Recent weeks have seen a political and military earthquake in Syria. Nearly 14 months after driving Bashar al Assad from Damascus, President Ahmad al Sharaa is on the point of extending his transitional government’s complete control over the third of Syria east of the Euphrates. For all practical purposes, this will mean the end of the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces, the SDF, which had been the West’s allies against Is is. Time is being called on the semi-independent and self-declared autonomous Kurdish province of Rojava which has been created by the SDF during Syria’s civil war.

In a swift campaign lasting only a few days, the Syrian army unexpectedly swept the SDF out of the Euphrates valley and appears to have isolated it in its Kurdish-majority strongholds such as Kobane. The SDF lost 80 per cent of its territory in three days and no longer occupies a contiguous area of land but only an archipelago of pockets predominantly inhabited by Kurds. The only question is this: will the end of the SDF and Rojava be by agreement, or will it be bloody? There is enough antagonism verging on hatred on both sides to make the latter a very frightening possibility.

What the SDF wanted was a largely autonomous Kurdish province in a federal Syria in which the central authority was weak. In Damascus, President al Sharaa insisted on a united Syria with a strong government that can bring peace to the country and rebuild it. Despite there being many unresolved tensions, most Syrians probably agree with Sharaa. Balkanisation of Syria would risk following a path like that of post-Gaddafi Libya – or, worse still, of Iraq after the toppling of Saddam Hussein.

After nearly a year of attempts at negotiation with the SDF, Sharaa felt he was being stonewalled. Besides, the SDF did not have clean hands. By preventing Syrian government access to areas east of the Euphrates, the SDF was depriving it of control over Syria’s borders. The SDF also occupied the Euphrates valley governorates of Raqqa and Deir al Zour with their agricultural and hydrocarbon resources, important dams and precious water. Its intention in doing this was to put pressure on Damascus, even though the people of these overwhelmingly Arab areas did not want the SDF there and actively detested its fighters. It was partly the defection of local Arab tribal militias that enabled the Syrian government to take these areas so swiftly. When retreating, the SDF blew up bridges over the Euphrates and planted mines to delay the Syrian advance.

There is a separatist core in the SDF that effectively wants a Kurdish statelet on Syrian soil and is willing to fight for it. However, Syria and the Kurds go back a long way and the SDF has no right to speak for them all. Saladin, who died in Damascus in 1193, was famously a Kurd. The Crusader castle Krac des Chevaliers was built from 1142 onwards on the site of a fortress with a Kurdish garrison. The Kurds are a proud and hardy mountain people with their own language and culture. Throughout history they have provided soldiers for many armies. They are also notorious for their disunity. Think the Highland clans in, say, the eighteenth century. They are the predominant ethnic group living in a mountainous region which spreads across a vast area of eastern Turkey, northern Iraq and western Iran.

