If Reform get into government, there is one man they seem likely to turn to for guidance. He is an obscure figure, unknown to many, yet has acolytes across the political spectrum – from Dominic Cummings to Gordon Brown. His name is Richard Burdon Haldane and he died almost a century ago.

It was recently reported in this magazine that Danny Kruger had been seen carrying ‘a well-thumbed copy’ of the most recent biography of Haldane. I wrote that book. In it, I describe how Haldane reshaped Britain in the early 20th century – and how, should others choose to follow his example, he might help to transform it again today.

Haldane believed power should move upwards only when it demonstrably improves outcomes

The blue plaque on Haldane’s Westminster home reads: ‘Lord Haldane 1856-1928. Statesman, lawyer and philosopher.’ He entered the great Liberal government of 1905 as Secretary of State for War, was elevated to the Lords in 1911 to steer the Parliament Act through the Upper House and was then driven from office in 1915 by a campaign of hysterical and unfounded accusations in the Conservative press. He spent the following years immersed in administrative reform, philosophy and judicial work at the Privy Council, before returning to office as Lord Chancellor in Labour’s first government in 1924. Haldane had a profound influence on British life. On his death, the Times described him as ‘one of the most powerful, subtle and encyclopaedic intellects ever devoted to the public service of his country’.

Most people know Haldane today through the ‘Haldane principle’, which states that researchers are best placed to choose the subject of their state-funded research and is invoked whenever scientists wish to keep ministers at arm’s length. But this is only a fragment of a much wider philosophy of government. Let me offer five other Haldanean principles that could guide political parties of any persuasion today.

First, change must be principled, holistic and dramatic. Lasting progress requires deep preliminary thought followed by decisive execution.

As Secretary of State for War, Haldane undertook a wholesale reconstruction of Britain’s military and intelligence structures, guided by a single vision: that every part of the army should exist to win wars. Over six years he transformed the post-Boer War army – then manifestly unfit for purpose. He created the British Expeditionary Force of 160,000 highly trained men whose rapid mobilisation helped halt the German advance at the gates of Paris. He established the Territorial Army, the Officers’ Training Corps, the Special Reserve and the Imperial General Staff. He chaired the committees that led to the creation of the RAF and the Secret Service Bureau – the forerunner of MI5 and MI6. His successor at the War Office, J.E.B. Seely, later wrote that these reforms ‘saved the state’. The Ministry of Defence today requires a similarly holistic reassessment of purpose and capability – one that revives Haldane’s conception of a ‘Nation in Arms’ and works across government to renew public service.

Second, education is a core national resource. Schooling was pitifully under-developed in 1916, with only 10 per cent of young people remaining in school beyond the age of 14. Haldane never held ministerial office in education, but the pursuit of better education permeated his whole life’s work. No one did more to lay the foundations of the modern British university system.

He co-founded Imperial College and the London School of Economics, transformed London University from an examining body into a teaching institution and shaped the modern Welsh and Irish university systems. He enabled the rise of the great civic universities – Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield and Bristol – all established before the first world war. He founded the British Institute of Adult Education in 1921, championed continuation schools and promoted workers’ education throughout their lives. Continuous learning – and the intelligent deployment of AI in education – would undoubtedly sit at the heart of his thinking today. Education, at every age and level, was his abiding cause.

Third, progress depends on cross-party co-operation. What distinguished Haldane from many reformers was his instinct for working across party lines. His era was bitterly polarised, and the passage of the Parliament Act in 1911 was anything but consensual. Yet Haldane understood that durable reform required broad involvement in the decisions being made. Some of his most important educational work was done in close co-operation with Conservatives such as A.J. Balfour. When the Conservatives later found themselves in opposition, they supported his army reforms. He joined Labour’s first government not out of ideological conversion, but because it seemed more serious about educational reform than the Liberal party.

Fourth, effective government requires a professional civil service. Haldane believed administration to be both a science and an art – and one that could be taught.

He chaired the 1918 Machinery of Government Committee, producing a blueprint for the modern state: clarifying departmental responsibilities, improving co-ordination and professionalising the civil service. In 1922 he founded the Royal Institute of Public Administration as a centre of excellence for public service. His belief in professional management led him in 1906 to establish an army class at LSE to teach administrative skills to officers – the origin of Britain’s business school movement.

Fifth, and finally, democracy must be embraced. Haldane believed decisions should be taken as close as possible to those affected, subject only to efficiency. Power should move upwards only when it demonstrably improves outcomes – while preserving the individual’s stake in political choices made beyond their immediate control.

Applied today, this principle offers a framework for regional devolution. Haldane trusted the electorate, travelled the country to defend controversial reforms and spoke to his mining constituents about Einstein’s theory of relativity without condescension. He would not have tolerated today’s gulf between policy and popular consent. Haldane believed that there was an underlying ‘general will’ of society, often very different from short-term public opinion.

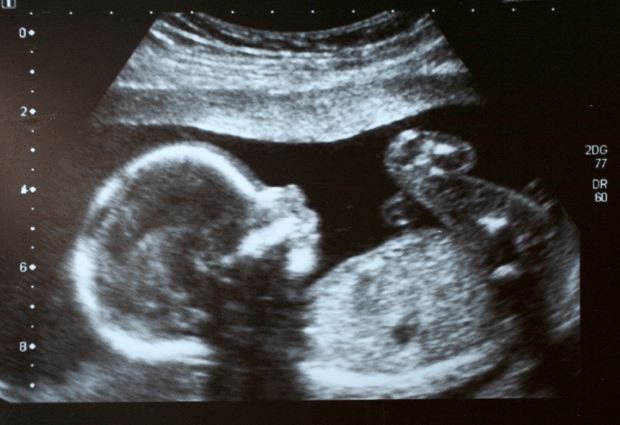

Haldane was a formidable figure physically as well as intellectually. Diabetically rotund before the advent of insulin, he nevertheless had the stamina to walk from London to Brighton. When Winston Churchill once prodded his stomach in the Commons and asked ‘What’s in there, Haldane?’, he replied: ‘If it is a boy, I shall call him John. If it is a girl, Mary. But if it is only wind, I shall call it Winston.’

The joviality points to a serious truth: the difference between substance and style. Great speeches are not enough. Real change requires a lifetime of thought. Haldane once proposed that the words ‘It costs nothing to think’ be written in gold on the walls of the War Office. That remains his most valuable lesson.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.