Most things that seemed like a good idea at the time eventually land somewhere between disaster and calamity. In Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company, investigative journalist McGee takes a deep dive into the company’s foray into the Middle Kingdom, with results that are both informative and alarming.

It is easy, these days, to think of Apple as a corporate behemoth with a stable of revolutionary products and an ubiquitous brand. But this was not always the case. In the late-1990s, the company was nearly bankrupt, lacking the funds to back its new range of cell phones and related tech products. The answer, as McGee establishes through a series of interviews, was to lower costs by moving production offshore. China was putting out the welcome mat to Western companies, and the prevailing idea at the time was that more financial integration would lead to democratic reforms.

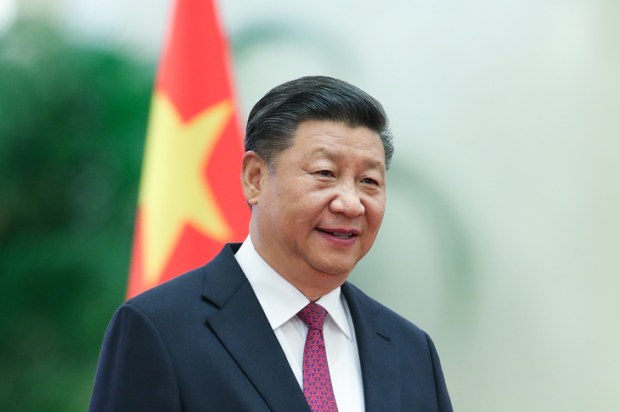

So, in 2003, Apple dived in and before long, massive factories had been built, and vast numbers of Chinese workers were being trained to assemble iPods and iPhones. The bonus was that Apple could access the burgeoning Chinese market, which quickly became a crucial part of its recovery. All this might have worked, except that in 2013, Xi Jinping ascended to the big chair, and he had no doubt about who was really working for whom. The Apple executives accepted him, especially as he cracked down on any sign of labour activism and was a genial host at corporate functions. But in the background, Apple’s proprietary technology was being quietly transferred to Chinese firms, and in a few years, those firms became competitors to Apple, not just in China but in global markets.

The problem for Apple, says McGee, was that it was now committed to China, despite Xi’s creeping authoritarianism. No matter: Apple eventually became the world’s first US$3-trillion publicly traded company, and everyone had an iPhone in their pocket, so it must have found the magic formula.

McGee punctuates the story with some remarkable numbers. By 2015, Apple had invested about US$55 billion in China, and it claimed to have trained over 28 million Chinese workers since 2008. In fact, the scale of Apple’s involvement began to ring alarm bells in Washington, and after Trump’s election, he pushed Apple to bring its operations home. McGee is somewhat sceptical about this, and he points out that Apple’s much-ballyhooed new factory in Texas makes only second-tier products. In an incredible irony, Apple had to fly in Chinese engineers to get the factory running properly.

It is certainly true that Apple has been remarkably successful in leveraging its Chinese connection, but McGee sees the seeds of failure already sprouting. The company seems to have lost its innovative edge and does not seem to know how to deal with nimble, well-funded challengers. Xi is much less accommodating than he used to be and has brought in regulations to curb Apple’s growth. Rock, meet hard place.

McGee tells the story with calm authority, although he sometimes gets bogged down in unnecessary details. The book will probably soon appear on the reading lists of business courses as a case of corporate capture, and as a salutary example of the need to look beyond next year’s profits.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future comes at the question of China from a different angle. Wang, a Canadian technology analyst with ties to several American think tanks, wants to understand how China has moved so far, so quickly, and he identifies a cultural emphasis on engineering as the key. Most of the Politburo heavyweights have engineering backgrounds, and they apply ‘get it done’ thinking to every issue, even social problems. Wang sees America, by contrast, as a society run by lawyers who specialise in blocking opponents rather than building things.

The engineering model can sometimes be spectacularly successful, as seen in the construction of large projects and the development of entire industries in record time. But the approach can also lead to epic failures, such as the construction of empty cities in rural areas. Equally, an engineering approach leads to repression, corruption and a staggering allocation of resources to surveillance and social control. The political class has only a hammer, so it sees every problem as a nail.

Wang has lived in China, and much of the book is based on personal experience and anecdotes about people he encountered, such as during a bike ride from Guiyang to Chongqing in 2021. He has interesting things to say about the high quality of China’s infrastructure and the simmering dissatisfaction with its engineering culture.

One problem with Breakneck is that it is a collection of essays, and the parts occasionally feel disconnected. Nevertheless, Wang obviously has a deep understanding of his subject, and he avoids drawing easy conclusions from the engineer/lawyer paradigm. He believes that both China and the US could learn important lessons from each other if they could get past their competition for the role of the world’s leading power. Possibly, but it does not sound likely.

Taken together, these two books reveal a great deal about how China operates, the arc of its development, and where it is going from here.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.