A furore erupted recently over people jeering and booing during a Welcome to Country ceremony on Anzac Day in Melbourne. Although many in the media tried to caricature the protest solely as the work of alleged neo-Nazis, this is not the whole story. Ordinary people in the crowd also joined in.

Clearly, there is a growing sense of frustration – and even anger – in the Australian community over the issue. While I personally think it was disrespectful to the event for people to boo, I understand their deep sense of frustration. Showing respect goes both ways.

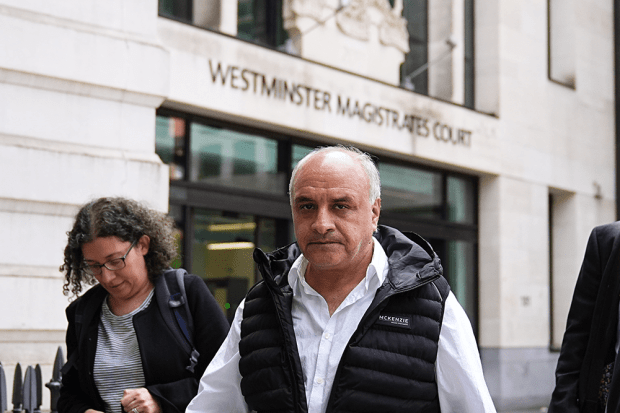

Sadly for the mainstream media’s narrative, one military veteran who was there spoke calmly and convincingly as to why a Welcome to Country on Anzac Day was not only itself disrespectful to those who had fought and died, but was also the reason many of his fellow veterans had chosen to stay away from the service. As Dr Stephen Chavura explains in a viral social media video:

Why are soldiers who fought for this country – and their descendants – being welcomed to this country as though it’s not their country? This is the big problem with the whole Welcome to Country ceremony being held at an Anzac service.

It’s being said to people who have fought for this country. It’s being said to their relatives who have made sacrifices for this country as well, all so they can be ‘welcomed’ to this country, probably by someone who has never fought for this country.

The whole idea of a Welcome to Country is about one tribe welcoming another tribe onto its land. By definition the other tribe does not belong on that land, doesn’t own that land. And that’s why the Welcome to Country is completely inappropriate in Australia, because it is essentially Indigenous Australians saying to Australians, ‘This is our land, it is not your land, and you are here as long as we want you here.’

Now this is bad enough, but it should absolutely never be taking place at an Anzac ceremony and it should never happen ever again.

I think Dr Chavura is completely right. Over the past couple of years, I have tried to do a deep-dive into the issue and what follows is a summary of what I have found.

How it all began…

First Nations political protocols of Welcome to Country (WtC) – delivered by an Indigenous Elder – and Acknowledgement of Country (AoC) – performed by a non-Indigenous host or chair of an event – are now ubiquitous throughout 21st Century Australian society. Anecdotally, I’ve spoken to friends who have to endure some form of ‘Welcome’ or ‘Acknowledgement’ several times every day as it is a required protocol at the start of every meeting. Not only is it counter-productive in terms of efficiency, but it has also been reduced to an empty tokenism.

The first ‘modern’ iteration of WtC was performed by Aboriginal Elder, Matilda House-Williams, on February 12, 2008, at Parliament House in Canberra. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd responded – with the support of Opposition leader, Brendan Nelson – by expressing hope that such Indigenous ceremonies might ‘become a permanent part of our ceremonial celebration of the Australian democracy’. Mark McKenna, from the Department of History at the University of Sydney, states:

The following morning, February 13, in a speech laced with the biblical language of remorse and atonement, Rudd delivered the long-awaited apology to members of the Stolen Generations, which he hoped would finally put an end to Australia ‘wrestling with [its] own soul’. In the months and years to come the national and international impact of the apology eclipsed the significance of the Welcome to Country rituals that had taken place the previous day, which, like the apology, represented the culmination of cultural and political changes nearly two decades in the making.

Now, with the exception of Western Australia and Victoria, all parliaments in Australia ‘make an Acknowledgement of Country at some time in the parliamentary year’. The practice has also been quickly adopted by many sporting clubs, businesses, schools and even religious institutions. Even many churches view these semi-religious-political practices as being compatible with Christianity.

