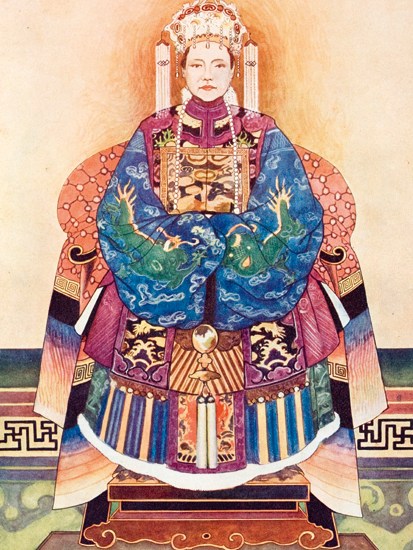

For susceptible Englishmen of a certain inclination — like Sir Edmund Backhouse or George Macdonald Fraser — the Empress Dowager Cixi was the ultimate oriental sex kitten, an insatiable, manipulating dominatrix who brought the decadent Manchu empire to its knees. While all seems lost, as foreign troops burn the Summer Palace in Peking, she is to be found, thinly disguised, in the pages of Flashman and the Dragon, locked in our hero’s rugged embrace. More recently, it has suited communist historians to concur with Flashman that she was ‘a compound of five Deadly Sins — greed, gluttony, lust, pride and anger — with ruthlessness, cruelty and treachery thrown in’.

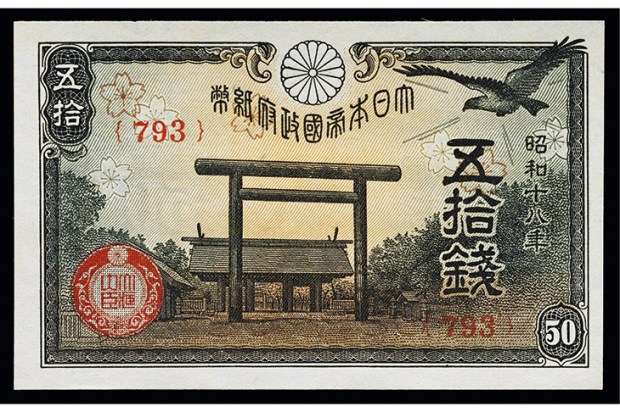

In present-day China her rule is blamed for half a century of foreign bullying, humiliation and decline. Every visitor to the Summer Palace is shown the beautiful lakeside pavilion in the shape of an elegant marble pleasure boat and told how Cixi spent funds destined for the imperial navy on such extravagant fripperies — which ultimately led to Japan’s victory over China in 1895 and the loss of Taiwan.

Between 1860, when an Anglo-French expeditionary force sacked the Summer Palace in the Second Opium War, and her death in 1908, this half-literate, eighth-rank concubine somehow ruled China from behind a screen. She governed first through her only son, the Emperor Tongzhi, and after his early death through two adopted children. In 1911, the last emperor of China, Puyi, abdicated, ushering in the chaotic warlord era and then the dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek.

Our image of Cixi and her court has been heavily influenced by the ardent nationalist Kang Youwei, who fled abroad in 1898 after a failed conspiracy. Kang, having been a close associate of the Emperor Guangxu, claimed he knew all about the debauched goings-on in the Forbidden City. His stories of Cixi’s nightly orgies were subsequently picked up and recycled by China hands such as J.O.P. Bland and Backhouse.

Cixi did execute six of Kang’s associates and imprison the Emperor Guangxu on an island in Zhongnanhai, the current headquarters of China’s leaders. These men are now officially regarded as heroic martyrs, prevented by the Empress Dowager from pushing through the first comprehensive package of modernising reforms. And Cixi’s subsequent support of the fanatical Boxers, who besieged the Foreign Legations in 1900 and massacred diplomats and Christians, has lent further credibility to the lurid tales about her. It was certainly a mysterious episode. The Boxers could have destroyed the Legations’ defences at a stroke had they used the artillery available. And why, in the middle of the mayhem, did Cixi send the starving defenders baskets of fruit and vegetables?

Jung Chang, who has previously set out to demolish the reputation of Mao Zedong, now attempts to rescue the last empress’s reputation by sifting through the newly available internal archives of the Manchu court and unpicking the truth behind the titillating fantasies. And the story she delivers is a fascinating one.

Somewhat disappointingly, it turns out that Cixi was never China’s orgy queen. For a start, her most beloved companions were eunuchs. She did drink only breast milk, and smoke two pipes every morning — and she even enjoyed a foot-rub. But her court, far from being luxurious, was permanently strapped for cash, depending heavily on customs revenues gathered by a diligent Ulsterman, Robert Hart. He emerges as a major player, a trusted counsellor to Cixi in her many crises. One of the oddest elements of the story is that, apart from Hart, all the men at court — Cixi’s husband, son, uncles and nephews — seem weak, hysterical and pusillanimous. Cixi herself emerges as a sort of Margaret Thatcher figure, the only person with any dynamism.

On the death of her husband, the young Cixi manages to seize power in a palace coup, because the aged council of regents, too hidebound to modernise, completely underestimates her. As time goes by, those manoeuvring around her continue to make the same mistake, and she repeatedly takes charge. Indeed, the only time her robust commonsense deserts her seems to have been during the Boxer uprising. But she later compensates for this by successfully restoring relations with the foreign powers and radically changing Chinese society for the better.

For anyone who has been baffled by the accepted history of the late Qing dynasty, this book is wonderfully illuminating. Through the story of Cixi, Jung Chang explains how the Manchus, weakened by internal rebellion, threatened by predatory western powers and outpaced by the rapid modernisation of Japan, managed to hang on to their empire for so long. By rights, they should have gone the way of the Aztecs or the Ottomans.

Thanks to the Dowager Empress, medieval China was finally brought into the modern age with the introduction of railways, electricity, telephones, a modern-style navy and military, and a changed education system. But, unlike Mao, Cixi was no despot, executing only a few dozen political enemies, mostly plotters, over the course of four decades in power.

Jung Chang certainly gives Cixi her due, but I wonder if this version of the ‘Old Buddha’, as she liked to call herself, will be accepted in China. There are no women in the top echelons of the party today, and those in the past who have desired or wielded power — from the Tang dynasty’s Empress Wu Zetian to Jiang Qing, Mao’s would-be successor — have invariably been presented as mad, hyper-sexed minxes. I fear the Backhouse version of history may be set to stay.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in