It’s a cynical start to the Royal Opera’s season to have this 1984 production of Puccini’s last opera Turandot. Not that a new production would improve things, whatever it was like. Turandot is an irredeemable work, a terrible end to a career that had included three indisputable masterpieces and three less evident ones, counting Il Trittico as one. Any operatic composer who gets to the stage, as Puccini had, of searching through one play or novel after another, dissatisfied with any subject he is offered, should almost certainly give up. The greatest and most successful either produce operas like cows produce milk, Handel and Donizetti being obvious examples, or have them wrested from them by the sheer impact of their experiences and the imperative need to give them artistic form, Wagner being the clearest case.

Puccini’s agony was that he had become, and knew it, more sophisticated and canny a composer the longer he carried on, but he had already created works in which his favourite subjects, tormented and suffering women, and the various kinds of men who caused their suffering or who suffered because they did, were exhausted. So his masterpiece Butterfly was eventually followed by the medium-high camp of The Girl of the Golden West, then there is the moderately charming operetta La rondine, and the Trittico, which has lots to be said for it, but doesn’t reach the height of the Big Three. Turandot had some of the right constituents for him: hopeless and ignored love, frigidity, torture and an exotic setting, enabling him to employ unusual instruments. But fatally it has a happy ending, which Puccini couldn’t really believe in, and his own death prevented him from working it out as painstakingly as he had the rest of the piece — not that it could have saved an opera that is already disgusting.

The character who has most to sing is, unusually, the tenor hero, Calaf. At Covent Garden the role is taken by Marco Berti, a stentorian tenor in the del Monaco tradition, and one who stands and delivers without acting or expression. There isn’t a lot you can do with Calaf, who has never noticed that Liù is in love with him, and who stands by as she is tortured by Turandot’s henchmen in order to reveal his name, when all he needs to do is to tell her and take whatever consequences there may be. And once Liù has killed herself because she can’t stand any more pain, Calaf forgets about her, and about his frail old father Timur who just disappears, and turns all his attention on Turandot. Not that he loves her, although she climaxes by telling him his name is Amor. Given the extremely brief and unpleasant relationship between them up to that point, love can only mean lust, as it usually does for Puccini’s men, but not for his women.

If we judge by the music, Puccini was more inspired, and predictably, by Liù than he was by the two central characters. Her two arias, which are sung in this production by the winningly diminutive Eri Nakamura, take him on to home ground, but that isn’t where he wants to be, so she is really an irrelevance. True, Turandot asks her how she can bear to be tortured, and Liù explains that it is because she loves Calaf, but that only leads Turandot to command the guards ‘Tear the secret from her!’ so when Turandot finally admits to loving Calaf, Julian Budden is right in saying that this is ‘hormonal, a case of nature reasserting itself after years of repression’. And he goes on to say, ‘Only a miracle of musical transcendence could redeem the two principals; and that is something that lay outside Puccini’s range.’ Yet he concludes, ‘Turandot remains unique and unrivalled,’ which in a sense is true, but not as Budden means it. But every Puccini authority raves about its bitonality, the influence of the most avant-garde composers on it, and so forth, as if the surprising harmonies and orchestration could justify this artful rubbish. And for all its dissonances and adventurous sounds, after a few bars anyone would recognise its composer, it’s just that he’s put on a different suit.

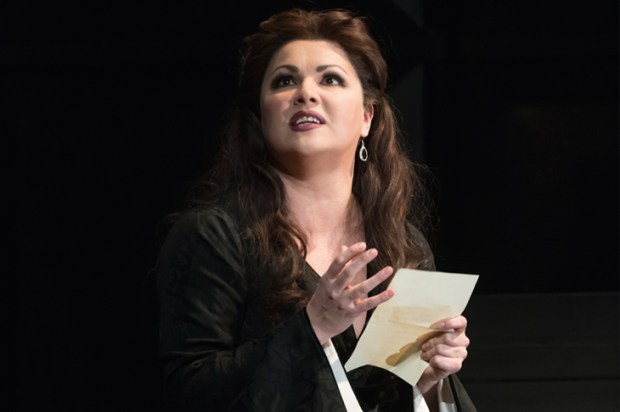

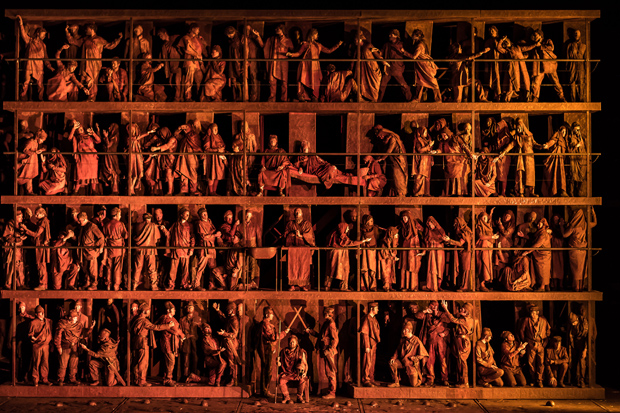

Turandot is played by the American Lise Lindstrom, making her Royal Opera début. She looks good, she sounds implacable, she sings the role worldwide, and one hopes her voice survives that and is soon put to more worthy purposes. The production, a full-scale dance-and-song affair, certainly has plenty to keep the eye busy, only emphasising by its unique sumptuousness the void that lies behind.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in