‘Green hydrogen is not dead,’ insisted Chris Bowen, Australia’s benighted Minister for Energy and Climate Change as the news broke last week that iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest had abandoned his quixotic quest to produce 15 million tonnes a year of the fuel by 2030.

Only a year ago, Forrest claimed that ‘Anyone, including Elon (Musk), including, you know, whoever you like, who says hydrogen hasn’t got a massive future, are muppets.’

But Forrest was looking more muppet than mogul as he announced last week that he was ‘postponing’ his hydrogen targets to an unspecified date in the future.

Abandoning the 2030 target must have been disappointing for Forrest who has been living the green dream but it was even more harsh for the 700 workers he sacked.

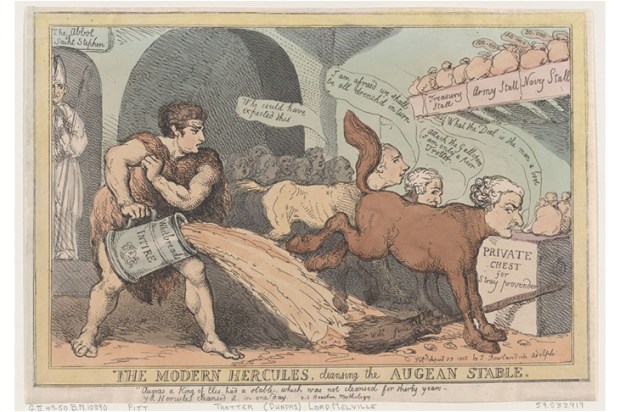

None of this daunted Mr Bowen. ‘Reports of the death of the green hydrogen industry are greatly exaggerated,’ he quipped, trying to channel Mark Twain. Instead he sounded more like the pet shop owner trying to convince John Cleese that the parrot he had just bought and which turned out to be nailed to its perch was not dead, just ‘pining for the fjords’.

It is only five months since both the Albanese federal government and Cook Labor government in Western Australia announced a $140 million agreement to build a Hydrogen Hub in the Pilbara desert with ‘the potential to become an international gateway to Australian-made green steel and iron’. The hub is supposed to support around a thousand direct and indirect jobs and is meant to become operational in 2028. According to the breathless media release, the ‘planned pipeline could enable hydrogen production of around 492,000 tonnes per year – enough to decarbonise existing ammonia production on the Burrup Peninsula’.

Mr Bowen is still saying there is at least $200 billion of investment in the green hydrogen pipeline. Perhaps. But how much will move from the pipeline to production? A survey published by the Boston Consulting Group last year gives a clue. It found that of 824 green hydrogen projects ‘in the pipeline’ in North America and Europe, with a theoretical capacity to produce 21 million tonnes of green hydrogen a year, only 2 per cent had progressed to the planning stage, and only 0.2 per cent had been completed.

Green hydrogen is never going to be made in Australia under the current conditions because it requires massive quantities of cheap, renewable energy and there is no such thing as cheap, abundant renewable energy in Australia.

Even Labor is being forced to admit as much. Finance Minister Katy Gallagher conceded this week that the new Australian Energy Market Operator report provided undeniable evidence of the low levels of wind and solar generation. That’s quite an admission when you consider the billions that have been poured into these intermittent, weather-dependent sources of power.

The recognition that wind and solar power are not sufficient to power Australia has forced Gallagher, at least, if not others in the federal government to turn to gas as a ‘transition’ fuel on the road to the net zero nirvana. Calling gas a ‘transition’ fuel used to be a Labor orthodoxy a generation ago but the adjective was banished during the heady days of the government-subsidised renewable gold rush.

All of a sudden Gallagher is claiming that Labor has a gas strategy ‘which is all about making sure that we do have enough domestic gas to make sure that we… have that option of the firming when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow, that we’re able to make sure that we’ve got the right energy mix. And you know, this is where I think the government’s navigating straight down the middle. We’re not – you know – pretending that you can just switch to renewables.’ Who is she trying to kid?

Only a fortnight ago, Labor created a green-ratings system that deliberately discourages investment in gas by refusing to classify it as a ‘sustainable’ investment under its draft ‘sustainable finance taxonomy’. Instead, gas has been classified as a ‘phase down’ sector in the consultation report produced for Treasurer Jim Chalmers by the Australian Sustainable Finance Institute, which was tasked with driving ‘capital into activities that will decarbonise the economy at the speed and scale required to reach our global climate goals’.

If Labor implements this economy-destroying scheme the only place it will drive investment in gas is off a cliff. What it represents is a death sentence – capital punishment – for one of Australia’s most important sources of energy and export dollars.

Yet the Australian government is, of course, not alone in this project of self-sabotage. Its sustainable financial taxonomy is just a slightly more longwinded way of achieving what the newly-elected Labour minister for Energy Security and Net Zero in the UK, Ed Miliband, has promised to do when he announced, in line with his stated policy set out before the election, that he would grant no new licences for North Sea oil and gas exploration. Given that the UK relies on fossil fuels for 75 per cent of its energy all that a ban on gas and oil all will achieve is increase its imports of those products.

At least the British Labour government is committed to the expansion of its nuclear power industry which is more than can be said for Australia’s government. Ms Gallagher’s newfound discovery that wind and solar power are not up to the task of providing baseload power still prompted her to say that any debate about nuclear energy was ‘a distraction’ and the idea that ‘small modular nuclear reactors are going to be able to be deployed is probably pretty fanciful at the moment’. In the real world, nuclear power, whether it is generated in small modular or conventional reactors, is not nearly as fanciful as green hydrogen.

The reality that Labor is unable to acknowledge is that even in countries where low emission energy is vastly cheaper than in Australia because they have abundant hydro power – think Norway – and/or nuclear energy – think France – green hydrogen is not commercially viable. The Norwegian producer of hydro electricity, for example, announced last month that it was shelving its green hydrogen plans because it had ‘underestimated the challenges’ in developing green hydrogen which had become much more expensive than they had expected. French energy generator, Engie, has also shelved its green hydrogen plans, and the European Union’s 2030 target of 10 million tonnes per annum has been criticised by its auditors as ‘over ambitious’.

Mr Bowen is fond of mocking the use of nuclear energy in Australia saying that it is ‘a fantasy wrapped in a delusion accompanied by a pipe dream’. In reality, it is green hydrogen that is the fantasy; someone needs to tell Mr Bowen he’s dreaming.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.