‘I don’t really like most of the music you play,’ said the tall blonde woman with whom I share my life. ‘There are no tunes. Where are the tunes? A lot of it sounds like the sort of thing you’d hear in Topshop.’

I was outraged. Admittedly, the song playing at that moment — a droll little thing called ‘Boring’ by The Pierces — didn’t exactly boast a killer melody, but even so. Like any music obsessive worth his salt, I pride myself on my ability to spot a decent tune from 40 paces, even if many of them are couched within the acoustic, minor-key, vaguely melancholy textures I tend to favour. ‘It all sounds the same,’ said the tall blonde woman, warming to her theme, as the excellent ‘Boring’ was replaced by the next track on the album, which was just boring, unfortunately. Hell isn’t other people, I told her. Hell is other people’s taste in music.

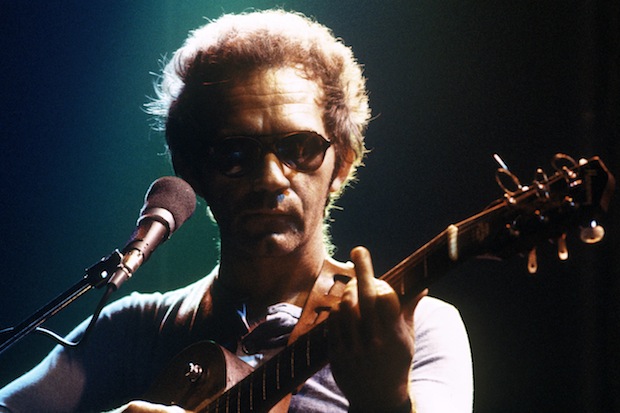

I must be fair: she has reason to feel provoked. Since J.J. Cale breathed his last a couple of weeks ago, I have been playing his music to distraction. I own nine of his albums, and to the non-aficionado, they all sound pretty similar. To the aficionado, too, they all sound pretty similar, because they are all pretty similar. Having acquired six (say), I never quite figured out why I needed a seventh, but buying music has never been an entirely rational activity, and is even less so now that we tend to do it late at night on Amazon after a few glasses of something agreeable. Cale was unusual in that when he recorded his first album in 1972 he was already 34, so he essentially arrived fully formed. That album, Naturally, set the template, and his many later albums refined it, but not by much, if we are to be honest. Critical consensus has it that the early albums are the best, but while there was a definite dip in quality during the 1980s, Guitar Man (1996) is pretty solid and 2004’s To Tulsa and Back has some of his very finest songs. Just to make absolutely sure, I have been playing most of these albums quite a lot of the time.

Cale was an original. As Eric Clapton has said, his songs are not quite blues, not quite folk, not quite country, but somewhere previously uncharted in between all three. The actual song structures are very simple, and the lyrics are almost artlessly straightforward, conning you into the impression that you’re sitting on a porch somewhere, listening to some old geezer strumming his guitar. Cale rarely breaks sweat. He is less likely to ‘rock out’ during a song than doze off. A few years ago, on his Radio 2 blues show, Paul Jones played a track from Cale’s excellent 2006 collaboration with Clapton, The Road to Escondido. ‘Mellow,’ said Jones afterwards, as though someone had just spat in his tea. But to make music sound this easy is hard work.

Although many of Cale’s songs refer in the lyrics to his idleness, most of the albums were self-recorded and involved Cale painstakingly layering instruments on top of each other, more in the manner of modern dance music than the dreary blues workouts Paul Jones so reveres. Every song starts with the groove. Texture comes about through experimentation and, on the later albums, the enthusiastic embrace of technology. So the songs he wrote may have been simple, but the records he made were anything but.

Cale had a vision, then, and pursued it unstintingly for 40 years. He was helped in this by the equally unstinting support of Clapton, whose cover of ‘After Midnight’ in 1970 enabled Cale to get his first major record deal. Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Band, Captain Beefheart and many others also covered his songs, but rare is the Eric Clapton album without a Cale song on it. He was also a significant early influence on Mark Knopfler: ‘Sultans of Swing’ sounds more like J.J. Cale than Cale himself. He was once asked whether it bothered him that fellow musicians revered him while many punters didn’t even know his name. ‘No, it doesn’t bother me,’ said Cale. ‘What’s really nice is when you get a cheque in the mail.’

Ferociously strong melodies, though, were never his strong point, which is one thing his songs have in common with the stuff you’ll hear in Topshop. Oh, to hear ‘Cocaine’ or ‘Low Down Dirty Shame’ or ‘Blues for Mama’ there, and watch the shoppers run screaming for the door.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in