Australia’s housing market has seen escalating prices since the 1970s.

Various ad hoc attempts to cheapen supply have been tried by variations of subsidy schemes to the less well-off and to first home buyers. The latest scheme is the federal government’s $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund, which features a home deposit guarantee scheme for first buyers and social and affordable housing programs. This has so far resulted in a planned 18,500 new homes, well short of the estimated 640,000 Australian households whose housing needs are said to be currently unmet.

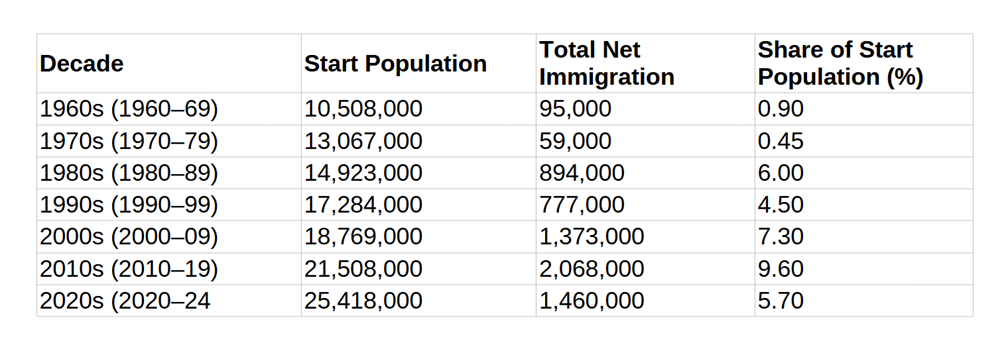

Many see the price escalation as being due to booming demand as a result of net immigration. Thus, research shows 34 per cent of people (72 per cent of One Nation supporters) ranked immigration in their top three factors responsible for the housing affordability problem. The increase in immigration is well-documented.

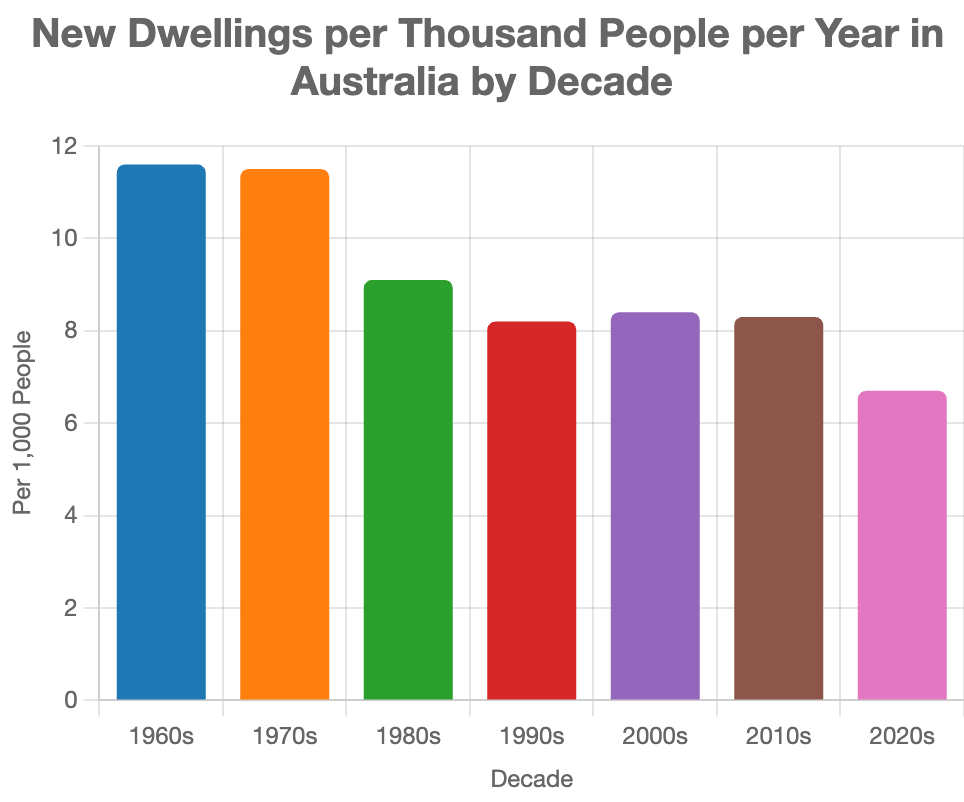

Immigration from Muslim and some African countries has certainly led to reduced social cohesion and increased crime, but immigration per se need not bring escalating housing costs if supply is allowed to increase. This has clearly not been the case in Australia where, according to Grok, new dwellings per thousand people has almost halved since the 1960s.

The inability to increase supply is not due to the cost of building new houses – construction of new houses has remained non-unionised and their inflation-adjusted cost has fallen.

The jammed valve on the pressure cooker preventing price relief is the urban planning regime that constrains land availability for housing development. Australia has more land per capita than almost anywhere else in the world, yet planning restraints on urban growth ensure that 90 per cent of us live in the 0.22 per cent of the land that is classed as urban. As a result, in real terms, the price of the average housing block has risen from about $100,000 in the 1960s to $525,000, in spite of the average size of a new block having been shrunk by a third.

The cost of the land component of a new house has risen to account for over 60 per cent of the total home price.

Australia cities stand-out among the 95 cities assessed by Demographia for housing affordability. All Australia’s mainland state capitals are among the 15 most costly.

Many US cities (Atlanta, Dallas Fort Worth, Houston) are experiencing high population growth with little pressure on house prices, which in relation to income levels are only one third of average house prices in Sydney. Invariably those cities have much less onerous planning restraints on new housing, particularly for developments at the city edge, than is found throughout Australia.

The tragic consequences of Australian planning restraints on house availability are readily evident. These started with Australian planning authorities adopting British models that were designed to ensure preservation of the countryside, where the urban area is 8 per cent of the total area – a far cry from the 0.2 per cent in Australia! These notions were built upon by others including a wish to see a more concentrated population for social and cultural reasons.

Regulatory inertia makes reversing the impacts of these policies difficult. Additional problems include the effect of a price fall on recent highly mortgaged buyers (especially new buyers under the government’s policy of allowing down payments of only 5 per cent).