Our political elite are to blame for our educational malaise, not our educators…

At the start of another academic year, a quick survey of the educational scene is in order. Unsurprisingly, as anyone who’s taken even a cursory glance at our schools will note, the results are grim. Along with our slide down the PISA scales, there are plans to reform NAPLAN, install tutors in classrooms, and abolish the ATAR. All of this occurs alongside the sobering realisation that for all our increases in technology and funding, little has been achieved in tangible results.

In fact, we’ve gone backwards. As the latest PISA results show, over the last two decades Australia has slipped from being a top-ten performer to a country that fails to ‘exceed the OECD average in one of the assessment domains’. We’ve dropped ‘from fourth to 16th in reading, eighth to 17th in science and 11th to 29th in maths’. Even the commercial media are talking about a ‘crisis in education’.

Who’s to blame then? That’s easy: teachers. Across the political divide, there has been a unanimous answer to our educational malaise: we lack quality teachers. As piece after piece after piece has pointed out, improving teacher quality is the easiest way to lift educational outcomes and productivity.

It’s no surprise then that figures like Victoria’s Shadow Minister for Education, Matthew Bach, have waded into these murky old waters. Writing in The Australian and Spectator Australia, he cites a Productivity Commission report summarising the prevailing wisdom by stating, ‘…the largest single factor in student success, and their ability to go on and make a meaningful economic contribution, is teacher quality.’

Cue then the usual easy answers to what has been an intractable problem. Per Bach et al, what’s needed are relevant reforms: something inclusive of a higher ATAR entrance and a training regime with ‘meaningful and rigorous systems of teacher appraisal’. Simply put, hire brighter teachers and give them the right tools and training, and decades of decline will vanish overnight.

This is clearly not the response we require. In part, it’s impractical and tautological. In any field of endeavour, having higher-quality practitioners will lead to better results. Better chefs will improve our restaurants; better builders our houses. And dare I say it, better politicians will improve our politics. If Canberra expects a Montessori in every classroom, are we not entitled to a Metternich in return? Speaking as a qualified teacher, I can confirm that – like all jobs – our teachers reflect the usual range of abilities and intelligence. And that the majority carry out their roles with aplomb.

Yet this is not the primary problem. While there is some truth to the remarks that teachers have a part to play, it is my opinion that their main function is to obfuscate. The goal is to shift our social failures onto teachers and away from politicians. It’s a cynical ploy designed to exculpate the political class for their vast errors and offer up teachers in return. It appears to have become little more than a vanity project in which the innumerable problems now afflicting education and the economy can be alleviated with a sole teacher-led silver bullet.

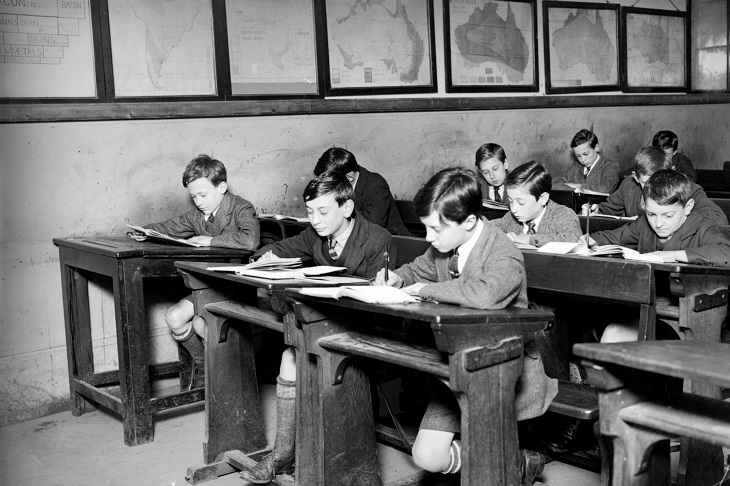

As those really responsible for our decline are our elite and not our educators. A notion that is evident with even the most basic logic. For one, we already have a generation that has spent much more time in education than their predecessors – with more of us earning a degree than ever – for far inferior results. How do we square the circle that prior teachers – with their one year ‘dip-eds’ – spent far less time in training for far superior results?

Primarily, what recommendations such as Bach’s ignore is the decline in the social context in which teaching takes place. As like many such articles, little mention is made of the vast socio-cultural changes that have taken place and within which schools now operate.

The most obvious is our diversity. As is often noted, Australia is one of the most diverse societies in the world. Something that is not unrelated to our educational decline. As unfortunately for the cosmopolitans, per Pisa, the most successful education systems tend to be found in places of profound homogeneity. Aside from Singapore, the best-performing systems are in traditionalist locales like East Asia and Eastern Europe – and not the liberal West.

