Australia is not yet in full blown decline. Not yet. But the architecture of decline has been assembled with such patience, and such denial, that many Australians have not fully registered what is happening.

The frog settles into the pot. The temperature rises gradually, a few dollars more at the checkout, a heavier mortgage repayment, one more month in which wages do not quite stretch, another eye-watering energy bill. The frog adjusts. The water warms. Bills accumulate, the overdraft deepens. Still the frog remains, accustomed now to the heat. The water begins to simmer. And by the time the frog realises the danger, its muscles have already weakened. The water boils.

The data deserves to be stated plainly. Real per capita GDP fell for seven consecutive quarters across 2023 and 2024. Real household disposable income declined by eight per cent in the two years to March 2024, the largest fall of any OECD nation during a period in which the OECD average rose by 2.6 per cent. Australians are not imagining the squeeze. They are living it.

The fiscal picture is equally stark. Gross Commonwealth debt is about to cross one trillion dollars. Government spending as a share of GDP, outside wartime and pandemic conditions, has reached record levels. Public demand now accounts for roughly 29 per cent of nominal GDP, against a long-run average closer to 24 per cent. This is not a temporary aberration but a structural expansion of the state.

The NDIS, conceived with genuine compassion, has become a fiscal leviathan, expanding at multiples of the broader economy and exceeding every projection made for it. Yet even it is not the fastest growing line item in the federal budget. That distinction now belongs to interest payments on Commonwealth debt. We are borrowing not to build, but to service yesterday’s indulgences.

Inflation has come down from the seven-per-cent peak reached after governments decided that paying people not to work was costless. But moderation is not reversal. When the rate of increase slows, the cumulative price level does not unwind. Goods and services that cost 30 per cent more than they did four years ago remain 30 per cent more expensive even if prices stabilise. Families do not experience inflation as an abstract rate. They experience it as a permanent ratchet.

The causes are not mysterious. An energy policy driven more by ideology than engineering has imposed internationally extraordinary costs on households and businesses. A migration intake that has outstripped housing and infrastructure capacity has intensified pressure on rents, services, and social cohesion. A regulatory environment that suppresses private investment has ensured that the private sector, the only durable source of the wealth that funds everything else, has underperformed precisely when it is most needed.

The result is a government that, having constrained the conditions for growth, now finds itself with only one lever remaining. Unable to expand the pie, it redistributes the existing slices while ensuring its own constituencies are protected first: the public sector, the administrative apparatus, the Canberra lanyard class orbiting both.

This combination of elevated spending, mounting debt, rising interest costs, suppressed private investment, subsidies for the well-connected, and ideological resistance to reform has a precedent, one policymakers once studied carefully in order to avoid repeating it.

Argentina was once among the wealthiest nations on earth: prosperous, resource rich, confident. The governing philosophy that subordinated economic reality to political preference acquired a name there: Peronism. Treasurer Jim Chalmers calls his approach values based capitalism. Australia is not Argentina. But decline does not begin with hyperinflation and riots. It begins with excuses.

Meanwhile, the Liberal party confronts its own reckoning.

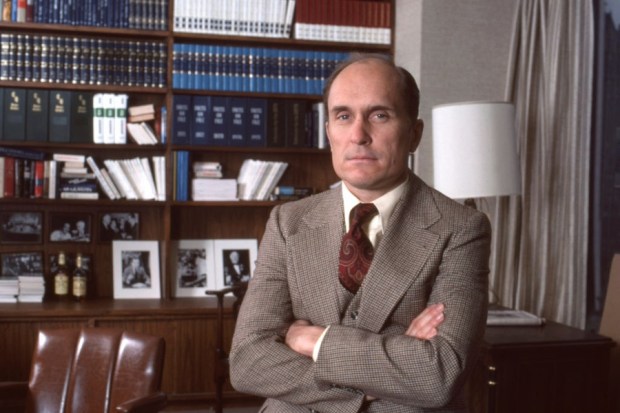

As newly elected opposition leader, Angus Taylor has inherited a party that, by his own admission, may not survive another electoral defeat. He does not simply need to win government. He must reconstruct a party capable of governing, one that can generate ideas, sustain conviction and offer something more substantial than the reactive populism that has sustained the Liberals for much of the past decade.

The task is Augean. But unlike Hercules, Taylor cannot divert a river. He must reform an institution, populated by many of the same people who presided over its decline.

A personnel reckoning is overdue. Parliament’s corridors are filled with a professional political class who discovered that a taxpayer-funded salary, secure superannuation and generous perquisites provide powerful incentives to avoid positions that might jeopardise tenure. The staffers turned MPs. The factional operatives turned ministers. The middle-aged student politicians.

They are not villains. They are rational actors responding to incentives, people who have learned that survival rewards caution, punishes boldness, and requires keeping out of the game those with greater ability but less appetite for treachery.

Another requirement is intellectual. For too long, the Liberal party has outsourced its thinking to focus groups and polling firms, producing a movement that stands for whatever it believes the median voter in a marginal seat wants at any given moment. That is not leadership. It is retail politics masquerading as principle.

As Steve Jobs once observed, ‘People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.’ Leadership requires argument. It requires persuasion. It requires, occasionally, telling voters things they may not yet wish to hear. A party of government cannot simply ask the electorate what it wants and promise to deliver it back gift-wrapped. That is not leadership. That is customer service.

What Australia requires is not conceptually complex, though it is politically demanding. Reform that restores the conditions for private investment; a meaningful retreat of the state; energy policy grounded in engineering and cost; fiscal restraint that shields future generations from debts they did not incur; and an honest conversation about what sustained prosperity entails. Such a conversation asks something of citizens rather than merely promising them something.

Which is why the health of the opposition is not merely a partisan concern. Even those indifferent to the Liberals’ fortunes should recognise that a credible alternative is the minimum condition of democratic accountability. Without one, there is little to restrain what is shaping up to be the worst government in half a century, an administration that has presided over the sharpest deterioration in Australian living standards in decades and shows scant sign of recalibrating.

Australia stands at a crossroads that nations encounter only occasionally. One path leads to recovery: the slow, unglamorous work of reform, discipline, and renewal. The other continues the present trajectory: redistribution amid stagnation, rising debt, institutional drift and social discord.

The hour is late. The margin for error is narrow. And the cost of pretending otherwise compounds with each passing year.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Dimitri Burshtein is a Senior Director at Eminence Advisory. Peter Swan AO is professor of finance at the UNSW-Sydney Business School.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.