‘Welcome to Country’ as Politically Progressive Phenomenon

Many argue that while WtC does contain some cultural ‘antecedents’ they are not what should be considered as being ‘strictly traditional’. Natsumi Penberthy outlines in The Australian Geographic the series of events which led to WtC’s more modern iteration:

Almost exactly 40 years ago these ceremonies first began to enter the Australian mainstream after a performance by West Australian Richard Walley and the Middar Theatre at the Perth International Arts Festival (which is on again for another few days) of 1976.

Richard and other performers with the Middar Aboriginal Theatre officially welcomed Maori and Cook Islander dancers who were refusing to perform without one on the lawns of The University of Western Australia during a multicultural dance performance. ‘I was surprised [by the request], but I didn’t mind,’ says Richard, a musician, dancer, writer, artist, and cultural educator.

After seeking permission from local Nyoongar Elders, Richard spoke the Welcome in the local tongue.

‘I asked the good spirits of my ancestors and the good spirits of the ancestors of the land to watch over us and keep our guests safe while they’re in our Country. And then I talked to the spirits of their ancestors, saying that we’re looking after them here and we will send them back to their Country.’ He followed it with a Nyoongar song about Country and then the Middar, which included TV personality Ernie Dingo, danced.

It is my view that this clearly demonstrates modern Indigenous protocols are a politically progressive phenomenon. That is, they serve a purpose other than what they were traditionally intended. Historically, it was to provide protection for outsiders – especially from other First Nation groups – as they travelled through a neighbouring land. Today though, they are about the promotion of land rights and cultural affirmation more generally.

WtC as Traditionally Practiced

While First Nations peoples practised a plethora of panentheistic beliefs, some form of ‘WtC’ seems to have been observed by most Indigenous groups. One of the best and most comprehensive studies on traditional Aboriginal culture and religion is The Arunta by Sir Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen. In a chapter entitled, Proceedings Attendant on Visiting Strange Camp, the authors make the following pertinent observation:

Visits are frequently made, either by individuals or by parties of men and women, to friendly groups of natives living in distant parts. If it be only one man who is paying a visit, he will often, in the first place, make a series of smokes so as to inform those to whose camp he is coming that someone is approaching, which, of course, is an indication of the fact that the visitor has no hostile intention, or he would carefully avoid making his presence known. Coming within sight of the camp, he does not at first go close up to it, but sits down in silence. Apparently, no one takes the slightest notice of him, and etiquette forbids him from moving without being invited to do so. After perhaps an hour or two one of the older men will walk over to him and quietly sit down on the ground beside the stranger. If the latter be the bearer of any message, or of any credentials, he will hand these over, and then perhaps the old man will embrace him and invite him to come into the camp, where he goes to the ‘ungunja’ (men’s camp) and joins the men. Very likely he may be provided with a temporary wife during his visit, who will, of course, belong to the special group with which it is lawful for him to have marital relations.

Crucial to understanding how a traditional First Nation’s ‘welcome’ functioned, is grasping the unique nature of Aboriginal ontology or worldview. This is because, as Elizabeth Dempster states, within a First Nation’s worldview, ‘Country is a relationship, a living system, not an object anterior to human society.’ What’s more, as Scherrer and Doohan further explain:

For Traditional Owners, asking permission from the cosmos and from other human beings – is a fundamental part of their culture, a deeply held obligation to care for and protect visitors to country by mediating between the phenomenological and the mundane domains of being in place to ensure safe passage. When unknown and uninvited people enter country, the Wanjina Wunggurr cosmological domain is offended and becomes unstable and potentially destructive… However, appropriate engagement with symbolic representations can rectify disorder in the world that might have been created – deliberately or inadvertently – and reinforce the order of the world.

Likewise, Deborah Bird Rose, a leading Australian anthropologist, further elaborates:

Countries, or the Dreamings in country, take notice of who is there. Country expects its people to maintain its integrity, and one of the roles of the owners is to introduce strangers to country. Trespass – use of country without permission or introduction – is a threat to the integrity of country, Dreamings, and owners. Bilinara people, for example, use the term kamariyu to refer to strangers, people who come from far away and must be introduced to the country by the owners. The ritual of introduction, which is by no means restricted to Bilinara people … includes the following steps: first, the owner brings the stranger to water, calling out to the country as he approaches; secondly, he or she wets the stranger’s head or arm and gives them water to drink.

