What are the achievements of the Australian experiment in liberty? They must be clearly articulated in our dangerous world of negative ideas and geopolitical threats.

We need clarity and unity of purpose if we are to build on our historical success.

Australian political liberties were achieved at an early time, as the Colonial Secretary told the NSW Legislative Council in 1853:

‘The colonists have already had secured to them the full liberty of the press, complete religious equality, and an unimpeachable administration of justice. By this bill they will have full political liberty, with only such safeguards as are absolutely necessary while the colony remains a British dependency.’

But it was not just political liberty. Adam Lindsay Gordon wrote in 1866 about a generous approach to life, ‘kindness in another’s trouble,’:

‘Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone.

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.’

This meant something to Australians. Gordon is the only Australian writer commemorated at Westminster Abbey in London, in the company of Charles Dickens and Jane Austen.

Dickens spent his life making fun of hypocrites who say noble things but are base villains, but for him Australia was a place where the convict Abel Magwitch could partly overcome the horror of Britain’s criminal system and underclass.

Dickens did not hate ‘social injustice’, but hated the expression on the face of a large man beating a small boy, to paraphrase GK Chesterton.

Members of the NSW Legislative Council used the word ‘liberty’ at least 80 times while writing NSW’s first constitution for self-government in 1853: ‘civil liberty’, ‘political liberty’, ‘they lost their liberty – their free institutions’, and ‘a right to personal liberty…’

The British liberties they referred to were not just barren labels. The right not to be detained except by due legal process was promised in the Magna Carta in 1215, and an elected Parliament independent of the King developed from the Glorious Revolution of 1688. These things are absent in many countries today. People died to achieve them in Britain.

Three Australian colonial parliaments in the 1850s gave liberty and equality meaning by giving all men the vote and secret ballot. They later gave the vote to women, and the right to stand for Parliament, beginning in South Australia in 1894-5.

Parliaments applied such phrases to develop democracy, land reform, the pastoral and mining sectors, economic development, education, and health.

Because of our history, Australians are part of the 6.6 per cent of the world’s population living in a ‘full democracy’ with two in five people in the world living under despotism, according to The Economist index.

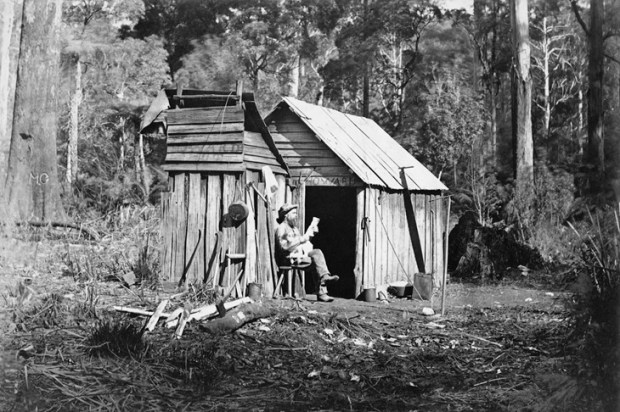

Settlers encountered problems we can hardly imagine while building an economy and democracy from nothing, including famine and disease. They faced major gaps in knowledge on every front. They struggled for self-government at a time when cabinet government was ‘imperfectly understood even in England, outside privileged circles’ as Jenks says. They had to survive without the ‘wrap-around services’ we now feel entitled to.

Adam Lindsay Gordon’s memorial at Westminster Abbey should be one of Australia’s places of pilgrimage in London, together with the memorial there to Admiral Arthur Phillip, the first Governor of New South Wales.

Some visit instead the grave of Karl Marx at Highgate Cemetery. But Australian colonial settlers did not conduct themselves on the basis of murderous ideologies, rather on what they saw as the facts and achievements of British history.

General phrases such as totalitarian, fascism, and communism have real meaning when you learn of the hundreds of millions who died in mass murder under such barren banners.

The Communist Manifesto provided useless boilerplate for violent and barren Eastern European governments well into the 20th Century.

The language we use is different. Does a budget or tax system sufficiently provide for liberty or equality?

Australian Parliaments debate such issues at length, and inconclusively, because they constantly return to the facts, revising and improving. They are not barren labels. Parliaments changed the balance between liberalism and illiberalism every decade up till today, mostly by improving.

Tribal warfare in our region and others today can be terrible and was in Australian history, for example. There was violence between settlers and Aborigines as pastoralists set up vast cattle and sheep ‘runs’ on hunting grounds.

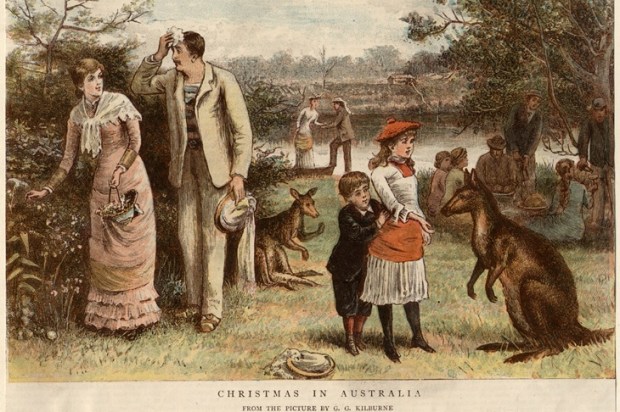

Pastoralists, together with their Aboriginal and European workers, began the Australian standard of living with the pastoral boom of the 1860s. We should find a better way to remember European and Aboriginal work and achievements. They lifted us out of poverty, together with the miners. Government programs now promote Aboriginal outback employment, with appropriate wages, and housing and drinking water.

Nearly all see Australia today as a place of opportunity and freedom, a refuge from hardship, and did so from the early 19th Century as settlers transformed our first colony from a prison colony. A few take all the advantages of Australia’s liberties while undermining them.

The leaders of our main political parties frequently say Australia ‘is the best country in the world’. Our history may in consequence be too, with its remarkable early democracy, without civil war, if you look at countries in our region, Europe, or just about anywhere.

Given our intellectual life this may be unknown to young people and migrants.

Perspective and proportion should not be lost as we endlessly debate our problems and try to rectify them. And we need to abandon entirely negative narratives.

Australia was not the heart of darkness, hallucinating in the heat, or the Ancient Mariner, adrift in the South Pacific, with ‘water, water everywhere but not a drop to drink’.

Government by organised crime is common in history and the world today.

But it has no dominion over today’s beneficial country, built on the liberties British settlers brought to our vast continent, and the hard work of generations of migrants given opportunities by those liberties.

Reg Hamilton, Adjunct Professor, School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University