Although the strongest hate speech laws ever passed by the Australian Parliament are now securely ensconced in our statute books, they have already been the subject of some intense scrutiny.

The Combating Antisemitism, Hate and Extremism (Criminal and Migration Laws) Act 2026 has been criticised for its untimely passage, which prevented detailed scrutiny by Parliament and restricted opportunities for public discussion. The law has been criticised for making the crime of hate speech retrospective, for defining the crime by reference to federal and incompatible state laws, and for not providing procedural justice for proscribed groups.

According to the law, a hate crime is conduct ‘that involves publicly inciting hatred of another person … or a group of persons’ because of their race, national or ethnic origin and that ‘would, in all the circumstances, cause a reasonable person who is the target, or a member of the target group, to be intimidated, to fear harassment or violence, or to fear for their safety’.

Thus, the law applies when an individual from the target group feels threatened, is afraid of harassment or violence, or fears for their safety.

This is an entirely subjective test.

Even if there is no intention on the part of a speaker to intimidate, it could activate the draconian legislation, leading to 15 years in jail. The legislation does not deal with radical Islam, and it is ironic that it may, at least potentially, be relied upon by Islamic extremists to combat any criticism of their behaviour.

The main problem with this type of legislation is that the more a group might deserve to be criticised, the more protection it receives from such legislation. Of course, we also know very well that intolerant people tend to feel more easily offended. In this way, the more radical or extreme the person is, the more opportunities he or she will have to use the legislation as an instrument of persecution against those who dare to disagree.

Now, even a constructive comment about a certain religion can be treated as offensive and thus criminalised, because the point of view of the intolerant religionist who feels somehow ‘intimidated’ by any particular comment is ultimately the one that really matters for the purposes of activating such hate speech legislation.

Although it might not be civil to ‘intimidate’ anyone because of his or her religious convictions, we cannot expect to pass through life without unpleasant words spoken to us. Indeed, in a free society, there will always be people who are so sensitive that almost any negative comment will be interpreted by them as bullying behaviour or intimidation. In outlawing robust discussion, the Australian Parliament has opted for Australia to become a less resilient society.

The new law will certainly muzzle people’s free speech, but it will not solve the problem of hate because it will simply go underground to fester and infect. Legislation of this nature, since it aims at what people say publicly, cannot eradicate the thoughts that underlie that speech. As such, this kind of legislation may have the opposite result as that envisaged because it only deals with its public expression without considering the underlying causes.

More importantly, the legislation is a threat to democratic decision making because it could be used even for the purpose of banning political parties that threaten the established ruling progressive parties.

Indeed, if it can be proven that ‘right-wing’ parties promote ‘hate speech’, Australia’s new hate speech laws could potentially produce this outcome. Under the new legislation, these parties could be banned on the ground that they are involved in some form of intimidatory behaviour by criticising mass immigration or agitating against an expansion of First Nations’ rights and privileges or even arguing in favour of retaining Australia Day on January 26.

By way of example, we believe it is not preposterous to suggest that, if One Nation continues to surge in the polls, it could be investigated under the law and become a proscribed organisation.

At this point, we can hear you asking whether our views are disparaging examples of scaremongering and, therefore, not quite believable. To address this concern, we might refer to developments in other countries, for example the United Kingdom and Germany, that have used a comparable law to either proscribe ‘right-wing’ parties or to ostracise them.

In Germany, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution classified the Alternative für Deutschland Party (AfD) as a right-wing extremist organisation. It only suspended its classification on May 8, 2025, in response to AfD’s initiation of judicial steps to have the classification overturned.

AfD won 20.8 per cent of the popular vote in the federal parliamentary election held on 23 February 2025; it holds 152 out of 630 Bundestag seats. The intelligence agency’s designation of AfD as a right-wing extremist organisation would intensify, and justify, increased government surveillance of its activities.

However, according to Article 21(2) of the Basic Law, only the Federal Constitutional Court can decide whether to ban a political party. This Article says that parties whose goals or members’ actions threaten the free democratic order are considered unconstitutional. While the AfD has not been proscribed at this time, the attempt to ban it highlights the fragile state of democracy, defined as a political system that respects the will of the people, in Europe.

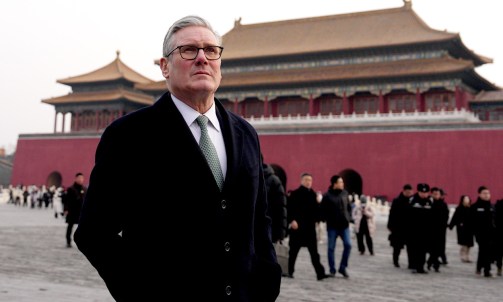

In the United Kingdom, hate speech legislation has effectively abolished free speech. It is common for ten or more police officers to arrive at the homes of law-abiding citizens who have made comments on social media that might be seen as a threat to social cohesion and arrest them. It is in this country that citizens can be arrested for merely displaying a poster inviting people to talk to them about Jesus. More recently, the London Metropolitan Police have banned a Christian ‘Walk with Jesus’ march that was scheduled for January 31 in Whitechapel, citing fears of provoking the local Muslim community and potential violence, although Muslims are allowed to do this.

