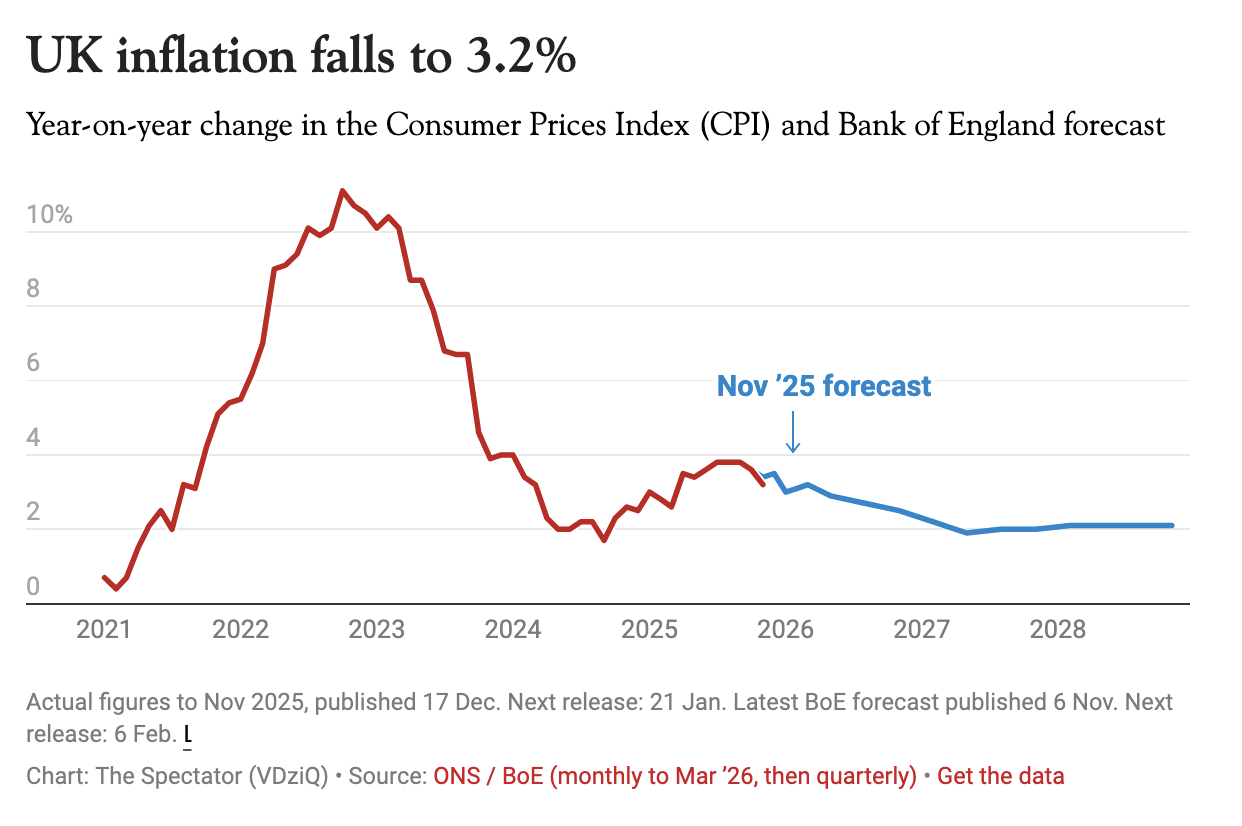

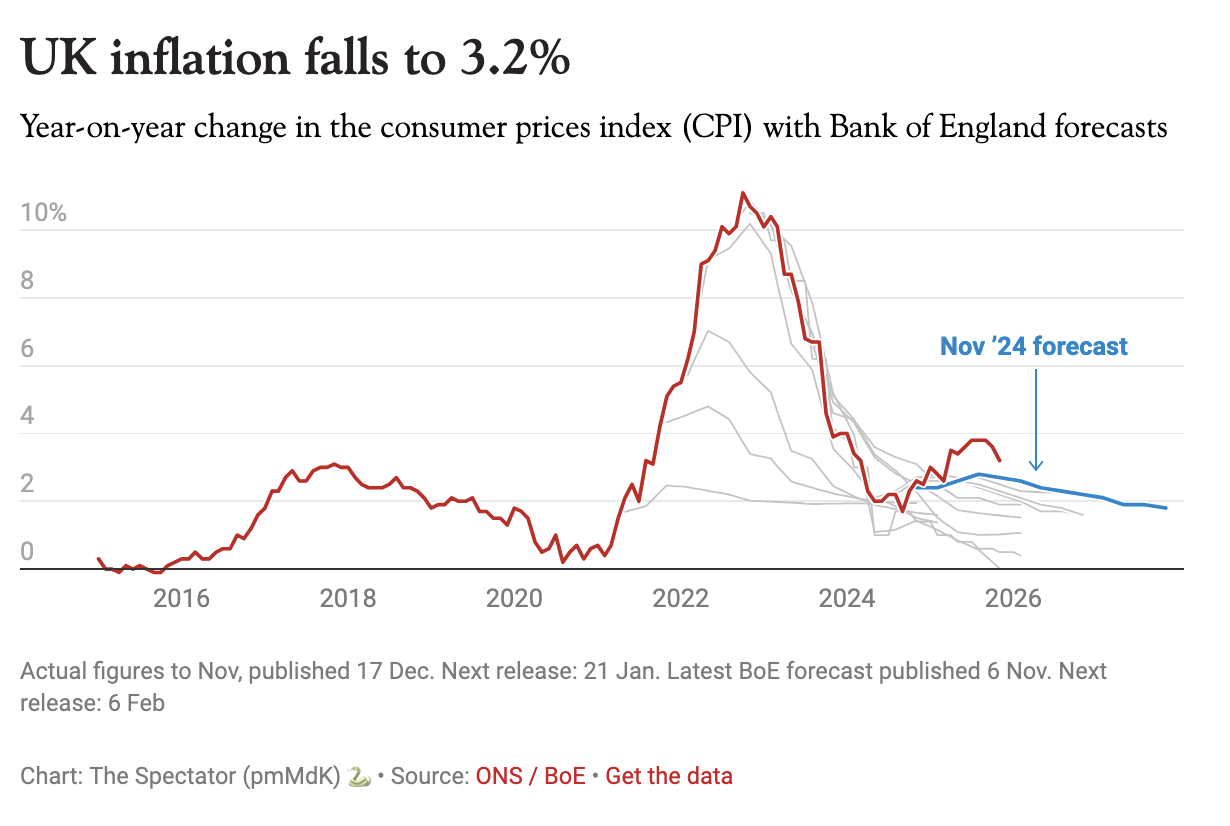

For the second month in a row, inflation has fallen. Figures released by the Office for National Statistics show that last month the Consumer Price Index fell to 3.2 per cent from 3.6 per cent in October. November’s reduction is the largest since September 2024.

Figures from 2020

Figures from 2015

For the government, this is very good news. High inflation over the past six months has intensified pressure on Labour to tackle the cost-of-living crisis. This was clearly reflected in last month’s Autumn Budget, with Rachel Reeves announcing freezes to rail fares and fuel duty, as well as measures to lower household energy bills.

If inflation continues to decline at this rate, the Chancellor will claim victory. Whether or not this is credible is debatable. UK inflation is largely dictated by external factors outside of the government’s immediate control. The UK is not a large bloc, like the US or the EU, capable of influencing food prices. Energy prices are determined by the price of natural gas, which the UK cannot change. Even the domestic policy tool most effective in controlling inflation – the interest rate– is controlled by the Bank of England.

Still, there could be more reasons for the government to celebrate. Consecutive and large reductions in inflation back up the Bank of England’s prediction that inflation is past its peak and will return to its 2 per cent target in 2027. This is almost certain to ease any final concerns about inflation and allow the Bank to lower its interest rate tomorrow to tackle weak growth and rising unemployment. If a cut is made, the government’s borrowing costs will be lowered, giving it some much needed financial relief.

However, the inflation statistics released by the Office for National Statistics each month do not show the real impact on the cost-of-living crisis. The prices that matter most to consumers – food, energy, and transport – have been consistently rising for too long.

These relentless price hikes have become unbearable for many. Simon Hawking, CEO of Acts Trust, a charity tackling food poverty in Lincoln, noted that ‘we expected a return to normal after the pandemic, but we keep seeing demand for our services increase… prices that were painful two years ago are still painful today.’ Anita Rao, CEO of Wesley Hall Community Centre, a charity in Leicester, added that ‘high energy prices mean many of our clients are forced to wash their clothes by hand and for some we provide their only decent hot meal of the week.’

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be much light at the end of the tunnel. Last month, the Office for Budget Responsibility downgraded its prediction for real growth in household disposable income to near zero, meaning it is unlikely that family spending will return to normal any time soon. Slowing inflation may soften the blow, but it won’t mend many wounds.