Michael Murphy argues that the profound religious nature of an Indigenous ‘welcome’ ceremony also relates to the acknowledgement of ‘elders, past, present, and emerging’. Unlike remembering European ancestors – such as those killed in battle – recognising Indigenous Elders brings a person into the metaphysical worldview of the ‘dreaming’. Much like many people today from Asian backgrounds continue to practice ancestor worship. As Murphy explains:

Armed with an understanding of the Australian Aboriginal religious tradition, this constitutes a moment of liturgy, or ritualised, public prayer. Embodied in the description of the elders in this phrase is the acknowledgment of the continual Dreaming and the primacy of ownership of those storied by the elders as the auctoritas.

Murphy rightly goes on to conclude that, ‘it becomes apparent that when participating in a contemporary Welcome to Country those who are present enter into a public prayer which reverences the Aboriginal ontological understanding of Country’. According to Murphy, this is because of three foundational Indigenous religious truths:

- Through the continuation of the Dreaming narrative, Indigenous people practice their religion’s intrinsic metaphysic, linked to the land both spatially and temporally.

- Aboriginals of different nations fundamentally respect and understand the religious traditions of other nations when historically engaging in a Welcome to Country.

- The Elders are the custodians or magisterium of the sacred tradition.

Just exactly what this looked like in practice historically though, is in current scholarship and popular writings seldom defined.

WtC as Political Tokenism

As some have pointed out though, First Nations ceremonies today suffer from being reduced to tokenism. For example, the Aboriginal scholar Victor Hart, views both Welcome and Acknowledgment ceremonies as tokenistic because they re-present an ‘iteration of terra nullius mythology where blackfellas can appear at the beginning of the event (i.e. the beginning of history) and then conveniently disappear’.

Following on from this, others have viewed their performance as a politically correct form of cultural appropriation. This is because it affirms the reality of Indigenous connection to the Land, while avoiding any concrete application in the form of reparations or a treaty. As anthropologist, Kristina Everett, persuasively argues:

The kind of recognition these ceremonies gain from the officials who now request them is a token kind of recognition, quite unlike that at stake in a land claim in court. This is a benign if not patronising inclusion of Aboriginality in state celebrations and rituals. In other words, it is a way in which an idea of Aboriginal country can be included in state representations without legal or political consequences. It is a way for a claim to more friendly, more inclusive relations with Aboriginal peoples to be incorporated into the national story. It is also … a way for Indigenous claims to primordial connections to the land, which cannot otherwise be claimed by the Australian nation state, to be included in state ceremonies.

Significantly, the argument that Indigenous protocols are ‘tokenistic’ has been sometimes been used ‘positively’ by a few First Nations people. For example, in responding to the decision of former premier of Victoria, Ted Baillieu’s, decision to make WtC and AoC protocols non-compulsory for government ministers, the Indigenous writer Luke Pearson, commented:

These politicians do not respect Aboriginal people anywhere in Australia, or the millions of Australians who believe that this tiny gesture is not only essential, but nowhere near enough. It is a TOKEN gesture. It is meant to be a symbol of respect and understanding.

There is an obvious level of superficiality in all modern First Nation ‘welcomes’ in that the ceremony has to be extended and cannot be refused. In this sense, the question could legitimately be asked, is it really a ‘welcome’ at all. If an invitation cannot be declined then it is forced and even functions as a new form of colonialisation. As anthropologist, Emma Kowal, persuasively argues:

The neutered statement of Indigenous ownership that a WTC represents means non-Indigenous people can enjoy Indigenous culture and presence without feeling threatened by Indigenous sovereignty. This might explain why WTCs are most common in urban Australia, where native title claims are both unsettling to non-Indigenous Australians and most unlikely to succeed. The claims of Indigenous ownership made in a WTC are usually wholly symbolic with little chance of achieving legal reality.

WtC as Religious Totemism

The religious beliefs of First Nation’s peoples involve a complicated matrix of people, things and especially spiritual beings. For instance, Australian academics, Pascal Scherrer and Kim Doohan state:

The Traditional Owner’s notion of country is a tenure-blind view based on belonging and responsibility (according to ancestral relationship and Aboriginal Law) and a seamless integration of land, sea and air, as well as those human and non-human elements that sustain the country.