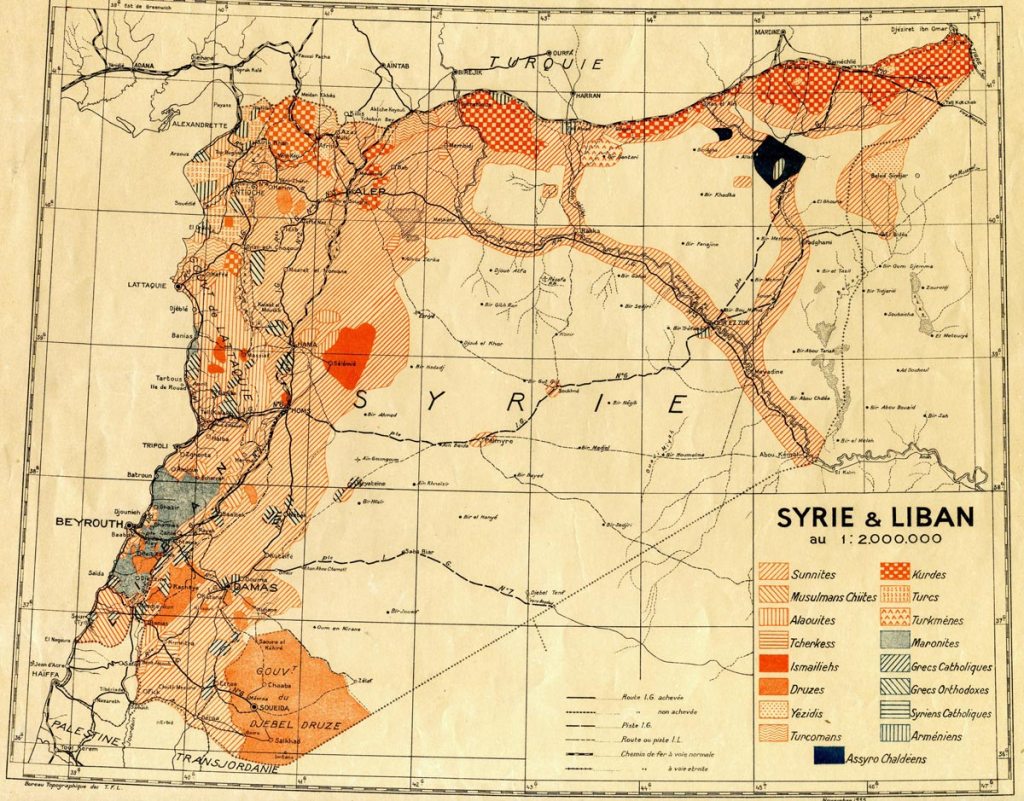

Yet in Syria, where they may be 10 per cent of the population, Kurdish majority areas are not contiguous. Damascus has a large Kurdish suburb, Ruknaddin, dating back to Saladin although today many Kurds there only speak Arabic. But most Syrian Kurds today are descendants of refugees from Turkey who fled to the north and east of Syria after rebelling against Ataturk’s Turkish nationalist government about a century ago. They left their mountains and settled in the steppes around the Euphrates valley where they competed with Arab tribes for pasturage and only became the majority population at a very local level, as the French map from 1935 below shows. There is no area that could be called ‘Syrian Kurdistan’, and Rojava, the area that emerged under SDF control during the Syrian civil war, included many ethnic Arabs as well as others such as Syriac Christians and Armenians.

1935 map prepared by Bureau Topographique des Troupes Françaises du Levant.

1935 map prepared by Bureau Topographique des Troupes Françaises du Levant.

Under the extreme Arab nationalism of the Assad family’s Ba’ath party, the Kurdish language was suppressed and excuses found to deprive many Kurds of their Syrian citizenship. Ethnic Arabs were deliberately settled in Kurdish majority areas. Sharaa has promised an end to all of this. Last year he permitted the celebration of Nowruz, the Kurdish (and Iranian) New Year which was marked in Damascus in 2025. He has also allowed the Kurdish flag to fly in Government-held areas. Now he has decreed that Nowruz will be a public holiday and that the Kurdish language will be taught in Kurdish areas and have an official status. Some SDF units may also be incorporated into the Syrian army.

Some SDF units may be incorporated into the Syrian army

There could be a win-win situation for all, but it means the end of the dream of Rojava. Responsibility for the breakdown in negotiations that led to the fighting is vigorously contested and there is a deep lack of trust. Kurds accuse the transitional government of allowing hate speech in the media, and SDF supporters paint Sharaa as an unreconstructed jihadi. They point to the atrocities that occurred in Alawi areas last March and the Druze heartland of Suwayda in the summer. Yet according to Charles Lister, the director of the Syria Initiative at the Middle East Centre (MEI) in Washington, since then Sharaa and his Ministry of the Interior have encouraged local participation in governance across the country. This has been transformative in the area around Lattakia, where the attacks on Alawis took place, and turned it into one of the calmest areas in Syria. This, Lister points out, could provide a precedent for north-east Syria. It depends, however, on the central government and the SDF reaching agreement if bloodshed is to be avoided.

Can the Kurds trust Sharaa despite his jihadi background? We will see, but we might note that Islamism contains a democratic strain that can be traced back to Jamal al-Din Afghani in the late nineteenth century. There is reason to hope that Sharaa, in his new incarnation as president of Syria, now embodies this tradition rather than being ‘a jihadi in a suit’.