The statistics in the United Kingdom reveal that, on average, 30 arrests are made per day, or close to 12,000 per year, for alleged offences committed on social media and other online platforms. There are even cases where individuals are found guilty by a court and sent to prison for posting messages online that may be offensive, but certainly not illegal. Ominously, there have been governmental statements to the effect that the UK Reform Party promotes hate and that something should be done about it. Banning, perhaps?

We may well lament these developments, but they are the inevitable result of a process that, in countries like Australia, started in the 1970s when the first discrimination laws were adopted. Laws of this kind are inherently expansionist and invite demands by lobby groups to add new categories of ‘protected’ groups and make them stronger each time something happens that could have been avoided by more stringent laws. While each extension seemed reasonable, even desirable at the time of their adoption, the aggregate we end up with is not what people want and it is not in the public interest.

In this context, the interesting point, often overlooked, is that these laws purport to remedy problems which themselves have been created by successive governments, through lax immigration policies, ineffective law enforcement, profligacy, and poor economic management. If so, these laws effectively blame others for the government’s own mistakes. Subject to the validity of this point, this might also offer the raison d’être for the possible banning of ‘far-right’ parties because authoritarian oligarchical governments are afraid of the well-founded criticisms formulated by these alternative parties.

If that were to happen in this country, especially to One Nation, at least one quarter of Australian electors would be disenfranchised. They would not be able to park their vote with the party of their choice, thereby making a mockery of democracy. Once we arrive at that stage, civil disobedience would become necessary. However, exploring this subject is better suited for a separate discussion.

Naturally, the right of people living in a true democracy to speak publicly about their innermost convictions implies that the adherents of other convictions must be equally free to present their arguments in an equally public manner. This is the basic reality of living in an authentic democracy – a point made by Salman Rushdie, the British novelist who was put under an Islamic sentence of death because he had insulted Muslim sensibilities:

The idea that any kind of free society can be constructed in which people will never be offended or insulted is absurd. So too is the notion that people should have the right to call on the law to defend them against being offended or insulted. A fundamental decision needs to be made: Do we want to live in a free society or not? Democracy is not a tea party where people sit around making polite conversation. In democracies, people get extremely upset with each other. They argue vehemently against each other’s positions.

Rushdie goes on to conclude:

People have the fundamental right to take an argument to the point where somebody is offended by what they say. It’s no trick to support the free speech of somebody you agree with or to whose opinion you are indifferent. The defence of free speech begins at the point where people say something you can’t stand. If you can’t defend their right to say it, then you don’t believe in free speech. You only believe in free speech as long as it doesn’t get up your nose.

In a true democracy, the legal system would never create a ‘right’ for people not to feel offended or intimidated. And yet, the new law passed by the Australian Parliament is specifically designed to promote this sort of anti-free speech intolerance that penalises any disapproval of a person’s beliefs. Given the ongoing atmosphere of fear and intimidation that this sort of legislation creates, from now on, it will not be uncommon to find many Australians afraid of voicing any criticism of controversial religious beliefs.

Naturally, it is understandable that we might prefer people to moderate their claims and avoid comments that might cause unnecessary offence. But a requirement that citizens have their speech controlled by the government in the name of tolerance is an unacceptable abrogation of their right to free speech. Indeed, in a normal democracy nobody should expect to be completely exempt from having to face strong criticism of their values and beliefs. As the European Court of Human Rights once observed,

Those who choose to exercise the freedom to manifest their religion, irrespective of whether they do so as members of a religious majority or a minority, cannot reasonably expect to be exempt from all criticism. They must tolerate and accept the denial by others of their religious beliefs and even the propagation by others by doctrines hostile to their faith.

Democracy involves the right of citizens to freely express their opinions without any fear or threat of punishment. As properly understood, democracy presupposes an open exchange of ideas that requires unqualified freedom of speech. Although a citizen’s opinion may not be the most politically correct, he or she must still have the democratic right to express their views without the risk of criminal punishment, even if these views are found to be wrong.

In conclusion: any society that allows the government to create legislation that clamps down on the citizen’s basic right to free speech has objectively started moving from authentic democracy to a more disguised form of an elective dictatorship. Accordingly, unless we understand the consequences of an expansive interpretation of the new hate speech laws and we develop a better sense of self-respect and dignity, the countries which are the beneficiaries of the great traditions of Western Civilisation, including Australia, may irreversibly become less open societies.