The negative effects of diversity are also witnessed within countries. As American author and educator Freddie de Boer has noted, there are a large and persistent gaps in educational attainment between different groups – and of which teachers can do little.

Related to this is the issue of classroom management. A notion that is the sine qua non of teaching and without with no learning can take place. This is something that continually successful systems such as Japan take for granted, yet it’s an area in which Australia performs particularly badly.

As a recent article in The Australian observed, our educators are now on the front lines of ‘classroom war zones’. A trend that has led to staff shortages as teachers leave the profession in droves as they are ‘stabbed…kicked…[and] bitten’. As the OECD confirms ‘Australian classrooms are among the least disciplined in the world’ with a third of surveyed students reporting that ‘the teacher has to wait a long time for students to quieten down’ and that ‘students don’t listen’.

This is not to mention even more extreme cases. Aside from ill-discipline and poor behaviour, pupils are now permitted religiously-sanctioned weapons, students are stabbed in schools, and schoolboys are killed in gang riots. On top of this are the increasing number of students with some form of learning disability such as ADHD or autism.

The state of the family is another concern. Even in schools of relative success and stability, many children are now attending without the support of a stay-at-home mum or traditional two-parent family. A trend that’s predictive of an assortment of negative outcomes and that starts from the earliest years of education. As American author Mary Eberstadt has observed, more time in child care and away from parents correlates with maladies such as sickness, disobedience, and aggression.

These are trends that are evident in Australia too. Despite the desires of our politicians, the farming out of infants to the State is not in their best interests or ours. Most importantly, even the much-touted economic calculus doesn’t add up. As Virginia Tapscott recently noted in The Australian:

Even the economic rationale of childcare has been called into question. While group care is the cheaper option in the short term due to a high carer to child ratio, the likes of Peter Cook, an Australian family psychiatrist, and Jay Belsky, a researcher with the University of California, have long argued that the consequences of childcare make it more expensive than parent care in the long run.

As like much economic thinking, it fails to consider non-economic criteria. In essence, many of the benefits of childcare are illusory. As Tapscott, citing the Australian psychiatrist Peter Cook, states: ‘Generous parental leave and caregiver support … would actually cost less than the consequences of parental absence.’

That’s right: it’s cheaper (and better) in the long run for parents to actually parent their children than to hand them off to strangers and the State. Childcare is thus a false economy. Like cheap wine or junk food, it’s something that appears to be a ‘financial saving at the outset but ends up leading to greater expenditure’.

All of which is related to our broader subordination of education to economics. Witness the state of our universities, for example. Now dominated by (full fee-paying) foreign students, tertiary education in Australia has become a farce: with worries by academics about the decline in literacy, numeracy, and academic standards ignored by administrators only concerned about the bottom line.

An explicit focus on teachers (and teaching) also ignores the main social trends taking place and against which teachers are essentially impotent. Book reading is down. Screen time is up. As is the continued dominance of America-led liberalism and its vulgar tendencies: like Hollywood, fast-food, and the coarseness and crudity it promotes. An ‘Empire of Lies’, as some have called it.

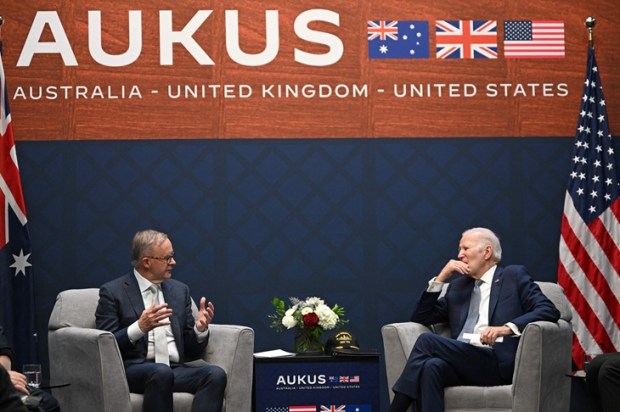

So by all means, train our teachers as well as we can. But don’t use them as a scapegoats for an elite-led social failure. It’s the political class who are to blame for our malaise, not our educators. It’s they who’ve changed the character of our schools and suburbs. It’s they who’ve reduced education to a business. It’s they who’ve helped eviscerate the family. It’s they who’ve overseen the deterioration in reading and culture. They are to blame for our decline, not our teachers.