Scherrer and Doohan further explain the continuing socio-religious practice of First Nation’s people in northwest Australia as follows:

The seeking and granting of permission to access is a fundamental aspect of Kimberly Aboriginal people’s culture and is embedded in the more esoteric tradition of the Wunan, aspects of which deal with the establishment and maintenance of reciprocal relationships (both secular and sacred). It is thus an important cultural expression that forms part of the overall Indigenous governance system of local Aboriginal peoples, and non-Aboriginal visitors becomes a part of this system by their mere presence in country.

Scherrer and Doohan further explain, ‘The term Wunan refers to a trade route that embodies a structured network of social, economic and ritual relations.’ All of which is to say, the traditional ‘Welcome to Country’ of First Nation’s people were (and continue to be) a clear and unambiguous, socio-religious act. This is especially seen though, in the use of WTC ceremonies. As Emma Kowal explains:

A WTC can also be thought of an as continuous Aboriginal tradition. In a WTC, he sees elements of the classical rituals performed on ‘those unfamiliar with and to the particular tract of country – rubbing on under arm sweat, spraying water into lagoons, calling out to ancestral spirits, speaking in the language of that country – not so much to welcome strangers but to protect them from possible harm from the unfamiliar spirits of the country.

Likewise, Alessandro Pelizzon and Jade Kennedy helpfully explain:

The metaphysics of the Dreaming shape and determine Aboriginal concepts of Country and must be considered as always present within the act of Welcoming someone to one’s Country. Indeed, the reference to mythical ancestors contained in a number of Welcome to Country events is revealing of metaphysical implications that are rarely if ever further explored or contextualised.

Ian Clark provocatively argues that by participating in a First Nations ‘welcome’ the non-Aboriginal person is ‘Aboriginalised’ through the performance of the act. As Pelizzon and Kennedy rightly argue, ‘The ‘other is culturally situated in relation to Country and therefore incorporated within an Aboriginal system of reciprocity and exchange.’

The Rise of Religious Syncretism

The Anglican Cathedral in Melbourne has permanently installed an artwork showcasing First Nation’s spiritual totems as a way of promoting a permanent WtC. Rather than display the more customary prescribed set of words, the Cathedral has six glass panels depicting the panentheistic creation stories of the Kulin people. What’s more, they are strategically placed so that worshippers are confronted with its message immediately upon their entry into the building. According to Andreas Loewe, the Cathedral Dean:

The panels also include an image of the wedge-tailed eagle Bundjil, the creator spirit for the Kulin people. It [Bundjil] is able to speak and talk and interact and exchange.

In my view, this is a clear example of religious syncretism where the Bundjil spirit of the Kulin people is viewed as an active spiritual being to be worshipped alongside the God of the Bible. Significantly, traditional Indigenous ‘welcomes’ never involved the installation of a permanent work of art, let alone the physical representation of totems, as such sacred items were universally viewed as being taboo to all but the specially initiated.

Most conservative Christians will immediately understand the theological problem with a politically progressive art installation – in an Anglican Cathedral no less – promoting Aboriginal pantheism alongside Biblical spirituality. Both the Old and New Testament proclaim an exclusive message of there being one true God (Psalm 18:31-50; Isaiah 46:9-11), that Jesus Christ is the only way to God (i.e. John 14:6; Acts 4:12) and hence, all other religious beliefs and practices are forms of idolatry (Romans 1:18-25). The syncretistic merging of Indigenous beliefs with Biblical religion then, are clearly incompatible.

This is because First Nation’s spirituality is inherently panentheistic and thus, antithetical to reformed-evangelical Christianity. This is because the Bible reveals God as being transcendent – distinct from what He has made – as well as being immanent – in personal relationship with His creatures. What’s more, the Bible also teaches that He alone made and sustains the world (i.e. Hebrews 1:1-3).

Time to Say Goodbye to Indigenous Welcomes

Ultimately, I think it’s time we said ‘goodbye’ to both Acknowledge of and Welcome to Country ceremonies. They are empty cultural, religious and political expressions which achieve nothing but division within our nation.

Welcomes are really only meaningful when they can be both extended or withdrawn. After the failed Voice campaign, Marcia Langdon suggested that we wouldn’t receive an Indigenous ‘welcome’ ever again. More and more people are thinking, if only that were really so.