verdi this year in the opera houses of Milan, Vienna and Berlin, and taken the La Scala company to Japan. He returns to Milan and Berlin before the end of the year, and goes to Boston for the first time. It’s all a long way from that day in February 1993 when, as a 17-year-old pupil at Chetham’s, he sent Rattle a tape of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire he had cobbled together with a group of pals, and received a summons to Birmingham where Rattle told him how he had got it wrong.

‘I was an arrogant 18-year-old when I went to Cambridge, though I think university for many people comes at the wrong time of life. It should be obligatory for everybody between the ages of 30 and 33.’ That doesn’t sound like a chap who knows everything. Rather, one who is content to remain a student. Thirty-eight is no age for a conductor. His journey has only just begun.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Daniel Harding conducts the LSO at the Barbican on 20 and 28 November.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in