The popular conception of Dame Laura Knight is of an energetic woman piling on the paint in the back of a huge and antiquated Rolls-Royce at Epsom Derby, the door propped open to the view, or charging off in pursuit of gypsies, clowns or ballerinas. A widely popular and successful artist, she painted people in action in a robust, realistic style, and was able to compete with men on their own terms, managing to get herself elected to that hitherto almost entirely masculine preserve, the Royal Academy. But wasn’t there something slightly mannish about her? Her pal Alf Munnings made a joke about that, and certainly you see her kissing her model Ruby on the lips in the fascinating news clip about her famous war painting ‘Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech- Ring’, which shows Laura and the chaps all smoking like troopers in the Academy galleries. (Those were the days!) She was married to the mild-mannered Harold Knight, a painter whose work hasn’t lasted as well as hers, and they had no children. Any suspicion that she might have been lesbian is offset by her evident adoration of Squire Munnings. But was that admiration for his great skills as a painter, or for his unusual personality?

Enough of these biographical speculations, it is the art that counted most for these painters — or was it? Surely it was not for nothing that both wrote extensive autobiographies (Laura two volumes, Sir Alfred three), and recognised the value of presenting a nicely honed self-image to the public to enhance their saleability as artists. Munnings was the bluff countryman, the no-nonsense opponent of Picasso, while Knight was the down-to-earth working woman who let it be known that she preferred to take a bus home rather than a taxi after dining with the Prince of Wales. To a degree this was calculated showmanship: they each exaggerated aspects of their personalities, just as actors traditionally did (wearing flamboyant clothes and stage make-up in ordinary life): it was good for business. To balance the myth of the genius starving in the attic, there have always been artists skilled in the ways of the world. Laura Knight was one of these.

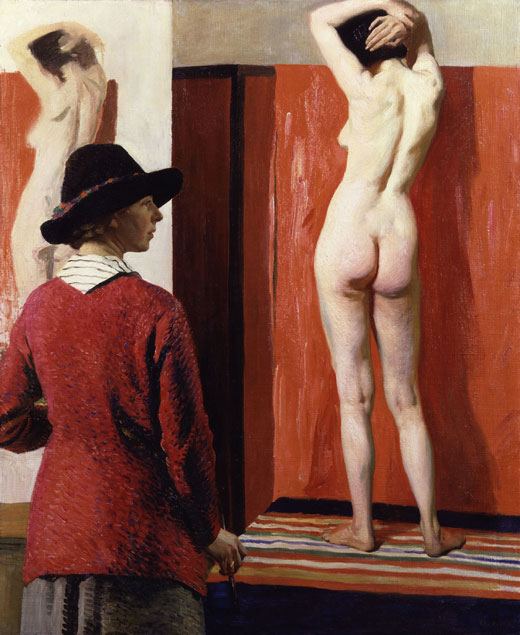

Unlike today’s devoted self-promoters, who have demonstrably less artistic originality than business acumen, Laura Knight (1877–1970) was a real painter of considerable talent and unimpeachable industry. She is best known for her figures in landscapes, so this smallish exhibition of portraits presents a less familiar aspect of her output, though with many of her strengths to the fore. The exhibition starts with her marvellous ‘Self-Portrait’ of 1913, in which she depicts herself in an old red cardigan in the studio between two nudes, one the model, the other her painting of the model. This then is a picture within a picture, a slightly tricksy image of her painting herself, but also a wonderfully direct portrayal of nude and clothed flesh, daring in conception and dashing in its paint. We the viewers are made to feel very much the observers (or voyeurs) — a role often assumed by the artist and viewer together — presented as we are with three back views (the model, Laura’s painting of her, Laura herself), though the artist has turned her head to allow us to admire her strongly featured profile. There is a further relevance to this image. As a female art student, Laura was denied access to nude models, which she felt gave the male students an unfair advantage. Here she is setting the record straight, and showing us all that she can paint a nude with the best of them — and actually produce something more lively and interesting than most.

With this early self-depiction is ‘Rose and Gold’, a portrait of the professional artist’s model Dolly Henry, a familiar figure to anyone who has seen the new Munnings film Summer in February. Tragically Dolly was murdered in 1914 by her lover, the talented but unstable painter John Currie, who subsequently killed himself. There is a prophetic madness to Knight’s painting of Dolly, the colour horribly overheated, the floral backdrop encroaching on the girl, her human identity threatened by an excess of pattern. The powerful but informal open-air group portrait of fellow artist Lamorna Birch and his daughters has a similarly vivid painterly patterning, but the design is held in check and makes more expected sense. The nearby ‘Ballet Girl and Dressmaker’ (1930) is cracking badly – the paint break-up being particularly noticeable on her arms — and the sensitive watercolour, gouache and charcoal study for it makes more of an appeal. I remember this drawing with affection in Nottingham Castle Museum when I was an art history student in the 1970s and Knight, who hailed from Nottingham and was not long dead, was still a local presence.

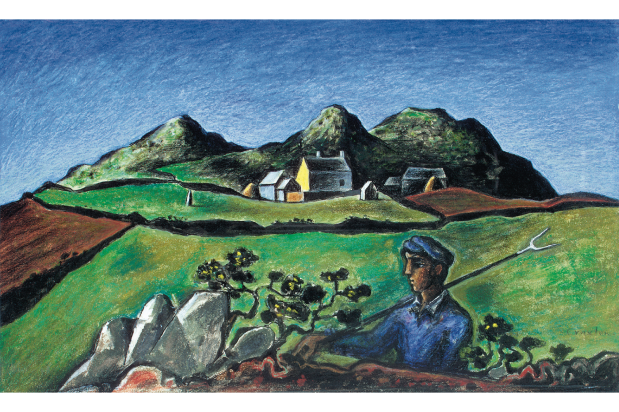

Laura Knight was made a Dame in 1929 and for much of her adult life was a household name. She grew up in Nottingham where the family home was dominated by strong women, and her mother gave art classes to support her children. Laura showed early talent, attending Nottingham Art School from the tender age of 13. There she encountered Harold Knight, the star pupil on whom she modelled herself, setting out her easel behind his to emulate his every move. They married in 1903, honeymooned in London (visiting the National Gallery every day) and spent time in Holland, joining the artists’ colony at Laren before moving to Cornwall in 1907 and joining the Newlyn-based painters Lamorna Birch, Ernest and Dod Procter and Alfred Munnings. The Knights stayed in Cornwall until 1919 when London became their base, and from then on Laura became increasingly famous and celebrated — a public figure indeed.

Besides handling oil paint with dexterous assurance, Knight was good with watercolour: witness her group of drawings of black patients in the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, ‘Chloe’ and ‘Pearl Johnson’ especially. In these direct observational studies there is no trace of the sentimentality that sometimes overtakes her pictures, particularly when attempting the exotic. The room of clowns and gypsies hovers on the edge of mawkishness, and although the characterisation is strong and the paint typically vivid, the presiding emotion is often too indulgent for such self-consciously outsider figures.

A room of Knight’s famous war paintings, full of bravura detailing, gives way to a final room of portraits of the great and the not-so-great. A young Paul Scofield is here and a rather beautifully modelled 1929 oil entitled ‘Susie and the Wash Basin’, of a Cornish fisherman’s daughter. If you can’t make it to London, the exhibition travels to the Laing, Newcastle (2 November 2013–16 February 2014), and then to Plymouth Art Gallery (1 March–10 May 2014). The country is certainly reawakening to the glories of Dame Laura.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in