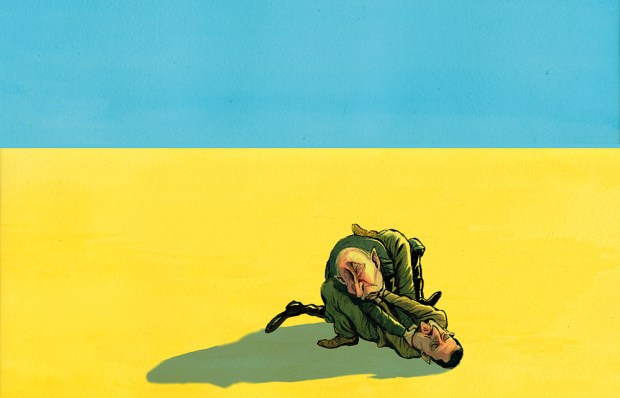

Two of Ukraine’s most famous ballet dancers face dismissal, cancellation and possible mobilisation into the army. Their crime? They dared to dance a segment of Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake during a European tour.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Culture slammed Serhiy Kryvokon and Natalia Matsak’s performance as ‘promoting the cultural product of the aggressor state’. The National Opera of Ukraine cancelled Kryvokon’s next scheduled performance – as well as his exemption from compulsory military service and permission to travel. If the dancer returns to his homeland, he will not be able to leave again. As a result, both Kryvokon and his prima ballerina wife Matsak find themselves in limbo: cancelled in their native Ukraine despite being among the most prominent artists who have stayed in Kyiv to perform throughout the war.

Since Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion, all forms of Russian culture – including music and literature – have been excluded from the repertoires of Ukrainian theatres and concert halls and purged from the curricula and bookshelves of schools and universities. ‘We have completely removed works by Russian composers since the start of the full-scale invasion,’ says National Opera director Petro Chupryna. Kryvokon and Matsak’s performance’s ‘violated [our] corporate ethics and norms and the collective decision not to participate in performances by Russian authors’.

At the core of Ukrainian nationalists’ rush to cancel Russian culture and language lies a fundamentally Putinist assumption that the classical works of literature and music, as well as the Russian language itself, belong to the Kremlin. They emphatically do not. Putin is neither the master nor even the inheritor of Russia’s great artistic tradition.

‘Tchaikovsky’s works are not part of Russian culture, they are part of world culture,’ says Matsak, speaking from Austria where she and her husband have been left stranded by the scandal. ‘It belongs to us too.’

The Putin regime, like the Soviet one that preceded it, has regularly attempted to appropriate masterworks of Russian art to build a narrative of national greatness. But the morally sophisticated response is not to cede ownership of Russian culture to the Kremlin, but rather to take it away. BBC Radio made this point eloquently in 1940 when it chose the music of Richard Wagner as a major component of its classical music programming for the summer of that wartime year. As German bombs fell on London, Britons sheltering underground listened to Wagner on their radios. The BBC’s implicit message was very clear: Wagner does not belong to you, Mr Hitler.

Ironically, Swan Lake itself is a perfect example of how a famous work of 19th-century music and choreography can be the object of two opposite narratives. For Soviet state TV programmers, Swan Lake was the ultimate symbol of safe, reassuring regime art – which is why a video of the ballet was played on repeat during an August 1991 coup attempt by hardliners against Mikhail Gorbachev. But to Russia’s democrats, Swan Lake became a code for the twilight of the old regime. ‘In 1991, Swan Lake became a symbol of the fall of the Soviet Empire,’ says Matsak. ‘Perhaps this ballet should be performed more often, as a reminder of the end of every empire of evil.’

In occupied eastern Ukraine, Russian authorities have purged libraries of Ukrainian-language books and demolished statues of Ukrainian national heroes, such as poet Taras Shevchenko. But that is hardly an argument for Ukrainians doing the same in reverse on their side of the border. Both attempts to destroy and deny culture are equally barbarous. Ukrainian ultranationalism, with its desire to erase all traces of Russia and Ukraine’s shared cultural heritage, is just Putinism in the mirror.

Nationalists protestors have demanded that even monuments to great writers born in Kyiv, such as Mikhail Bulgakov and Anna Akhmatova, be removed on the grounds that they wrote in Russian rather than Ukrainian. In Odessa, a majority Russian-speaking city, a nationalist campaign is also under way to remove the landmark monument to the Empress Catherine the Great, the great port city’s founder who did not have a drop of Russian blood. But the narrative of rejecting and cancelling everything Russian only plays into Putin’s hands. The presumption that Russian-speakers are not true Ukrainians is a fundamentally Putinist world view. It suggests that the hundreds of thousands of Russian speakers who have fought and died for Ukraine’s freedom in the face of Russian aggression are not fully members of the Ukrainian nation.

The sophisticated response is not to cede ownership of Russian culture to the Kremlin, but to take it away

That’s not only wrong and obnoxious but also deeply divisive. It’s poison in the root of Ukraine’s future, since by the Ukrainian government’s own statistics Russian is spoken at home by more than half of Ukrainian schoolchildren (not including the occupied territories). Indeed in February last year the reason officially given by the Rada, Ukraine’s parliament, for refusing to add Russian to an EU-mandated list of protected minority languages was that Russian was the majority language of Ukraine. It was Ukrainian, as a minority language, that needed protection and promotion, the Rada insisted.

Plenty of countries adopt, co-opt and absorb in part or in full the language of their former colonial masters. The US successfully took over their inherited English culture and language and made it distinctively their own. So did Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Ukrainian Russian has its own inflections, flavour and vocabulary, as the brilliant 19th-century Ukrainian-born satirist Nikolai Gogol proved.

At base, cancelling all things Russian weakens Ukraine and strengthens the Putin regime. In the first months of Russia’s full-scale invasion, tours and visas by Russian performers were cancelled all round the world. Ukrainian performers could have moved in and filled that cultural space, taking Russian culture out of the Kremlin’s hands in the most literal way. But instead ‘our internal quarrels and moralising effectively open doors for Russians to return to the world stage’, says Matsak. A staunch refusal to perform in any Russian-created ballet ‘closes Ukrainians’ access to communication with Europeans in the language of art familiar to them’.

Matsak’s cancellation is especially ironic because the main piece in her European tour was a new ballet based on the 1914 Ukrainian melody ‘Shchedryk’ – known as the ‘Carol of the Bells’. Swan Lake took second billing to an important new piece of modern Ukrainian music and dance. But in truth neither ‘Shchedryk’ nor Swan Lake belong to a nation, much less to any regime or leader, but rather to all civilised people in the world.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.